Series page

History of Computing

William Aspray and Thomas J. Misa, editors

Janet Abbate, Recoding Gender: Womens Changing Participation in Computing

John Agar, The Government Machine: A Revolutionary History of the Computer

William Aspray and Paul E. Ceruzzi, The Internet and American Business

William Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing

Charles J. Bashe, Lyle R. Johnson, John H. Palmer, and Emerson W. Pugh, IBMs Early Computers: A Technical History

Martin Campbell-Kelly, From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry

Paul E. Ceruzzi, A History of Modern Computing, 2nd ed.

I. Bernard Cohen, Howard Aiken: Portrait of a Computer Pioneer

I. Bernard Cohen and Gregory W. Welch, editors, Makin Numbers: Howard Aiken and the Computer

Nathan L. Ensmenger, The Computer Boys Take Over: Computers, Programmers, and the Politics of Technical Expertise

Thomas Haigh, Mark Priestley, and Crispin Rope, ENIAC in Action: Making and Remaking the Modern Computer

John Hendry, Innovating for Failure: Government Policy and the Early British Computer Industry

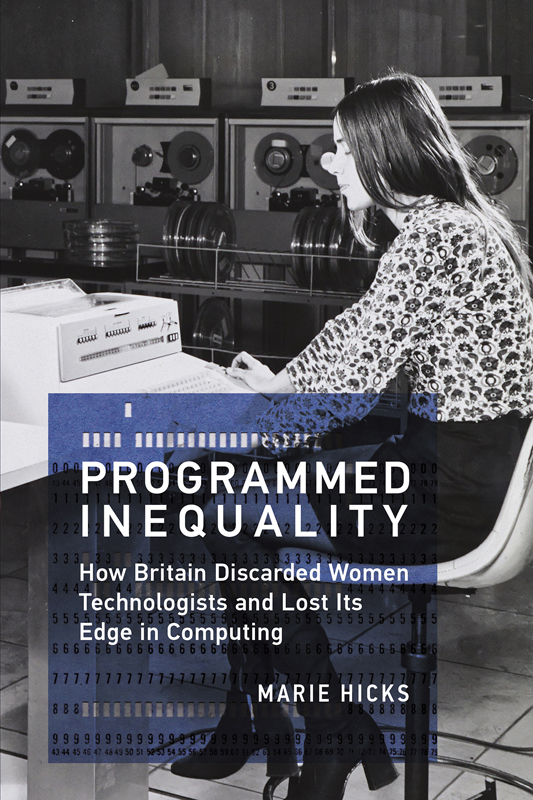

Marie Hicks, Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing

Michael Lindgren, Glory and Failure: The Difference Engines of Johann Mller, Charles Babbage, and Georg and Edvard Scheutz

David E. Lundstrom, A Few Good Men from Univac

Ren Moreau, The Computer Comes of Age: The People, the Hardware, and the Software

Arthur L. Norberg, Computers and Commerce: A Study of Technology and Management at Eckert-Mauchly Computer Company, Engineering Research Associates, and Remington Rand, 19461957

Emerson W. Pugh, Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology

Emerson W. Pugh, Memories that Shaped an Industry

Emerson W. Pugh, Lyle R. Johnson, and John H. Palmer, IBMs 360 and Early 370 Systems

Kent C. Redmond and Thomas M. Smith, From Whirlwind to MITRE: The R&D Story of the SAGE Air Defense Computer

Alex Roland with Philip Shiman, Strategic Computing: DARPA and the Quest for Machine Intelligence, 19831993

Ral Rojas and Ulf Hashagen, editors, The First Computers: History and Architectures

Dinesh C. Sharma, The Outsourcer: The Story of Indias IT Revolution

Dorothy Stein, Ada: A Life and a Legacy

John N. Vardalas, The Computer Revolution in Canada: Building National Technological Competence

Maurice V. Wilkes, Memoirs of a Computer Pioneer

Programmed Inequality

How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing

Marie Hicks

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hicks, Marie, author.

Title: Programmed inequality : how Britain discarded women technologists and lost its edge in computing / Marie Hicks.

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, 2017. | Series: History of computing | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016021258 | ISBN 9780262035545 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262342926

Subjects: LCSH: Women--Employment--Great Britain--History--20th century. | Sex discrimination in employment--Great Britain--History--20th century. | Electronic data processing--Great Britain--History. | Technocracy. | MESH: Computers.

Classification: LCC HD6135 .H53 2017 | DDC 331.40941/09045--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016021258

ePub Version 1.0

Dedication

For Britt

Epigraph

However revolutionary the technology, account must always be taken of constraints upon its speed of adoption and diffusion and hence, derived manpower demand. Technological innovation does not exist in a vacuum; it forms but one element of a complex social system.

UK Computer Sector Working Party, Manpower Subcommittee, 1979

Note

For more information, see Economic Development Committee for the Electronics Industry, Computer Sector Working Party, Manpower Sub-Committee, Discussion Papers on Education and Training; Final Report and Government Response, 19791980, ED 212/216, the National Archives of the United Kingdom (TNA).

Acknowledgments

The idea for this book began to take shape when I was working as a UNIX systems administrator in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Division at Harvard University. I had graduated from Harvard with a degree in history, but no computer science courses. My boss, Peg Schafer, hired me and many other people without formal computer science training because she felt that a good systems administrator could be made from any reasonably intelligent person. Peg believed that the most important things sysadmins needed to knowlike how to handle people coextensively with technical problemswere learned on the job. The odd gender split in that workplace, with my older supervisors being mostly women and my younger peers being mostly men, and the conversations we all had about this, led me to wonder about gendered labor change in computings past. It eventually resulted in my graduate research and this book.

When I entered the field over a decade ago, the topic of gender in computer history had nowhere near the cultural resonance or acceptance that it has today. When I told people about my project, I often was met with blank stares or occasionally even open hostility. But I never had this problem within the Society for the History of Technology and its Special Interest Group on Computers and Information in Society, whose members were always incredibly kind and welcoming. That these groups made me feel as though I were working on an important topic made a world of difference to my ability to complete this project. In addition, both the National Science Foundation and the Charles Babbage Institute for the History of Computing (particularly the fellowship endowed by the Tomash family) provided support that allowed me to do much of the research for the dissertation upon which this book is based.

I especially would like to convey my gratitude to Cathy Gillespie, Ann Sayce, and Colin Hobsonformer computer workers who spoke to me about their time in British computing in the 1960s and beyond and who were extremely generous with their time and stories. In addition to the useful tacit knowledge and background information they shared, their perspectives lent an immediacy and warmth to this history that archives alone could not. My thanks also go to the many dedicated archivists and librarians who guided my inquiries at the UK National Archives, the British Library, the UK National Archive for the History of Computing at the University of Manchester, the Modern Records Center at the University of Warwick, the Womens Library in London, and the Vickers Archive at Cambridge University.

The comments of anonymous reviewers of the manuscript and the many people who read versions of drafts that became the chapters in this book provided invaluable insights. Although space and the vicissitudes of memory limit my ability to thank everyone who made an important contribution to this project, I would like to note the major contributions of my advisor and my dissertation committee membersAlex Roland, Susan Thorne, Ross Bassett, and Robyn Wiegman. Many of my fellow grad students at Duke University supported and encouraged me during our years together in the program and afterwardin particular, Anne-Marie Angelo, Eric Brandom, Andrew Byers, Mitch Fraas, and Jacob Remes. I would also like to thank Katie Helke, Justin Kehoe, and the rest of the editorial team at the MIT Press.

Next page