THIS BOOK BEGAN while I taught in the Rhetoric Department at the University of California, Berkeley. I am particularly indebted to Karen Feldman, who helped make the joys of rhetorical analysis more clear to me, and to Judith Butler, who, besides being an inspiration through her writing, was the chair of rhetoric at that time and instrumental in my coming to Berkeley. Karen has been one of my most faithful readers, and her precise, careful way of thinking and writing remains an admirable example. Victoria Kahn, who had left the Rhetoric Department by the time I arrived, was extremely gracious and helpful, both as a superb writer in her own right and as a source of encouragement, advice, and support. I also learned a great deal from Felipe Guterriez, Michael Mascuch, Nancy Weston, Pheng Cheah, Caroline Humfress, Ramona Naddaff, Fred Dolan, and David Bates.

At San Francisco State University, I have been privileged to know Gerard Heather and Matthew Stolz (now deceased), both political theorists who took me under their wings when I got there and who have been steadfast friends ever since. Sandra Luft familiarized me with the work of Aryeh Botwinick and has been a great colleague. I also appreciate the support and friendship of Anatole Anton and Roberto Rivera, as well as my dean and fellow political theorist, Joel Kassiola. Above all, I am grateful to Deb Cohler, Amy Sueyoshi, and Angelika von Wahl. All three worked in a reading group with me. Their support and encouragement helped bring the book along and untangled some of the denser sections. Deb has been my main reader from beginning to end and her guidance and friendship were indispensable. Angelika has been a wonderful office mate and friend as well as insightful reader. Thanks to Tiffany Willoughby-Herard, an exciting new colleague and friend. The presidential leave award I received for the fall of 2006 was very helpful in allowing me to finish this book.

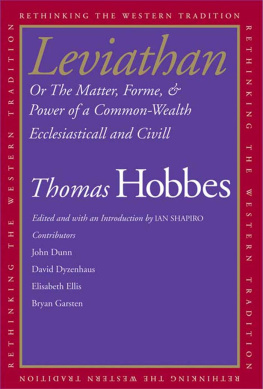

I also want to thank my students at both Berkeley and SFSU, particularly those in my recent graduate seminar on Walter Benjamin. Teaching these works (including Leviathan many, many times) and trying out ideas by discussing them with students has been a vital part of how I have studied and read these texts. Among students who stand out in this regard are Dieyana Ruzgani, Matt Freeman, Colin Dingler, Rebecca Goldman, Anatoli Ignatov, J. P. Cauvin, John Wesley Vavricka, Adam White, Noa Bar, Randall Cohn, and Rebecca Stillman.

Other friends and colleagues whose help has been essential include above all my dear friend Nasser Hussain, just for being who he is and for helping me think beyond the narrowest confines of political theory. Mark Andrejevic has inspired me with his insights and approach to philosophy. Tom Dumm and Austin Sarat have both been unfailingly encouraging, tracking the progress of this book from conference to conference. Jodi Dean and Paul Passavant actually helped me enjoy going to American Political Science Association meetings. Wendy Brown remains one of my greatest influences, a model for how to write and think and also how to support ones students and their work. Peter Fitzpatrick and I have from an early stage shared our mutual interest in Hobbes, and he has helped me to think to a greater and deeper extent about Leviathan. Peter Goodrich has likewise challenged me to think more deeply about texts and interpretation in general. Samantha Frost has written a great (forthcoming) book on Hobbes and I enjoyed following its development. I also want to thank many teachers and colleagues, beginning with the tragically departed Michael Rogin, whom I was lucky to have as dissertation chair and mentor. I also want to thank Hanna Pitkin, Shannon Stimson, Bev Crawford, Bill Chaloupka, Thomas Laqueur, Norman Jacobson, Jane Bennett, Bonnie Honig, Jackie Stevens, Samera Esmeir, Aaron Belkin, Thomas Burke, Javier Corrales, Pavel Machala, Nicole Watts, Francis Neely, and many others. Although I dont know him personally, I also feel very inspired by Richard Flathman; a great deal of this book is an engagement with his work.

Wendy Lochner at Columbia has been an ideal editor; she understood my project from the start and worked with me to bring it to fruition. Chris tine Mortlock and Susan Pensak have been very helpful, as has my copyeditor, Tom Pitoniak. I also wanted to acknowledge the help and encouragement of Carrie Mullen, Courtney Berger, Jason Frank, Colin Perrin, and Toby Wahl.

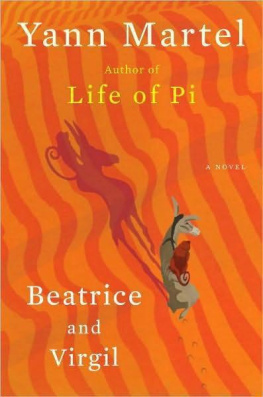

I have a large and wonderful family to thank: my parents, Huguette and Ralph Martel; my brother Django and sister-in-law Shalini Arora; my wonderful friends Lisa Guerin, Chris Clay, and Lisa Clampitt; and my nuclear familymy partner, Carlos; my children, Jacques and Rocio; and my coparents, Nina and Kathryn, and Elic and Mark. I feel lucky to have them all in my life.

Earlier versions of some of the arguments I make in this book appeared (or will appear) in the following journal articles: Earlier versions of parts of ) will appear in Amo: Volo ut sis: Love, Willing, and Arendts Reluctant Embrace of Sovereignty, Philosophy and Social Criticism (forthcoming).

Adler, Laure. Dans les pas de Hannah Arendt. Paris: Gallimard, 2005.

Adorno, Theodore W., and Walter Benjamin. The Complete Correspondence, 19281940. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Agamben, Giorgio. The Messiah and the Sovereign. In Daniel Heller-Roazen, ed., Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Andrejevic, Mark. Reality TV: The Work of Being Watched. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004.

Arendt, Hannah, The Concept of History, What Is Authority, and What Is Freedom? In Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought. New York: Penguin, 1954.

____. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958.

____. On Revolution. New York: Penguin, 1968.

____. Willing. In The Life of the Mind. New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

Ashcraft, Richard. Revolutionary Politics and Lockes Two Treatises of Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Aston, Margaret. Englands Iconoclasts. Vol 1. Laws Against Images. Oxford: Clarendon, 1988.

Austin, J. L. How to Do Things with Words. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965.

Barnouw, Jeffrey. Persuasion in Hobbess Leviathan. Hobbes Studies 1 (1988): 325.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

____. Central Park. Translated by Lloyd Spencer. New German Critique 34 (Winter 1985): 3258.

____. Critique of Violence. In Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. New York: Schocken, 1978.

____. Eduard Fuchs, Collector and Historian. In Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, eds Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Vol. 3, 19351938. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap, 2002.

____. On Some Motifs in Baudelaire. In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. New York: Schocken, 1968.

____. The Origin of German Tragic Drama (Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels). London: NLB, 1977.

____. Theological-Political Fragment. In Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, eds., Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Vol. 3, 19351938. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap, 2002.

____. Theses on the Philosophy of History. In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. New York: Schocken, 1968.

____. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. New York: Schocken, 1968.

____. The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire