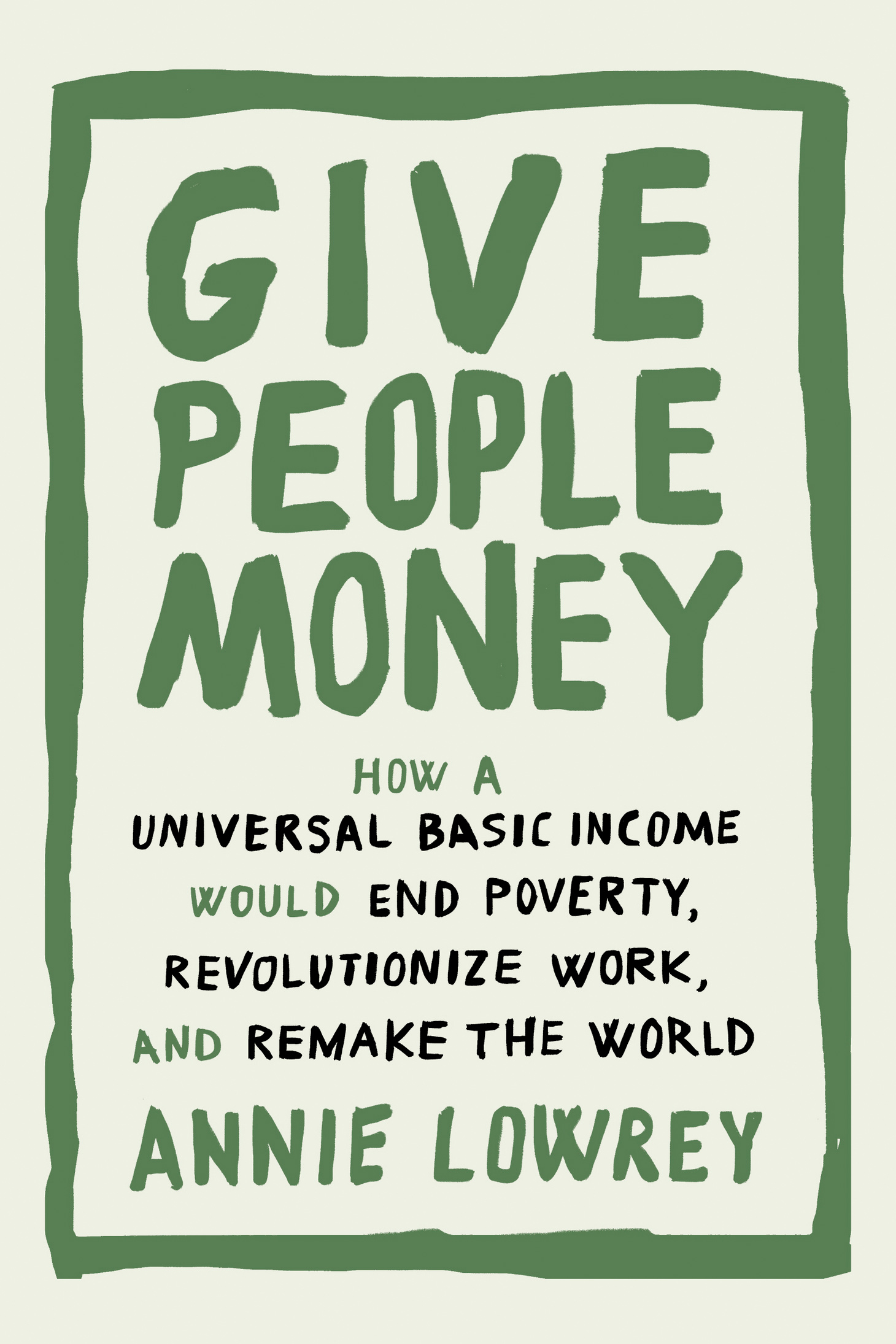

All rights reserved.

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Chapter Four is adapted from The Future of Not Working by Annie Lowrey, which appeared in The New York Times Magazine on February 23, 2017. Chapter Six is adapted from The People Left Behind When Only the Deserving Poor Get Help by Annie Lowrey, which originally appeared in The Atlantic on May 25, 2017.

Name: Lowrey, Annie, author.

Title: Give people money : how a universal basic income would end poverty, revolutionize work, and remake the world / Annie Lowrey.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017060432 | ISBN 9781524758769 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781524758776 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Guaranteed annual income. | PovertyGovernment policy.

INTRODUCTION

Wages for Breathing

One oppressively hot and muggy day in July, I stood at a military installation at the top of a mountain called Dorasan, overlooking the demilitarized zone between South Korea and North Korea. The central building was painted in camouflage and emblazoned with the hopeful phrase End of Separation, Beginning of Unification. On one side was a large, open observation deck with a number of telescopes aimed toward the Kaesong industrial area, a special pocket between the two countries where, up until recently, communist workers from the North would come and toil for capitalist companies from the South, earning $90 million in wages a year. A small gift shop sold soju liquor made by Northern workers and chocolate-covered soybeans grown in the demilitarized zone itself. (Dont like them? Mail them back for a refund, the package said.)

On the other side was a theater whose seats faced not a movie screen but windows looking out toward North Korea. In front, there was a labeled diorama. Here is a flag. Here is a factory. Here is a juche-inspiring statue of Kim Il Sung. See it there? Can you make out his face, his hands? Chinese tourists pointed between the diorama and the landscape, viewed through the summer haze.

Across the four-kilometer-wide demilitarized zone, the North Koreans were blasting propaganda music so loudly that I could hear not just the tunes but the words. I asked my tour guide, Soo-jin, what the song said. The usual, she responded. Stuff about how South Koreans are the tools of the Americans and the North Koreans will come to liberate us from our capitalist slavery. Looking at the denuded landscape before us, this bit of pomposity seemed impossibly sad, as did the incomplete tunnel from North to South scratched out beneath us, as did the little Potemkin village the North Koreans had set up in sight of the observation deck. It was supposedly home to two hundred families, who Pyongyang insisted were working a collective farm, using a child care center, schools, a hospital. Yet Seoul had determined that nobody had ever lived there, and the buildings were empty shells. Comrades would come turn the lights on and off to give the impression of activity. The North Koreans called it peace village; Soo-jin called it propaganda village.

A few members of the group I was traveling with, including myself, teared up at the stark difference between what was in front of us and what was behind. There is perhaps no place on earth that better represents the profound life-and-death power of our choices when it comes to government policy. Less than a lifetime ago, the two countries were one, their people a polity, their economies a single fabric. But the Cold Wars ideological and political rivalry between capitalism and communism had ripped them apart, dividing families and scarring both nations. Soo-jin talked openly about the separation of North Korea from the South as our national tragedy.

The Republic of Koreathe Southrocketed from third-world to first-world status, becoming one of only a handful of countries to do so in the postwar era. In 1960, about fifteen years after the division of the peninsula, its people were about as wealthy as those in the Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone. In 2016, they were closer income-wise to those in Japan, its former colonial occupier, and a brutal one. Citigroup now expects South Korea to be among the most prosperous countries on earth by 2040, richer even than the United States by some measures.

Yet the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, the North, has faltered and failed, particularly since the 1990s. It is a famine-scarred pariah state dominated by governmental graft and military buildup. Rare is it for a country to suffer such a miserable growth pattern without also suffering from the curse of natural disasters or the horrors of war. As of a few years ago, an estimated 40 percent of the population was living in extreme poverty, more than double the share of people in Sudan. Were war to befall the country, that proportion would inevitably rise.

Even from the remove of the observation deckenveloped in steam, hemmed in by barbed wire, patrolled by passive young men with assault riflesthe difference was obvious. You could see it. I could see it. The South Korean side of the border was lush with forest and riven with well-built highways. Everywhere, there were power lines, trains, docks, high-rise buildings. An hour south sat Seoul, as cosmopolitan and culturally rich a city as Paris, with far better infrastructure than New York or Los Angeles. But the North Korean side of the border was stripped of trees. People had perhaps cut them down for firewood and basic building supplies, Soo-jin told me. The roads were empty and plain, the buildings low and small. So were the people: North Koreans are now measurably shorter than their South Korean relatives, in part due to the stunting effects of malnutrition.

South Korea and North Korea demonstrated, so powerfully demonstrated, that what we often think of as economic circumstance is largely a product of policy. The way things are is really the way we choose for them to be. There is always a counterfactual. Perhaps that counterfactual is not as stark as it is at the demilitarized zone. But it is always there.

Imagine that a check showed up in your mailbox or your bank account every month.

The money would be enough to live on, but just barely. It might cover a room in a shared apartment, food, and bus fare. It would save you from destitution if you had just gotten out of prison, needed to leave an abusive partner, or could not find work. But it would not be enough to live particularly well on. Lets say that you could do anything you wanted with the money. It would come with no strings attached. You could use it to pay your bills. You could use it to go to college, or save it up for a down payment on a house. You could spend it on cigarettes and booze, or finance a life spent playing Candy Crush in your moms basement and noodling around on the Internet. Or you could use it to quit your job and make art, devote yourself to charitable works, or care for a sick child. Lets also say that you did not have to do anything to get the money. It would just show up every month, month after month, for as long as you lived. You would not have to be a specific age, have a child, own a home, or maintain a clean criminal record to get it. You just