The Conquest of Death

The Conquest of Death

Violence and the Birth of the Modern English State

Matthew Lockwood

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven & London

Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College, and from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2017 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Bulmer type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016958014

ISBN 978-0-300-21706-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my parents, Jack and Nancy

Contents

Acknowledgments

THE PROCESS OF RESEARCHING AND writing a book would be impossible, or at least far more difficult and much less enjoyable, without the help of numerous people. I would like to thank my colleagues at Yale University and the University of Warwick for their welcoming collegiality and enthusiastic support. Particular thanks are due to Amanda Behm, William Bulman, Christian Burset, Mara Caden, Haydon Cherry, Megan Cherry, Leslie Cooles, Justin du Rivage, Carlos Eire, Paul Griffiths, Steve Gunn, Elizabeth Herman, Rab Houston, Richard Huzzey, Emma Kaufman, John Merriman, Jamie Miller, Sara Miller, Noah Millstone, Wendy Moffat, Ariel Ron, Dave Tengwall, Courtney Thomas, Matthew Underwood, Jennifer Wellington, and Alice Wolfram, for advice, encouragement, and many productive and stimulating discussions.

Steve Hindle and Bruce Gordon read much of what follows with careful eyes and open minds. I will be profoundly proud if my work reflects their incisive and insightful comments and suggestions. Special thanks are owed to Keith Wrightson, who not only read and commented on the entire work in its various stages and iterations, but has also been a friend and mentor of the greatest distinction for close to a decade. I hope that in some small way this serves as recompense for the hours, days, months, and years he spent toiling over my work. Perhaps that effort has not been entirely in vain.

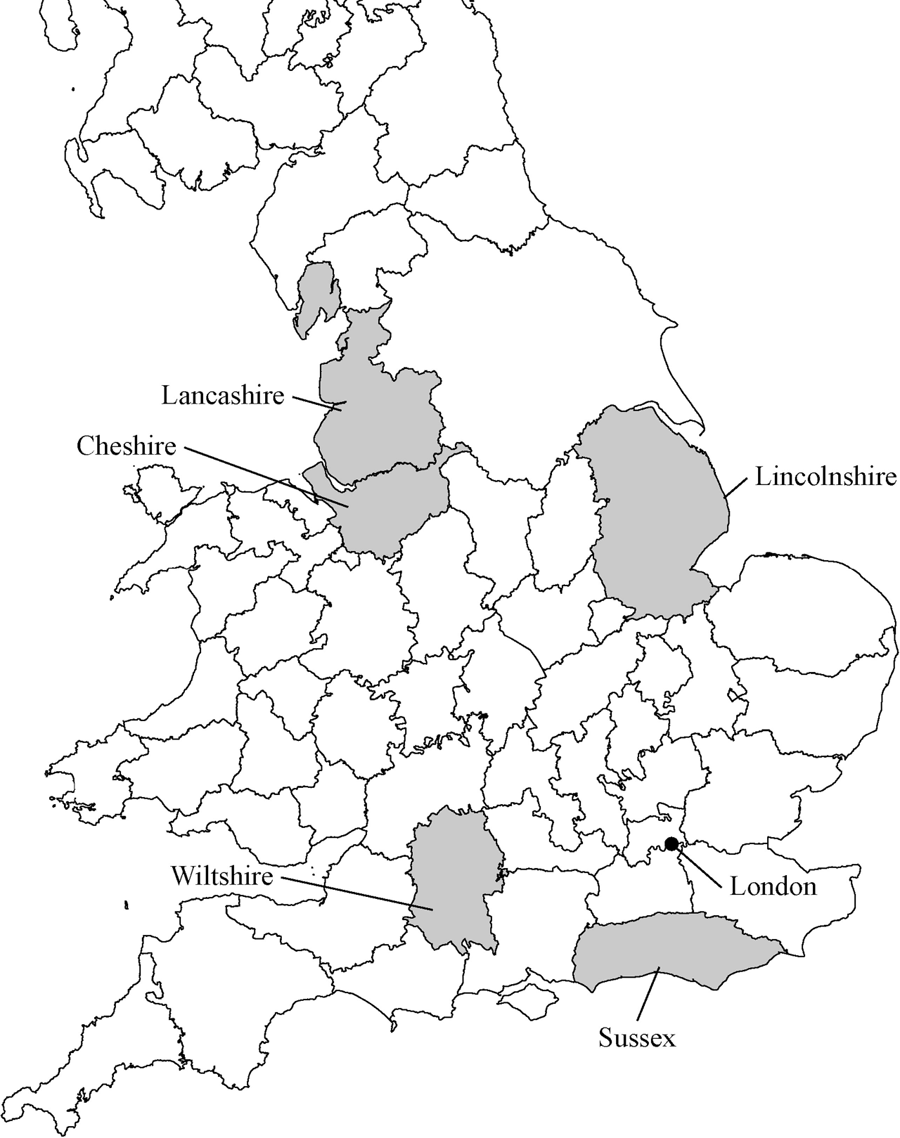

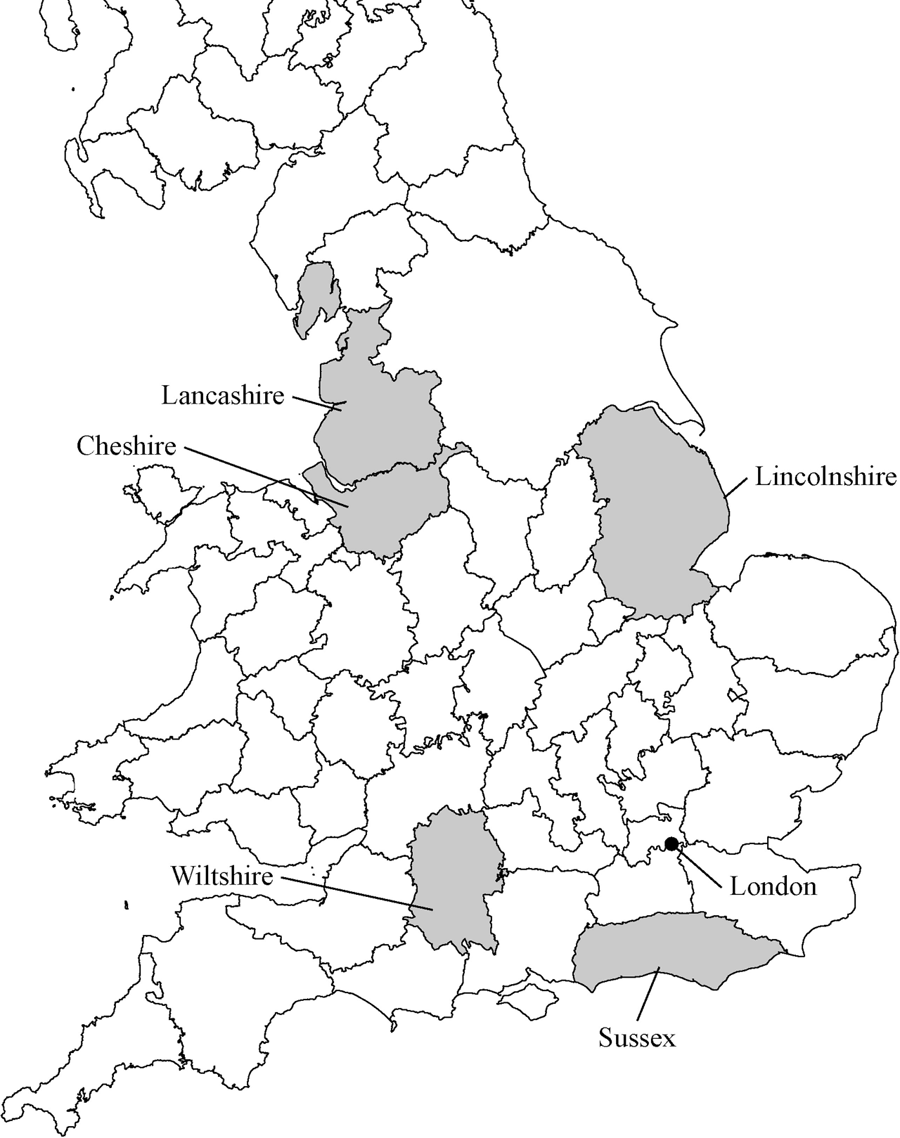

Supportive institutions and funding bodies are the life-blood of academic research. As such, gratitude is due to the Yale Center for the Study of Representative Institutions, the Jack Miller Center, the Whitney and Betty Macmillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale, and the Yale Boswell Editions for providing the funding necessary to complete this project. The Historic County Borders Project provided the open source data on early modern borders necessary for my creation of the maps featured in this book.

Yale University Press has proved to be a wonderful publisher. My editors, Jaya Chatterjee and Laura Davulis, deserve special praise for their championing of this book and their guidance throughout the publication process. Harry Haskell has been a sensitive and incisive copyeditor. Thanks are also due to the anonymous reviewers for their perceptive and constructive critiques.

My family has lived with this book for as long as I have been writing it. My parents, Jack and Nancy; my brothers Jack, Kaleb, John, Joey, and Josh; my sister Caitlin; and the extended Lockwood and Heid families have always supported my endeavors in whatever ways they could. I greatly appreciate their unflagging generosity and their forbearance of my ranting and rambling. My in-laws, Wendy, Donald, Emma, Eric, Barbara, and Tracy, have likewise shared the research and writing process in all its ups and downs, emotionally and intellectually.

Lucy Kaufman has been my intellectual sounding board, writing coach, and wellspring of support throughout this process and far beyond. Any thanks I give will never be sufficient recompense for her time, effort, and perseverance on my behalf. Quite simply, I would not be where I am today without her.

The Conquest of Death

Introduction

Revenge is a kind of wild justice; which the more mans nature runs to, the more ought the law to weed it out.

Francis Bacon, On Revenge (1625)

THE EYES OF THE STATE WERE everywhere in early modern England (

Figure 1. Map of the counties of early modern England

All of these parties had a financial stake in the outcome of the coroners inquest and the verdict it assigned. If the death was ruled to be a homicide, John Derrick would stand to receive a fee as coroner; a verdict of accident or suicide, however, would mean Derricks pains would go unrewarded. If the death was found to be an accident, Mr. Morgan could potentially lose the value of any piece of movable property that was deemed to have caused the accident. As the crown appointee who was granted the right to all forfeit goods, the almoner, whose agents were on the ground in Surrey, stood to gain Chennells goods and chattels if the verdict was suicide. Thomas Chennells widow, however, would lose all her inheritance if her husbands death was ruled to be suicide. Finally, one of Chennells

With so many competing interests it is no surprise that not every party present was fully satisfied with the process and outcome of the coroners inquest. As so often transpired in early modern England, dissatisfaction led inexorably to a lawsuit, and the dispute over Thomas Chennells death shifted venue to the Court of Star Chamber, where crown officials perused the records of coroner, almoner, witness, and heirs to determine the proper redistribution of the deceaseds property. The almoner brought suit against three members of the coroners jury, claiming that, in collusion with Chennells heirs, these men had bribed a local pauper to flee the county as if he were responsible for Chennells death, thus paving the way for a verdict of death by homicide. The men denied this charge, claiming that the almoner was pushing for a suicide verdict so as to gain the dead mans forfeit property. John Derrick, the coroner, was also sued for failing to return a verdict of any kind. Neighbors, witnesses, local agents of the almoner, and others were called to provide evidence, and the records produced by the coroner and his jury were examined, all to settle the matter of how a Surrey yeomans property was to be redistributed after his violent death.

While on the surface these events might seem mundane or routine, such litigation over the forfeit property of felons and the violently deceased performed an important function in early modern England. As the financial interests of heirs, creditors, coroners, and crown all rested on the outcome of the coroners inquest, few violent deaths went unnoticed, unexamined, or unexplained. Furthermore, these contestations over inquest verdicts created a new level of written documentation that allowed the representatives of the state new avenues and novel opportunities for the oversight of violent death in the early modern period. In turn, the advent of a new system of surveillance allowed the state to obtain a true monopoly of violence for the first time in English history. This is the story of how that monopoly came to exist and the judicial official whose primary purpose was its enforcement.

Next page