Nadel - Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon

Here you can read online Nadel - Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Iowa City, year: 1991, publisher: University of Iowa Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nadel: author's other books

Who wrote Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

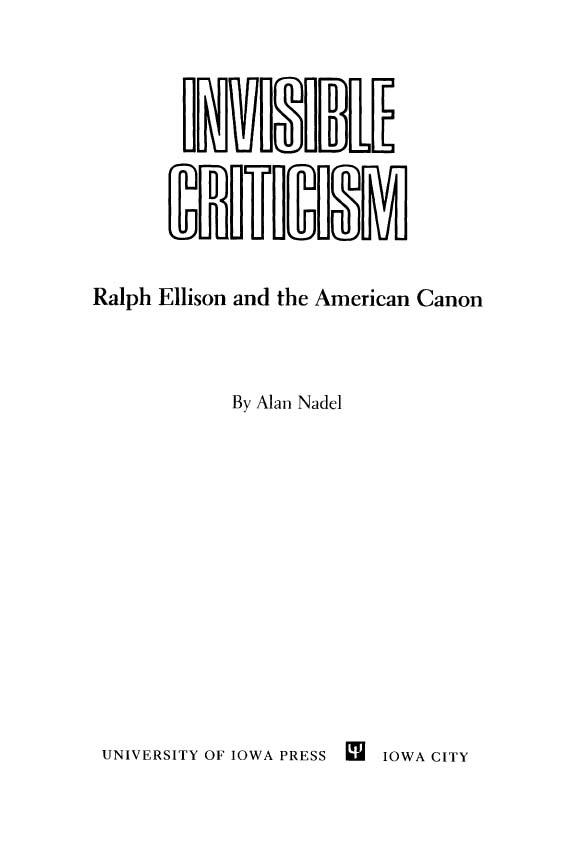

INVISIBLE CRITICISM

University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242

Copyright 1988 by the University of Iowa

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First paperback printing, 1991

Typesetting by G & S Typesetters, Austin, Texas

Printing and binding by BookCrafters, Chelsea, Michigan

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nadel, Alan, 1947

Invisible criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American canon /

by Alan Nadel.1st ed.

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-87745-190-7, ISBN 0-87745-321-7 (pbk.)

1. Ellison, Ralph. Invisible man. 2. Canon (Literature).

1. Title.

PS3555.L62515358 1988 | 87-25071 |

813.54dc19 | CIP |

Dedicated to my wife, Amy Perkins,

and my son, Alexander Percy Nadel,

who love words.

Contents

I t goes a long way back, some twenty years. Thus begins of Invisible Man, and thus begins this book on Invisible Man, which is being published almost twenty years to the day from the time I wrote, as an undergraduate at Brooklyn College, my first words on Ellisons novel. The assignment was to compare two books, at least one of which had to appear in the syllabus, that is, the canon. The canonized text I chose was Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Because I was poor and for the preceding couple of years had been more or less self-supporting, I chose the second book from a small paperback library I had accumulated two summers earlier, when I worked at near-minimum wage in a book warehouse near the Red Hook docks. It was a place in many ways not unlikeat least as I imagine itInvisible Mans Long Island City paint factory. Each day just before closing I would duck behind the stacks and slip a book under my shirt. Thus I was first exposed to an array of writers, including Sartre, Moravia, and Ellison.

At the time I wrote that undergraduate comparison between Ellisons work and Twains, I was primarily concerned that the paper was overdue and, equally, that its completion would bring me that much closer to graduation and therefore to the draft. My literary concerns were secondary; I was wholly ignorant, moreover, of the issues of canonicity, historicity, and cultural criticism this fortuitous comparison suggested. I soon became very aware, however, that many similarities existed between the textsallusions and swerveswhich no one else seemed to have noticed. I had never seen the word hermeneutics, but I knew some encoded relationship was present; I had never heard of intertextuality, but I knew that in some way the meaning of the text at hand depended greatly on its relationship to other texts with which it had not been commonly grouped; I had never considered the concept of rehistoricism, but I knew Ellisons book was pointing toward some gap, some omission, some blindness in the way we read the past or wrote about it. Or at least I think I knew these things, at some level, as I tried to fathom the uncanny resonance I found between two American novels. Perhaps I just dreamed that I knew those things.

If so, as the invisible mans last sentences in say, it was a dream I was to remember and dream again for many years after. But at the time I had no insight into its meaning. First I had to attend college (or, in my case, graduate school). As my reading broadened, I found myself returning periodically, with ever-increasing insight, to Invisible Man and, through Invisible Man, to American literature and American studies. For this I am indebted to Ralph Ellisons prophetic novel. Frequently I was also struck with the sense that I had seen something no one else had. Or if others had seen what I had, they had not understood. Or if they had understood, they were not saying so. Or perhaps I was dreaming. I am indebted, therefore, to Ralph Ellison himself, who read an earlier version of my manuscript and responded with an invaluably generous letter convincing me that, like my original term paper, this work on Invisible Man was long overdue.

Gratitude goes also to Vincent Leitch, who helped me sharpen the Introduction; Carolyn Karcher, who gave advice on some aspects of ; Donald Gibson, who supervised my dissertation on Ellison; Carol Smith, who was the second reader; and Paul Fussell, who not only read the work with wit and dispatch but also has had, in more general ways, a profound effect on my education. Of course, as Huck might add, I dont blame him none, he didnt mean no harm by it.

Finally, I owe the most intangible debt to my wife, Amy, without whom, for reasons that transcend logic and doubt, this book would not have been.

I n recent years, the issue of canon formation has attracted a great deal of attention, a phenomenon not incidental to the influence on literary study of poststructuralism, feminism, and ethnic consciousness. At the risk of oversimplifying, we could say that these approaches mandate modes of thinking which urge distance and skepticism, modes which actively call into question the implicit assumptions of any enterprise or institution, and which actively seek to determine the presence and nature of hierarchies. Applying such modes of investigation to the realm of literature makes it hard to take for granted the great authority canons have wielded over the last century. When we look at the hierarchies in literary criticism, at the value systems those hierarchies encode, at the people and institutions they empower, and at the others they marginalize, it becomes difficult to view texts as reflecting (or failing to reflect) absolute value from an absolute source. Even the field from which the canonized texts emerge cannot be seen as a totality, either in potential or in fact. Rather, that field exists already in a privileged position created by a series of prior cuts and hierarchies.

Since these prior cuts, moreover, determine at very basic levels the power to speak, to be heard, and to be understood, they in fact control not only what constitutes a canon but also what may affect it. The obvious problem, then, is not that there are no channels for change but that those channels become dysfunctional when they themselves need alteration. To put it another waya way that parallels the situation of Ralph Ellisons protagonisthow can one be an effective spokesman for change, when speaking effectively means conforming to the very set of rules one wants to change? As that protagonist discovers, this problem exists whether speech means speaking at a ceremonial dinner of white citizens or before a northern trustee, in the office of a black educational leader or a white businessman, at a public political rally or a private committee meeting. As any structuralist would point out, the speech cannot have meaning independent of a complicated system of social, psychological, and linguistic hierarchies. As any poststructuralist would further note, those hierarchies reflect an arbitrary and tenuous center, thoroughly and always dependent on an already present but unacknowledged other whose crucial presence can only be perceived as absence, as its own invisibility.

The problem, then, of speaking from invisibility, of making the absence visible, pertains not only to public functions but to speech itself, to that act, always both autobiographical and fictional, of describing ones world. Ellison demonstrates this memorably when his invisible and nameless narrator speaks to an invisible and nameless audience, attempting to uncover in their shared otherness the voice which had been encoded into silence, excised from the canon. A first and central claim of my book, therefore, is that

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon»

Look at similar books to Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Invisible Criticism: Ralph Ellison and the American Canon and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.