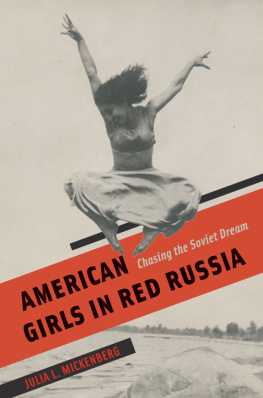

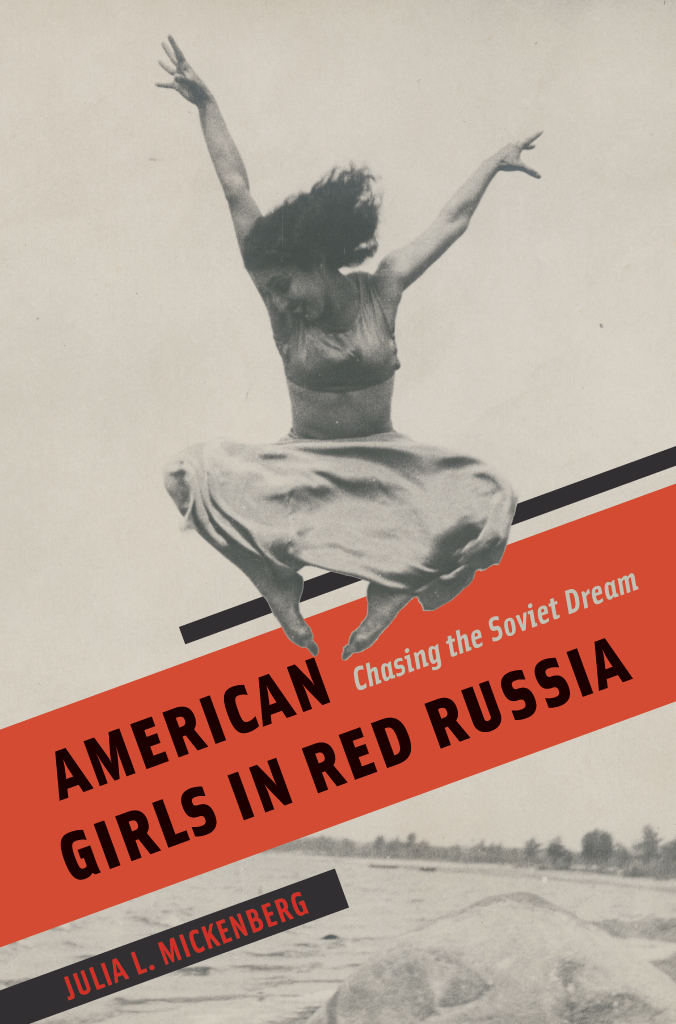

American Girls in Red Russia

Chasing the Soviet Dream

Julia L. Mickenberg

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by Julia L. Mickenberg

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-25612-2 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-25626-9 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226256269.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mickenberg, Julia L., author.

Title: American girls in red Russia : chasing the Soviet dream / Julia L. Mickenberg.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016041702 | ISBN 9780226256122 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226256269 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: AmericansSoviet UnionHistory. | WomenUnited StatesHistory20th century. | WomenSoviet UnionHistory. | Women and socialismSoviet Union. | FeminismSoviet Union.

Classification: LCC DK34.A45 M54 2017 | DDC 305.420947dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016041702

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Edie, who has lived with this book her entire life.

And for Dan, who made everything possible.

Contents

American Girls in Red Russia

By spring 1932, the American girls in red Russia had begun to attract notice:

Armed with lipstick and toothbrush, and with an insatiable lust for the bizarre and exciting, American girls have been invading Moscow. Two hundred strong and more, chic, smart young women have come barging into the Red capital, some lending the boys and girls a hand in building Socialism, others seeking husbands among the lonely American engineers, or romantic young Russians, always ready to pay homage to the glamorous American girl. Stenographers, nurses, dancers, painters, teachers, sculptors and writersserious maidens, determined to take part in the new life that is growing so swiftly. Pauline Emmett, a tall, robust lass from Illinois, fled from the social whirl and chose instead the Soviet frontier, where she edits a magazine for American workers and swings a pick and shovel when shes called for social work. Fay Gillis, Brooklyn aviatrix, is hoping to fly for the Soviets. Jeanya Marling, barefoot dancer and raw

Fig. 0.1 Milly Bennett, American Girls in Red Russia, EveryWeek, May 2829, 1932, Milly Bennett papers, Hoover Library, Stanford University.

This breezy description is slightly adapted from a syndicated 1932 news article by Milly Bennett, a divorced journalist from San Francisco, and one among the legions of American women drawn to the Soviet Union in the early 1930s. Shed arrived less than two years earlier to accept a staff position on the Moscow News, the Soviet Unions first English-language newspaper, which journalist Anna Louise Strong started in 1930. Bennett and the women she describes were part of a now-forgotten trend.

We dont usually think of Moscow as a popular destination for American women in the early twentieth century. A mythology surrounds the lost generation of Americans who sought out Paris in the 1920s, but few know about the exodus of thousands of Americansformer Paris expats among themto the red Jerusalem not long after that. And while most Americans greeted the Bolshevik revolution with skepticism and even fear, a large swath of activists, idealists, and cultural arbiters, many feminists among them, had a very different reaction.

Well past the end of the Cold War, it has remained difficult to come to terms with what in the 1920s and 1930s amounted to nearly ubiquitous attention to the Soviet Union among reformers, intellectuals, and members of the artistic avant-garde. We have forgotten both the daring spirit of the new woman and the widespread interest in the Soviet experiment.

Along with legions of American girls who are now forgotten, revolutionary Russia attracted many of the countrys most distinguished women, among them fiery orators and free love advocates like Emma These women and many others traveled to the new Russia, or devoted years of their lives to it from afar. From even before the Bolshevik revolution, women in the United States looked toward Russia for female role models.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, the new womanhair upswept, demeanor purposeful, sights set on paid or creative work, social reforms, or causes like free speech, free expression, or free lovebecame a familiar figure on the streets of US and European cities and in fiction, art, and advertising. And she came to embody the promise and perils of modernity. Until the end of World War II, Russia and the Soviet Union helped American new women envision themselves, society, and possibilities for the future. Such women, in turn, played an important role in shaping their compatriots image of Russia.

This chapter in American womens history highlights themes basic to the development of Western feminist thought, ideas about citizenship,

The story of American new women and the new Russia has been as much repressed as forgotten. As the horrors of Stalinism became undeniable, both the romance of revolutionary Russia itself and the utopian imagination driving that romance were cast as nave, irrational, embarrassing, even dangerous. In Assignment in Utopia, journalist Eugene Lyons described a range of witless female pilgrims who were easy targets for Soviet propaganda: Virginal school teachers and sex-starved wives came close to the masses, especially the male classes, and some of them were so impressed with the potency of Bolshevik ideas that they extended their visas again and again. A few of them emerged to write shrill books about the Soviet Unions new unshackled attitudes, the equality of the sexes, abortion clinics. For Lyons, descriptions of Western women in Moscow functioned primarily as a vehicle for dismissing everyone caught up in the romance of red Russia.

During and even before the Cold War, repentant communists reports cast a dark shadow over what Vivian Gornick has called the romance of American communism, especially as that romance was tangled up in the Soviet Union. By the late 1940s, most Americans saw the Soviet Union as an evil empire, and those who once expressed enthusiasm for the Soviet experiment either recanted or kept quiet about it. By the logic of the Cold War that came after, such enthusiasm reflected badly on suffragists, reformers, journalists, and creative workers whom some might otherwise wish to hold up as models. But this narrative of disenchantment clouds our ability to understand the enchantment itself: the real depth of interest, hope, and fascination that the Soviet Union represented for many people, even when those feelings were mixed with a sense of the gap between Soviet realities and ideals.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).