To my parents, who taught me to live by the words of the Bard of the Brahmaputra:

Bhabibo kunenu kuwa?...

Foreword

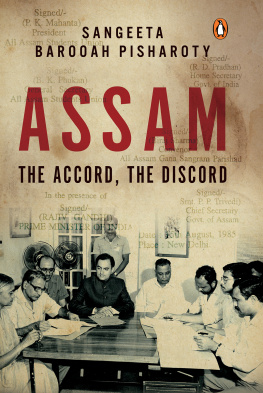

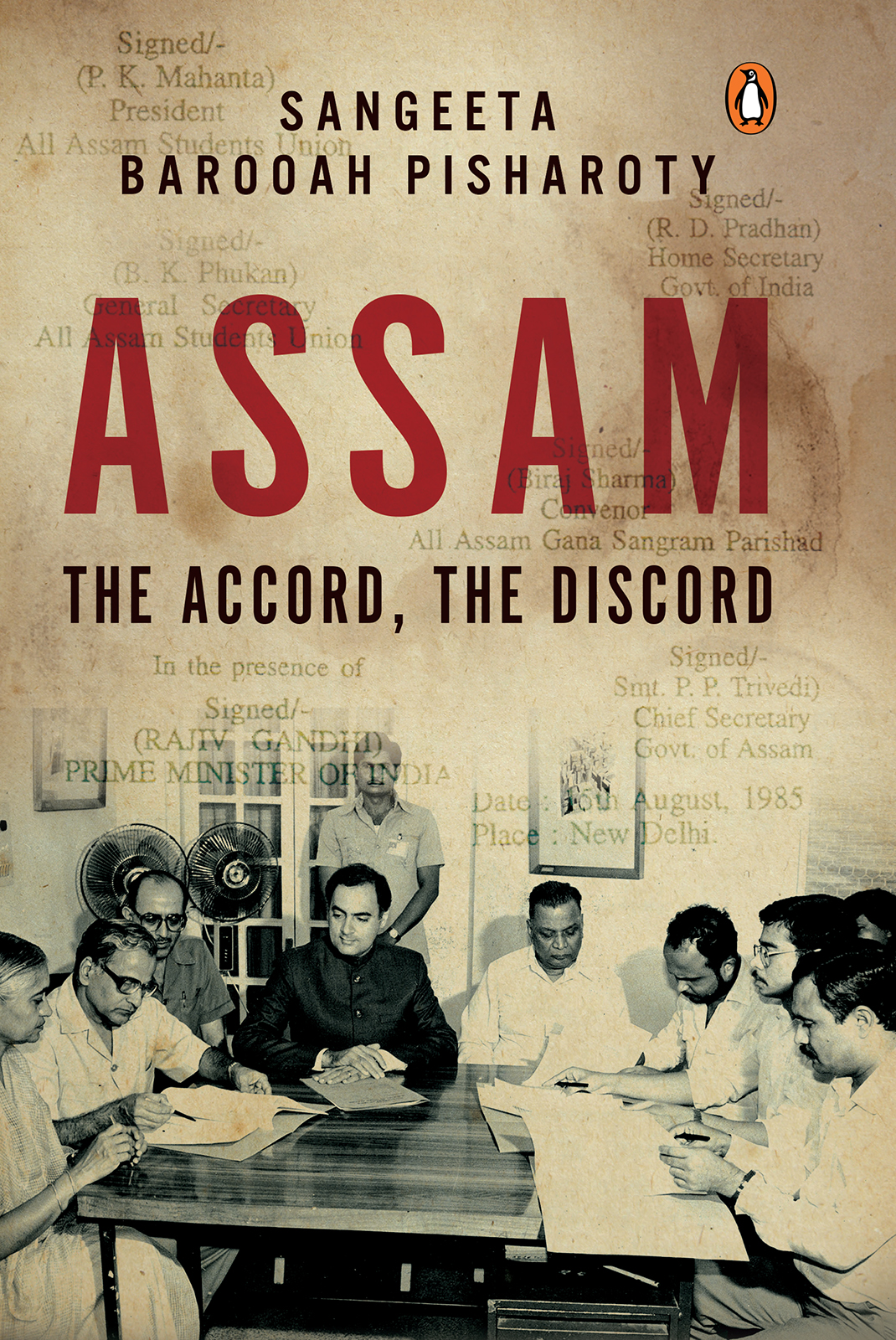

With attention to detail and dogged determination to get at the facts and to the heart of issues that have long troubled Assam (and India), Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty has provided us with a book that challenges assumptions and lays out the realities. Her work in Assam: The Accord, the Discord reflects conditions not just at Ground Zero but also brings to the fore the machinations of power-broking, decision-making and unmasks the protagonists who have long dominated the headlines and the political stage of the state. The way these conditions have meshed and conflicted, grows in nuance and bluntness, page after page, layer by layer, person by person, party by party, community by community.

There are detailed chapters going over the issue of the Assam insurgency, ethnic risings and the growth of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) across the Brahmaputra Valley, as well as the internal schisms within the powerful student organization All Assam Students Union (AASU). The way the Assamese Muslim leaders of AASU parted ways with the traditional leadership is also known but she has extracted telling details. These are stories told with compelling force.

To her credit, Sangeeta covers this tricky terrain with the ease of a veteran reporter, honed by extensive travel and interviews with many. I am glad she has used and given credit to my uncle, the historian, Nirode Barooah, whose pioneering work on Gopinath Bardoloi and the latters battle for Assams soul has not been given its rightful pride of place.

It is not the place of a foreword to dwell on detail about the book that is being discussed. But there are startling revelations and confirmations about involvement of members of AASU in filing random complaints against alleged foreigners in the Mangaldoi constituency in 1978 with help from police officials. This followed the revision of polls after the death of a member of Parliament; the revision turned up 47,000 or so foreigners and triggered the anti-immigrant movement in Assam that transformed the political landscape of the entire North-east and other parts of India.

The word Bangladeshi has become a pejorative but is used extensively in a charged political atmosphere. Words such as ghuspetia (infiltrators), videshi (foreigner), etc. are tossed about with abandon. The pattern of random complaints and harassment is also seen in the way unidentified persons have filed such complaints against over 2,00,000 persons in the ongoing, controversial National Register of Citizens (NRC). This is unconstitutional and yet is protected by a ruling of the Supreme Court.

One person I know said his family members had received five complaints in this scattershot campaign of complaints. They had all lived in Assam for over seventy years and had to rush around to reprove their identity. Their only marker was that they were Muslims of Bengali origin but now can speak Assamese as fluently as any one. It raises a fundamental issuehow many markers of our Indianness and citizenry do we need beyond passports, ration cards, voter IDs and PAN cards. Time and again, we have seen that the NRC process is wrapped in arbitrariness with case after case of Indians being targeted just because they have a different religion. Sangeeta has done well in a detailed study of the process to point out its shortcomings and pitfalls, but also the opportunities for change.

As the NRC rolls on relentlessly, despite the outcry that is being generated, we note that judges are being created out of lawyers yet again by further lowering the years of legal experience to become members of tribunals adjucating on the cases of those accused of being foreigners.

We are increasingly seen to be at odds with the fundamentals of our Constitution and the canons of international law as well as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which protect and provide for the most vulnerable and weak.

I am reminded here of Article 21 of the Constitution which proclaims that no one (not just a citizen but no one) can be deprived of his/her life or liberty in the territory of India without due process. That is the duty enjoined on everyone who lives in Indiathat no one be harmed without the process of law.

That is why this book is so important. It reminds us of what we are each called to do, without fear or favour: our constitutional duty.

Sangeetas work, reflected in her consistent writing over years in different media, represents both a benchmark and a wake-up call to deal with issues of misgovernance, alienation, arbitrariness and prejudice. It is also a reflection of her own deep concerns, mirrored in the personal anecdotes which she slips into the narrative, seamlessly and poignantly, which enrich the telling of a larger, deeply compelling and disturbing story of a people divided, seemingly helpless as a toxic mix of hate, suspicion and harm threatens to overwhelm them.

New Delhi

July 2019

Sanjoy Hazarika

Introduction

The kernel of this book lies in an urge to step back in time, locate some of my childhood memories of Assam and contextualize them to events of history.

The blood that spilled on the streets during the six-year-long, anti-foreigner agitation, or Assam Movement of 19791985, had not quite dried up when army boots arrived at our doors in the early 1990s. Even then, justice eluded the dead. The Assam Accord signed between the Government of India and the leaders of the Assam Movement in 1985 didnt bring permanent peace to the state and seemed to have delivered only discord and divisions. It polluted the politics of the state. It spawned insurgency. The common people were caught in a bind; they didnt know who was the enemy, who a friendthe state or non-state actors?

Amidst such hostilities, several from my generation, including me, left Assam for Delhi in the early 1990s, forced to choose between home and a future that the state could not promise us at that time. I have had this urge for a while to go back in time and try and pick up the pieces from three decades ago, hold them up to see what was lost, what was gained, if anything, and what of it was mine.

However, it turned out that my personal nostalgia had to give way to a more pressing national need. My journalistic work in Assam led me to realize that it was pertinent to set the Assam Movement against the conundrum that the north-eastern state finds itself in presentlythe controversial updating exercise of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), 1951, and the vehement public opposition to insert an amendment to the Citizenship Act, 1955, by the Narendra Modiled National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government.