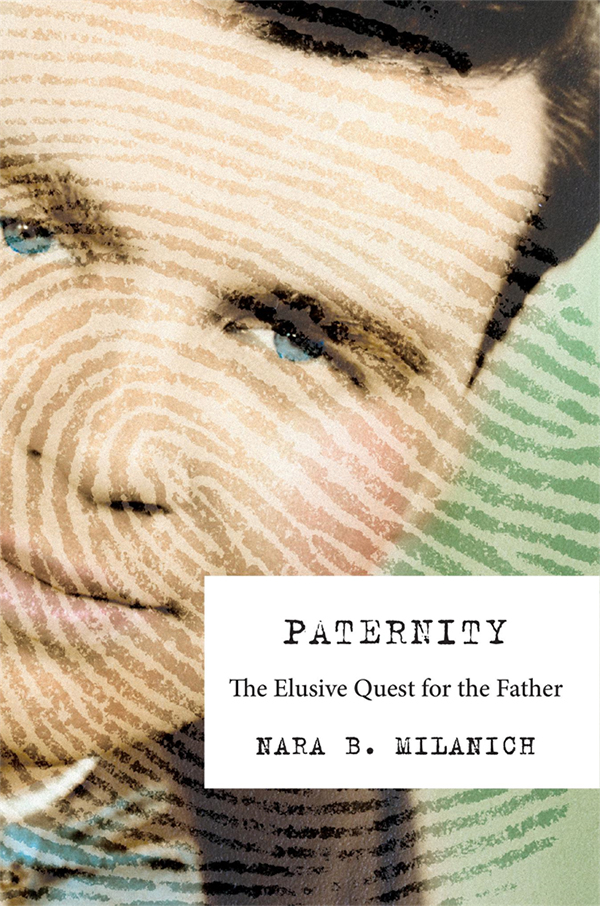

NARA B. MILANICH

Jacket art: Thumb print (Michael Burrell/Getty Images) superimposed over photograph (Kirn Vintage Stock/Getty Images).

9780674980686 (alk. paper)

Names: Milanich, Nara B., 1972 author.

Title: Paternity : the elusive quest for the father / Nara B. Milanich.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: LCSH: Paternity testing. | Paternity. | FatherhoodSocial aspects.

It is hard to grasp, given the immense and visible parcel in which man-made history has packaged the idea of paternity, that paternity is in fact an abstract idea.

Mary OBrien, The Politics of Reproduction, 1981, p. 29

THE PROTAGONISTS OF THE courtroom drama consisted of a young mother, a putative father, and an adorable red-haired baby. In the early 1940s, as war raged abroad, the inquest unfolded in a packed Los Angeles courtroom. This was not just any paternity suit. The mother was Joan Berry, a twenty-three-year-old aspiring actress; the baby, her daughter Carol Ann; and the accused father Charlie Chaplin, Hollywood celebrity.

Berry was Chaplins onetime protg, and in happier times, the two had read Shakespeare together and practiced drama. Now the fifty-four-year-old actor, whose penchant for much younger women was well known, stood accused of fathering Berrys baby. He admitted the romance but vehemently denied the paternity charge. A week after the case broke, the actor wed his fourth wife, the eighteen-year-old daughter of playwright Eugene ONeill. Thanks to his British citizenship and leftist political leanings, Chaplins ideological proclivities were for some sectors of the American public as questionable as his romantic ones. For her part, Berry was portrayed as a hapless ingnue, aflame with the glamour of Hollywood, possibly mentally unstable, pretty to the eye, but, by her own lawyers account, of limited intelligence.

But it was the baby who was the star of the show. Not yet born when the suit over her paternity was filed, over the course of the saga Carol Ann blossomed into an amiable toddler. She was a courtroom fixture, sitting on the wooden table in front of her mothers lawyer. The press gleefully reported on her colorful pinafores and penchant for patty-cake. Still, the legal proceedings were serious business. At stake was the identity of a child. Would she face a life of penury or comfort? Would she have a name, a patrimony, a father? The paternity suit, her mothers lawyer declared and the newspapers would repeat, was the babys day in court.

The drama featured other players, too: witnesses like Chaplins handyman and butler, who testified about the couples trysts; and the members of the jury, ordinary women and menhousewives, an interior decorator, a retired property managerwho arrived in court carefully coiffed in anticipation of the cameras. There was Berrys attorney, himself something of a courtroom thespian, who in an especially memorable three-hour closing statement denounced the actor as a cheap cockney cad and a lecherous hound. (Chaplins own lawyer responded by comparing his client to Christ crucified on the cross.) Finally, there were the newspapermen, and a few newspaperwomen, who breathlessly broadcast the story to the public. Their daily reports from the courtroom included descriptions of the protagonists outfits (Joans chartreuse coat) and moods (Charlies grimaces). The heady spectacle of sex, celebrity, and scandal not only reached American readers but, thanks to the global wire services, was beamed out to a world at war.

The two-year inquest had numerous twists and turns. In a related criminal charge, Chaplin was tried and acquitted of trafficking Berry across state lines for immoral purposes. He briefly faced deportation charges as an alien. As for the proceedings concerning Carol Anns paternity, the first suit ended in a mistrial when the jury deadlocked, and a new trial was called. The ChaplinBerry saga had begun as President Roosevelt ordered striking coal miners back to wartime production and Allied troops amassed in the Mediterranean readying to invade Italy. By the time it ended, Roosevelt was dead and the Allied victory in Europe was weeks away. Yet for all its protracted drama, the case is a simple one, the judge reminded the courtroom as the proceedings drew to a close. It revolved around one question: Is the defendant the father?

His question was less simple than it appeared. Paternity is a question of long-standing cultural, legal, political, and scientific interest and, according to a long Western tradition, an intractable one. Whereas a mothers identity can be known by the fact of birth, the father has always been maddeningly uncertain. The quest to identify him animated medical experts at least since Hippocrates and preoccupied jurists of Roman, Islamic, and Jewish law. Literary fathers have brooded over their paternity in the works of Homer and Shakespeare, Hardy and Machado de Assis. Theorists from Friedrich Engels to Sigmund Freud posited paternal uncertainty as a primordial foundation of human society and the human psyche. For a generation of early-twentieth-century anthropologists, cross-cultural beliefs about paternity were the most exciting and controversial issue in the comparative science of man.

But paternity is not just a subject of intellectual rumination. As the ChaplinBerry inquest suggests, it matters to men and women, to children and families, for reasons that are patrimonial, practical, and existential. Questions of paternity have historically arisen in the context of disputes over child support and inheritance. The orphaned and the adopted have asked this question in relation to lost identities. More recently, assisted reproductive technologiesgamete donation, surrogacyhave raised old issues in new ways.

Paternitys stakes are public as well as private: they matter to states and societies and not just individuals. This is why the dispute over Carol Anns father took place in a courtroom and was governed by rules set by law. For while kinship is often seen as a pre-modern or non-Western form of association, it is at the heart of modern social and economic citizenship and a key symbol demarcating public and private spheres. Family ties are important to states because they confer access to war pensions and social security, to nationality and the right of noncitizens to settle in a country. Historically, children bereft of kin ties have become public charges. The question of the father raises questions about the balance of rights and responsibilities between individuals and societies.