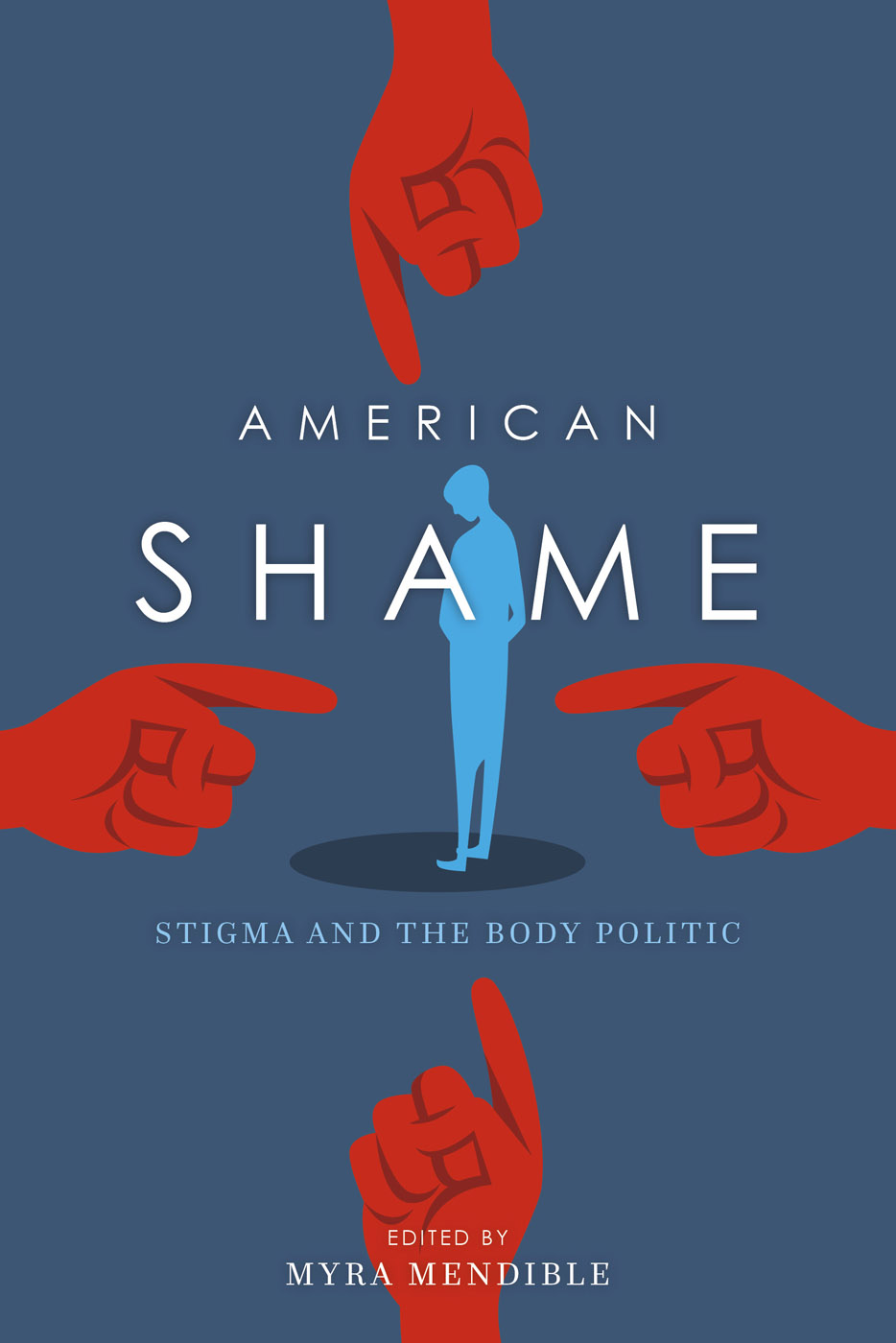

AMERICAN

SHAME

AMERICAN

SHAME

STIGMA AND THE BODY POLITIC

EDITED BY

MYRA MENDIBLE

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2016 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-01979-0 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-01982-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-01986-8 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 21 20 19 18 17 16

To Ernesto, for always believing in me.

And as long as you are in any way ashamed before yourself, you do not yet belong with us.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

CONTENTS

Myra Mendible

Karen Weingarten

Daniel McNeil

Leah Perry

Frances Negrn-Muntaner

Renee Lee Gardner

Meghan Griffin

Noel Glover

Madeline Walker

Michael Rancourt

Anthony Carlton Cooke

Megan Tagle Adams

Emily L. Newman

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe a debt of gratitude to Evelin Gerda Lindner for her tireless efforts on behalf of human dignity. A public intellectual, global citizen, and genuinely kind human being, Lindners fieldwork and writing have produced remarkable insights, given rise to related efforts among a community of activists and scholars around the world, and inspired a journey that led to this book. I also wish to acknowledge my friend and colleague, Delphine Gras, for her encouragement, feedback, and generosity of spirit. Thank you.

AMERICAN

SHAME

INTRODUCTION

American Shame and the Boundaries of Belonging

Myra Mendible

Shame as Spectacle: Bodies That Matter

The spectacle is the acme of ideology, for in its full flower it exposes and manifests the impoverishment, enslavement and negation of real life.

Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle

On any given day in Americas twenty-four-hour news cycle, shame is a hot commodity. Stories and images of disgraced politicians and celebrities solicit our moral indignation, their misdeeds fueling a lucrative economy of shame and scandal. Nothing fosters the illusion of solidarity like shared condemnation: joining the chorus of outrage that follows the exposure of the rich and famous, we play out a fantasy of community that otherwise eludes us. Here is the stuff of cultural belonging todaya bonding ritual that fills in for the spectacles that once were town square stocks and pillories. Righteous rants about the latest breach in conduct circulate via chat rooms, blogs, and social media; civic interactivity plays out in tweets, hashtags, and posts. Duly disciplined, the exposed offender, egotist, or fool bolsters our faith in the notion that, in America, personal responsibility accounts for failures and everyoneeven the rich and famousget what they deserve.

But of course this is a comforting fiction. We watch as the disgraced politician goes on to profit from memoirs and reality show appearances; the chastened celebrity is rehabilitated and rebranded. Whereas the experience of shame prompts a desire to hide and conceal, shame spectacles generate publicity, increasing marketability and trending stats. They garner photo-ops, TV appearances, feature stories, press releases, andmost enthrallingstaged mea culpas. As spectators, we play our part in these charades, expressing our outrage in shrill tirades, all Sturm und Drang and grand gestures. Commodified and converted into spectacle, shame is more entertaining than disciplinary, more akin to a system of sociality than morality. It produces tabloid fodder for mass consumptiona carnival of moral outrage that channels a peoples discontent but ultimately deflects attention from the embodied conditions where shame does its work. Instead, we are induced to speak of shame as an absence, to behold it in its undoing. Performing a trifling dance in public, shame becomes form emptied of content, a kind of holographic image projected on bodies that matter enough to be singled out for media attention.

We are so acculturated to shame as spectacle that its power is often overshadowed by its trivialization. In the logic of abstract exchange that dominates market cultures, spectacle reflects the commoditys complete colonization of social life. Relevant here is how these interactions deflect attention from the self and toward its objects: shame in this context has nothing to do with our own behaviors or flaws. It remains safely detacheda story we tell about them.

As I write this, the internet is alight with another celebrity shame spectaclethe so-called slut shaming prompted by Miley Cyruss lewd onstage twerking at the MTV 2013 Music Video Awards. Moral indignation at Mileys behavior is the flavor of the month: Shame on you, Miley videos have popped up on YouTube, the online magazine Celebuzz has declared it the twerk heard round the world, and there have been numerous complaints to the FCC (which does not have the authority to sanction cable networks). Twitter has announced that Mileys performance set a record on the social networking site, garnering 306,100 tweets per minute.

Shame as commodity spectacle is most productive (and profitable) when projected on media-worthy objects, on bodies that matter enough to merit attention. In an American society where the success ethic predominates, achievement measures our intrinsic worth. This involves, in part, attention to the ways that human dignity is eroded by biopolitical processes that are naturalized and familiarized to the point that they are made invisible.

Shame calls out for a witness. The elderly woman who must water down her soup may be socialized to endure her shame in private, but its public disclosure bears acknowledgment, registers what Sara Ahmed has called the sociality of pain. As witnesses to anothers experience of shame, we grant it the status of an event, endowing it with a life outside the fragile borders of [the others] body. But when the face is absent, ethical foundations become less stable. Denying the others longing for recognition and place, we deny his very existence. The others shamewritten in her facial features and body language, signals her self-consciousness: a testament to their humanity. Although this affirmation may not be authorized or acknowledged on the structural levelthrough institutions and social practicesit nonetheless registers at the level of affect. This is one reason that prejudice and hostility between different groups tend to decrease when groups interact often and why political leaders who aim to incite violence between rivals first segregate target groups, denigrating and humiliating them out of sight, erecting walls between them (literal and symbolic) so as to avoid reminders of their humanity. Jews were restricted to ghettoes; Blacks, to separate schools and neighborhoods; Native Americans, to reservations. These were locations where their shame and humiliationeven extinctioncould remain on the periphery of social consciousness. It is one thing to ignore anothers suffering when it occurs out of sight or is deferred through representation so that it remains

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.