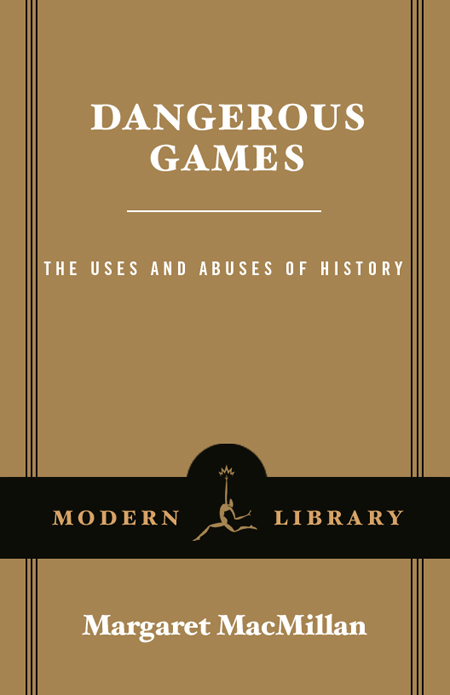

M ODERN L IBRARY C HRONICLES

Currently Available

K AREN A RMSTRONG on Islam

D AVID B ERLINSKI on mathematics

R ICHARD B ESSEL on Nazi Germany

I AN B URUMA on modern Japan

P ATRICK C OLLINSON on the Reformation

F ELIPE F ERNNDEZ -A RMESTO on the Americas

L AWRENCE M. F RIEDMAN on law in America

P AUL F USSELL on World War II in Europe

F. G ONZLEZ -C RUSSI on the history of medicine

P ETER G REEN on the Hellenistic Age

A LISTAIR H ORNE on the age of Napoleon

P AUL J OHNSON on the Renaissance

F RANK K ERMODE on the age of Shakespeare

J OEL K OTKIN on the city

H ANS K NG on the Catholic Church

M ARK K URLANSKY on nonviolence

E DWARD J. LARSON on the theory of evolution

M ARTIN M ARTY on the history of Christianity

M ARK M AZOWER on the Balkans

J OHN M ICKLETHWAIT and A DRIAN W OOLDRIDGE on the company

A NTHONY P AGDEN on peoples and empires

R ICHARD P IPES on Communism

C OLIN R ENFREW on prehistory

K EVIN S TARR on California

M ICHAEL S TRMER on the German Empire

G EORGE V ECSEY on baseball

M ILTON V IORST on the Middle East

A. N. W ILSON on London

R OBERT S. W ISTRICH on the Holocaust

G ORDON S. W OOD on the American Revolution

Forthcoming

T IM B LANNING on romanticism

A LAN B RINKLEY on the Great Depression

B RUCE C UMINGS on the Korean War

J AMES D AVIDSON on the Golden Age of Athens

S EAMUS D EANE on the Irish

J EFFREY E. G ARTEN on globalization

J ASON G OODWIN on the Ottoman Empire

R IK K IRKLAND on capitalism

S TEPHEN K OTKIN on the fall of Communism

B ERNARD L EWIS on the Holy Land

F REDRIK L OGEVALL on the Vietnam War

P ANKAJ M ISHRA on the rise of modern India

O RVILLE S CHELL on modern China

C HRISTINE S TANSELL on feminism

A LEXANDER S TILLE on fascist Italy

C ATHARINE R. S TIMPSON on the university

A LSO BY M ARGARET M AC M ILLAN

Women of the Raj:

The Mothers, Wives, and Daughters of the British Empire in India

Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World

Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World

C ONTENTS

8.

I NTRODUCTION

History is something we all do, even if, like the man who discovered he was writing prose, we do not always realize it. We want to make sense of our own lives, and often we wonder about our place in our own societies and how we got to be here. So we tell ourselves stories, not always true ones, and we ask questions about ourselves. Such stories and questions inevitably lead us to the past. How did I grow up to be the person I am? Who were my parents? My grandparents? As individuals, we are all, at least in part, products of our own histories, which include our geographical place, our times, our social classes, and our family backgrounds. I am a Canadian who has grown up in Canada, and so I have enjoyed an extraordinary period, unusual in much of the worlds history, of peace, stability, and prosperity. That has surely shaped the ways in which I look at the world, perhaps with more optimism about things getting better than I might have if I had grown up in Afghanistan or Somalia. And I am also a product of my parents and grandparents history. I grew up with some knowledge, incomplete and fragmentary, to be sure, of World War II, which my father fought in, and of World War I, which drew in both my grandfathers.

We use history to understand ourselves, and we ought to use it to understand others. If we find out that an acquaintance has suffered a catastrophe, that knowledge helps us to avoid causing him pain. (If we find that he has enjoyed great good luck, that may affect how we treat him in another way!) We can never assume that we are all the same, and that is as true in business and politics as it is in personal relations. How can we Canadians understand the often passionate feelings of French nationalists in Quebec if we do not know something about the past that has shaped and continues to shape them, the memories of the conquest by the British in 1759 and the sense that French speakers had become second-class citizens? Or the mixture of resentment and pride that so many Scots feel toward England now that Scotland has struck oil? If we know nothing of what the loss of the Civil War and Reconstruction meant to Southern whites, how can we understand their resentment toward Yankees that has lingered into the present day? Without knowing the history of slavery and the discrimination and frequent violence that blacks suffered even after emancipation, we cannot begin to grasp the complexities of the relationship between the races in the United States. In international affairs, how can we understand the deep hostility between Palestinians and Israelis without knowing something of their tragic conflicts?

History is bunk, Henry Ford famously said, and it is sometimes hard for us, perhaps especially in North America, to recognize that history is not a dead subject. It does not lie there safely in the past for us to look at when the mood takes us. History can be helpful; it can also be very dangerous. It is wiser to think of history not as a pile of dead leaves or a collection of dusty artifacts but as a pool, sometimes benign, often sulfurous, that lies under the present, silently shaping our institutions, our ways of thought, our likes and dislikes. We call on it, even in North America, for validation and for lessons and advice. Validation, whether of group identities, for demands, or for justification, almost always comes from using the past. You feel your life has a meaning if you are part of a much larger group, which predated your existence and which will survive you (carrying, however, some of your essence into the future). Sometimes we abuse history, creating one-sided or false histories to justify treating others badly, seizing their land, for example, or killing them. There are also many lessons and much advice offered by history, and it is easy to pick and choose what you want. The past can be used for almost anything you want to do in the present. We abuse it when we create lies about the past or write histories that show only one perspective. We can draw our lessons carefully or badly. That does not mean we should not look to history for understanding, support, and help; it does mean that we should do so with care.