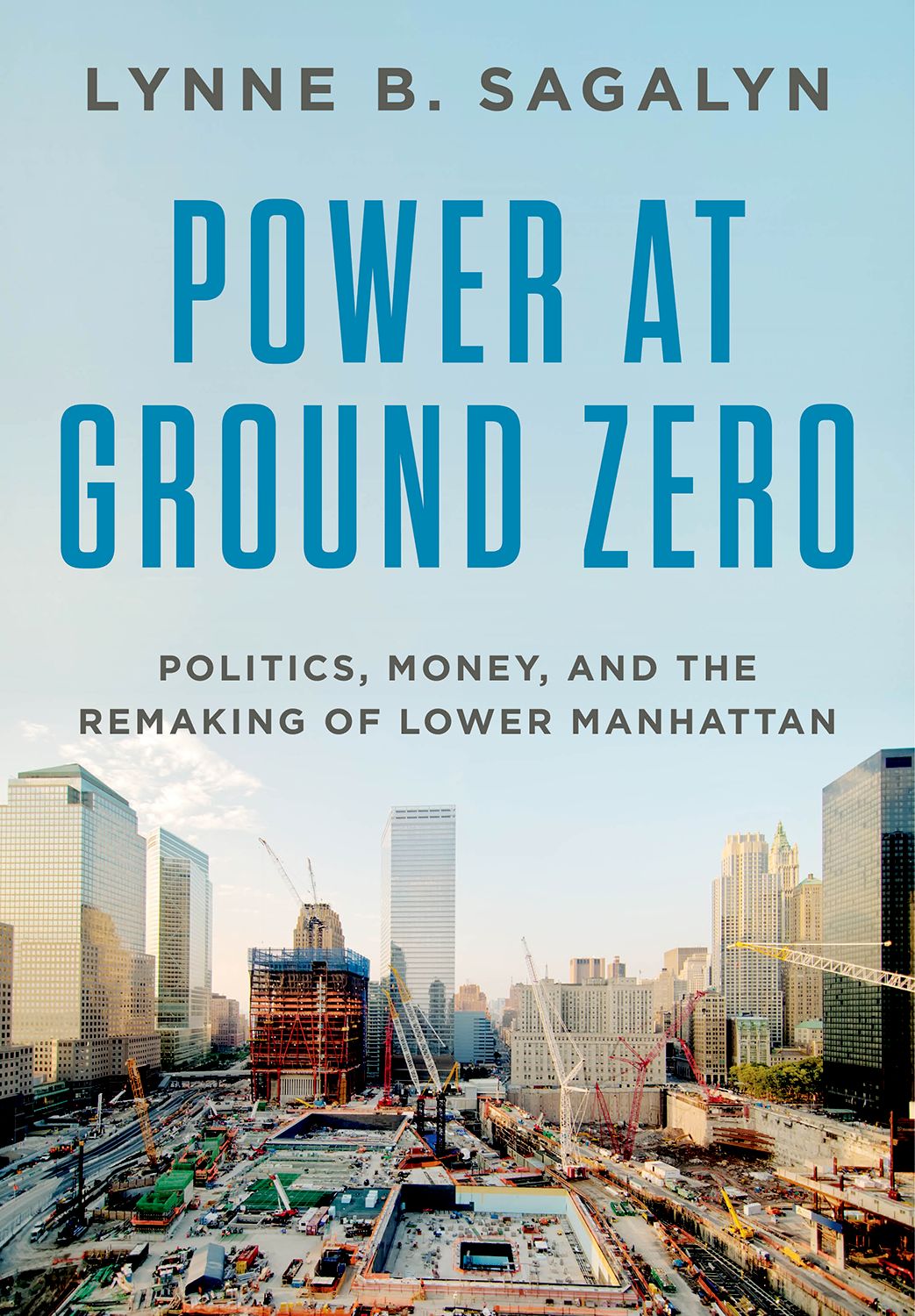

Power at Ground Zero

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Lynne B. Sagalyn 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sagalyn, Lynne B., author.

Title: Power at ground zero : politics, money, and the remaking of lower Manhattan / Lynne B. Sagalyn.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016009574 (print) | LCCN 2016027366 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190607029 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190607036 (E-book) |

ISBN 9780190607043 (E-book)

Subjects: LCSH: September 11 Terrorist Attacks, 2001. | Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)History21st century. | City planningNew York (State) | Land use, UrbanNew York (State) | Public buildingsNew York (State)Design and construction. | Economic assistanceNew York (State)New York. |

BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Sociology / Urban. | ARCHITECTURE / Urban & Land Use Planning. | ARCHITECTURE / General.

Classification: LCC HV6432.7.S224 2016 (print) | LCC HV6432.7 (ebook) | DDC 974.7/1044dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016009574

Figures 1.5, 1.8, 8.3, 8.4, 9.3, 11.11, 12.4, and color plates 12 and 19 are from the New York Times (issue and year information in caption). All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of the Content without express written permission is prohibited.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For all who worked to rebuild Ground Zero and the citizens of the City of New York

Contents

On September 21, 2006, Governor George E. Pataki of New York and Governor Jon S. Corzine of New Jersey with Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg of New York City gathered at Ground Zero for a hastily called celebratory news conference to announce that the Board of Directors of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey had approved a series of agreements expected to expedite the redevelopment process. The time has come to build this, said the Port Authoritys chairman, Anthony R. Coscia. The agreements set forth the most definitive blueprint to date after years of conflict and contention over every piece of the master plan for rebuilding the sixteen acres at Ground Zero. The moment marked a watershed. The process of getting to this point had not been easy. It followed months of negotiations among the three government stakeholders and real estate developer Larry A. Silverstein, acting as general manager of his investment partnerships ninety-nine-year lease on the World Trade Center sitestill a holenegotiations that could only be described as difficult, disputatious, and at times ugly. Money was the fundamental sticking point. The Global Realignment, as the new deal was called, redefined who would build what on the site, dividing control over the development rights for the commercial program between Silverstein and the Port Authority, owner of the land on which the World Trade Center complex had been built in the 1960s. Silversteins role was reduced to building three of the five planned towers, though he emerged with the three best development sites from a real estate perspective. The Port Authority would build the Freedom Tower, an uneconomical political statement promoted by Pataki, as well as a fifth office tower and the retail component of the plan. The bi-state agency remained responsible for building out the complex underground infrastructure, which had to be accomplished before construction could start on any other part of the rebuild, including the memorial and the Memorial Museum. Just six weeks before the 9/11 attack, the Port Authority had sold a long-term interest in the World Trade Center complex to Silverstein in a much-heralded historic transaction that transferred ownership of the iconic complex to private investors. With the 2006 deal, the Port Authority was back in the real estate business. From the first day forward after 9/11, the words used by all stakeholders to describe the rebuilding effort were framed in patriotic meaning and heartfelt commitment to the losses of 9/11words that spoke to its symbolic mandates.

The driving forces at work in rebuilding Ground Zerocivic purpose, political opportunity, and commercial gainmirrored both the optimism of recovery and the rough-and-tumble politics of power in New York City. These forces would define the constellation of issues swirling about the site for many more years to come until visible progress above ground began to give shape to a new district in lower Manhattan. The realignments of the 2006 deal created modest confidence in the task of rebuilding among the stakeholders standing in the open air around the podium on a blue-skies day whose clarity was all too reminiscent of the day two hijacked planes rammed into the twin towers. On both sides scars remained. And wariness. The difficulties in coming to terms on these agreements did not stop with the board vote but continued for ninety minutes afterward, with both parties engaging in last-minute wrangling, according to the Times. The announcement of the news conference just minutes before it started gave the media little time to get there. This semisecret aspect of the event turned out to be a portent of rough times ahead, as relations between the public agency developer and the private-sector developer of Ground Zero remained strained by lack of trust and a misalignment of interests.

Several years of high-profile debates about architectural vision and fierce battles between dueling designers had galvanized public attention. These were now settled. The program for memorializing the losses of 9/11 was in place. The actual work of rebuilding lay ahead, in the complicated challenge of figuring out how to turn ambitious vision into tangible reality. The stakes of succeeding were of psychological as well as economic importance to the city at large and its region and the country.

After the big design decisions had been made, it seemed possible to conclude that the task of executing the plans was not newsworthythat is, not much different from a conventional, albeit, large development projectuntil controversy threatened to reopen those already-made decisions or propelled elected officials into outrage and open conflict. Though seemingly mundane and less newsworthy, the task of reconciling aspirations with economic reality was paramount. It impacted everything at Ground Zero: how the 9/11 Memorial would be experienced and how the Trade Center site would meld with the urban fabric of adjacent neighborhoods. It would shape the experience of commuters and shoppers traveling through the Transportation Hub. Most critically from the perspective of state and local officials, it would determine when the new towers at Ground Zero would repopulate the skyline of lower Manhattan and with what level of public financial support to assure that they do. In short, for years a lot was happening to shape decisions at Ground Zero that often did not make headline news and that most people could not learn about.