MORNING STAR

THE SURREALIST REVOLUTION SERIES

Franklin Rosemont, Editor

A renowned current in poetry and the arts, Surrealism has also influenced psychoanalysis, anthropology, critical theory, politics, humor, popular culture, and everyday life. Illuminating its diversity and actuality, the Surrealist Revolution Series focuses on translations of original writings by participants in the international Surrealist movement and on critical studies of unexamined aspects of its development.

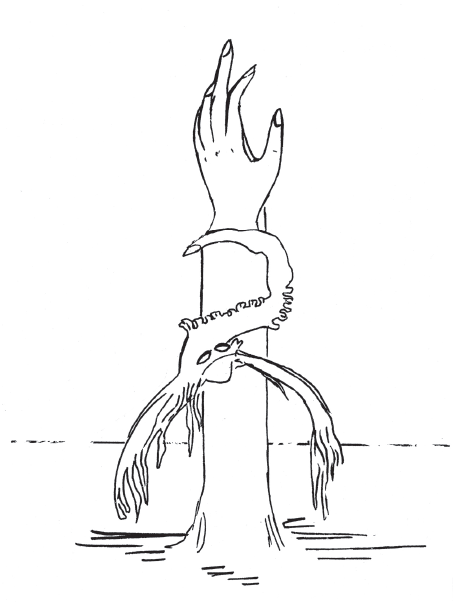

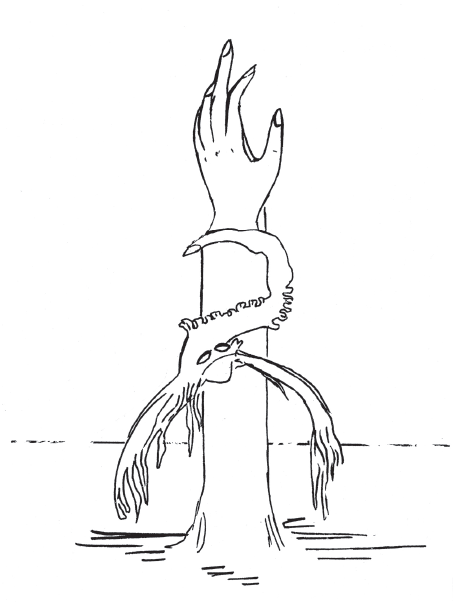

Nancy Joyce Peters, Drawing, 1976.

MORNING STAR

surrealism, marxism, anarchism, situationism, utopia

Michael Lwy

INTRODUCTION BY

Donald LaCoss

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS  AUSTIN

AUSTIN

Copyright 2009 by Michael Lwy

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2009

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 787137819

www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Lwy, Michael, 1938

[toile du matin. English]

Morning star : surrealism, marxism, anarchism, situationism, utopia / Michael Lwy ; introduction by Donald LaCoss. 1st ed.

p. cm. (The surrealist revolution series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-71894-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-292-79363-7 (e-book) ISBN 978-0-292-71894-4 (individual e-book)

1. French literature20th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. Surrealism (Literature)FranceHistory. 3. Surrealism France. I. Title.

PQ307.S95 L69413

840.9'1163dc22

2008033358

Previously published in part as Ltoile du matin: surralisme et marxisme, ditions Syllepse, 2000

The author wishes to acknowledge Myrna Bell Rochester, Penelope Rosemont, and Victoria Davis.

CONTENTS

Donald LaCoss

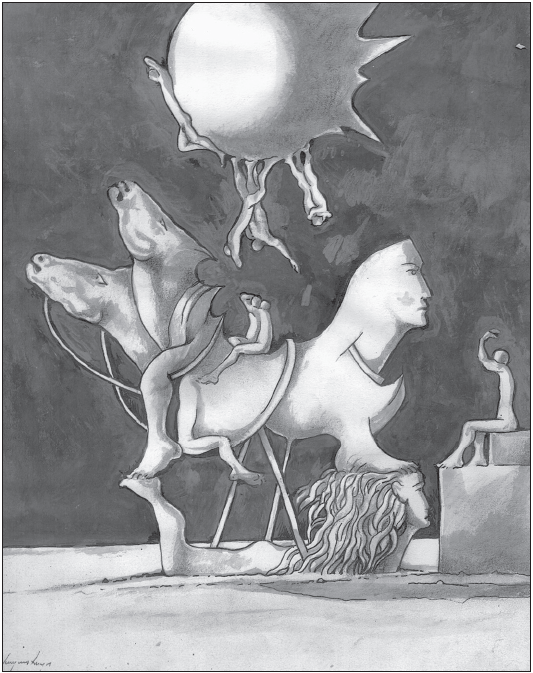

Artur do Cruzeiro Seixas, Beyond Words, 2007.

INTRODUCTION

Surrealism and Romantic Anticapitalism

Donald LaCoss

The world has long been dreaming of something that it could actualize if only it becomes conscious of it.

Karl Marx, in a letter to Arnold Ruge, September 1843

Despite their stubborn and often impossible fight against unfreedom in all its forms, the Surrealists have long been ignored in most discussions of social change movements. Hopefully, some headway can be made against these exclusions with more English-language translations of important studies of the intersections between Surrealism, culture, and politics, such as Michael Lwys collection from 2001, Ltoile du matin: surralisme et marxisme. From its first paragraph, Lwy lays out a stirring and highly suggestive portrayal of Surrealism as a movement of psychical revolt and the subversive reenchantment of the world, and he maintains this inspiring perspective throughout.

Surrealism is not, has never been, and will never be a school of literary modernism or a group of artists with a shared outlook, Lwy persuasively argues. Rather, it is better understood as an anthropological study of liberty read through an optic of independent, revolutionary Hegelo-Marxist dialectics barbed with strikingly original libertarian impulses. Lwys approach underscores the integral necessity of binding internal revolts of consciousness to outbursts of insurgent collective action, a main thrust of Surrealist activity since at least the mid-1930s (one need only read Andr Bretons deliriously Hegelian Communicating Vessels (1931) and The Political Position of Surrealism (1935) in order to excavate the theoretical frame). In short, the images, objects, and texts associated with Surrealismlets say Meret Oppenheims famous fur-lined teacup or Bretons antinovel Nadjaare merely leftovers of a much more complicated process, the empty wine bottle on the table the morning after a satisfying evening of intense conversation or the footprints left behind in the snow after a passionate midnight dance under a dark sky.

Lwys inquiries begin with a look at the edgy persistence of Romanticism within the movement. In fact, the morning star of this collections title is a Romantic motif that refers to Victor Hugos unfinished epic poem of 1886 about the fall of Satan, a poem upon which Breton meditated in his essay on collective myth and liberty, Arcanum 17 (1944). Lwy, who has called the conclusion of Arcanum 17 one of the most luminous books of Surrealism, regards the morning starthe planet Venus when it appeared in the eastern sky near dawn, also known as Lucifer (light-bearer) by ancient Roman stargazersas an allegory for Surrealisms drive to radically embody Romanticisms revolutionary dimensions.

Without doubt, Surrealists have drunk deeply from the underground springs of Romanticism. Breton was most explicit about this when he pointed out that, although historically it appeared at the tail end of Romanticism, Surrealism was an excessively prehensile tail. Since the movements inception in 1919 and continuing to the present day, Surrealism has refused the more dehumanizing legacies of the Enlightenment that were championed by the bourgeois and their supporters, much in the same way that so many German Romantics had objected to similar proposals advocated by enthusiasts of the Aufklrung (Enlightenment) thinkers.

Romanticism is a roiling buildup of social, political, and cultural forces that, like lightning in a fast-moving thunderstorm, forks and branches off in a greatly diverse number of directions. Whereas a number of German Romantics resisted the Enlightenment from a variety of perspectives across the modern political spectrum, Lwy has long argued for a hidden history to Romanticism that chronicles a specifically radical pursuit of a decentralized, directly democratic civil society committed to human creativity, artistic autonomy, and open expression. Generally speaking, the political and cultural pattern of this revolutionary form of Romanticism refuses both the illusion of returning to the communities of the past and the reconciliation with the capitalist present, seeking a solution in the future. In this school... nostalgia for the past does not disappear but is projected toward a postcapitalist future.

At times, these Romantics both opposed the Enlightenment and supported itin the latter cases, the Romantics called for extending ruthless Enlightenment critique even further and deeper demolishing those very interests that the Enlightenment had helped to create in the first place, namely, the bourgeois-liberal mentalitys context within capitalist social relations. More generally, though, the revolutionary Romantics decried the ugly, disinterested rationality of the Enlightenment that garbled ideas of freedom and community into the modern States administrative systems of social control and progress. Similarly, they objected to the political economy of Enlightened liberalism that had transformed mercantilism into capitalism by furthering the unregulated circulation of capital, goods, and labor while simultaneously encouraging accumulation, enshrining private property, enforcing a class system in which alienated labor was the only thing of value for workers, and estranging the natural world from civilization in order to establish a stockpile of resources ripe for capitalist abuse. Revolutionary Romantic resistance to Enlightenment theory and practice was organized within the innumerable spaces of irreconcilable contradictions that riddled liberal-bourgeois industrial civilization in the nineteenth century; the resistance opposed the intensifying trends of colonial exploitation, bureaucratic power, and State violence that were (and remain) so central to everyday life in a Western civilization.

Next page

AUSTIN

AUSTIN The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).