UNREAL

CITY

ALSO BY JUDITH NIES

Native American History: A Chronology (1996)

Nine Women: Portraits from the American Radical Tradition (2002)

The Girl I Left Behind: A Personal History of the 1960s (2009)

Copyright 2014 by Judith Nies.

Published by Nation Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY 10003

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and the Perseus Books Group.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address the Perseus Books Group, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Nation Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail .

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nies, Judith, 1941

Las Vegas, Black Mesa, and the fate of the West / Judith Nies.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56858-487-4 (e-book)

1. Southwest, NewHistory20th century. 2. Las Vegas (Nev.)History20th century. 3. Coal mines and miningSouthwest, NewPolitical aspects. 4. Black Mesa (Navajo County and Apache County, Ariz.)History20th century. 5. Indians of North AmericaArizonaBlack Mesa (Navajo County and Apache County)Social conditions20th century. 6. Coal mines and miningSouthwest, NewHistory20th century. I. Title.

F787.N54 2014

979.3135dc23

2013048336

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of Roberta Blackgoat (19162002)

This extreme reliance on federal money, so seemingly at odds

with the emphasis on unfettered individualism that constitutes

the local core belief, was a pattern set early on.

Joan Didion, Where I Was From

In 1492 the natives discovered they were Indians;

They discovered they lived in America;

They discovered they were naked;

They discovered there was sin.

Eduardo Galeano, Children of the Days

CONTENTS

In 1982 Robert Redford starred in a modern cowboy western called The Electric Horseman. Set in Las Vegas in the early 1980s, the story was about a former national rodeo championand current alcoholicwho made his living pitching cereal as a breakfast of champions for a giant American food conglomerate. The corporation merchandised his former glory by sending him out into rodeo arenas mounted on a beautiful horse, both cowboy and horse trimmed in glowing electric lights. Often too drunk to remain upright on his horse, the electric horseman in the saddle was frequently a cowboy double substituted by the corporation.

Then, in one existential moment in a Las Vegas ballroom, the cowboy (Redford) decided he had been a commodity long enough and rode the horse off the stage, out through the endless corridors of casino slot machines, down the Las Vegas Strip, and into the magnificent wilderness of Nevadas purple mountains. The movie had all the elegiac themes of the contemporary American West: soulless corporations, feckless media in the character of Jane Fonda as a television reporter, the symbolic lone cowboy striking out on his own, and the transformative power of western spaces. The movie was a huge success.

About the same time the film was in the theaters, a man named Leon Bergernot a household namehad his own existential moment. As director of the Indian Relocation Commission located on East Birch Street in Flagstaff, Arizona, he resigned from his job with a public statement of shocking clarity: he called the congressionally mandated relocation of ten thousand Navajo people the equivalent of American genocide. Berger, who had once worked for Senator Barry Goldwater, was an unlikely rebel.

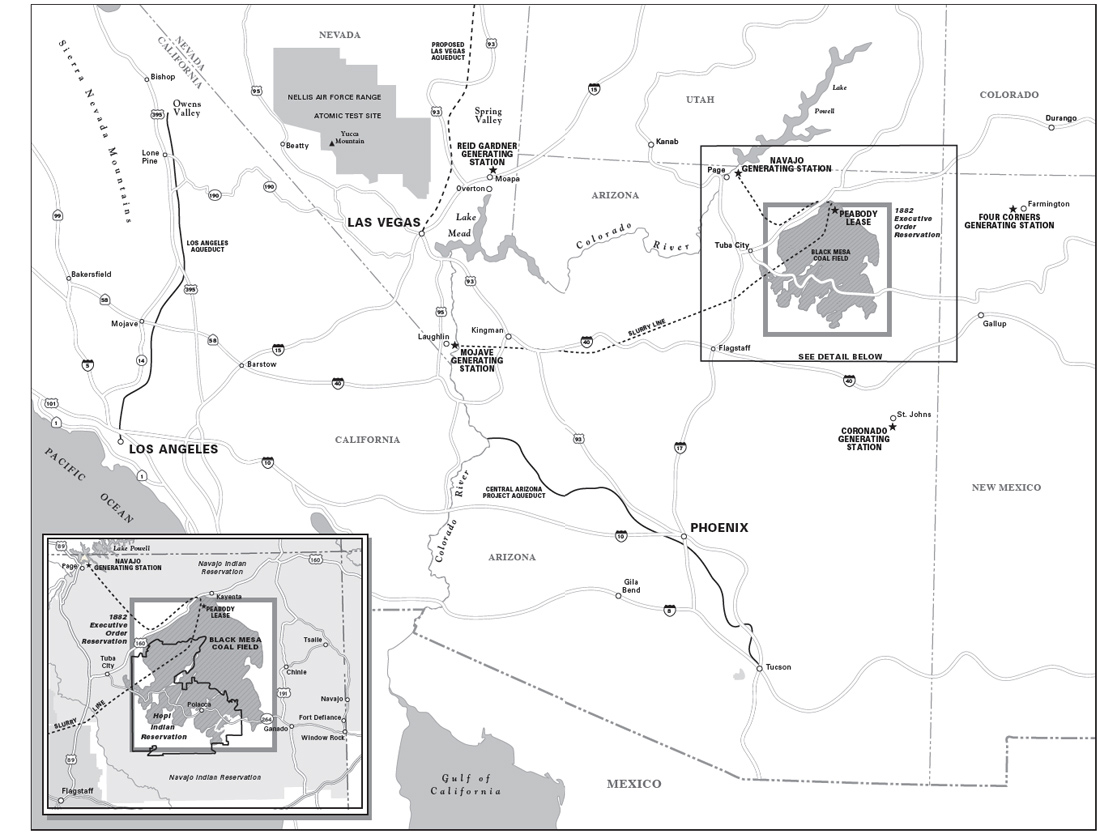

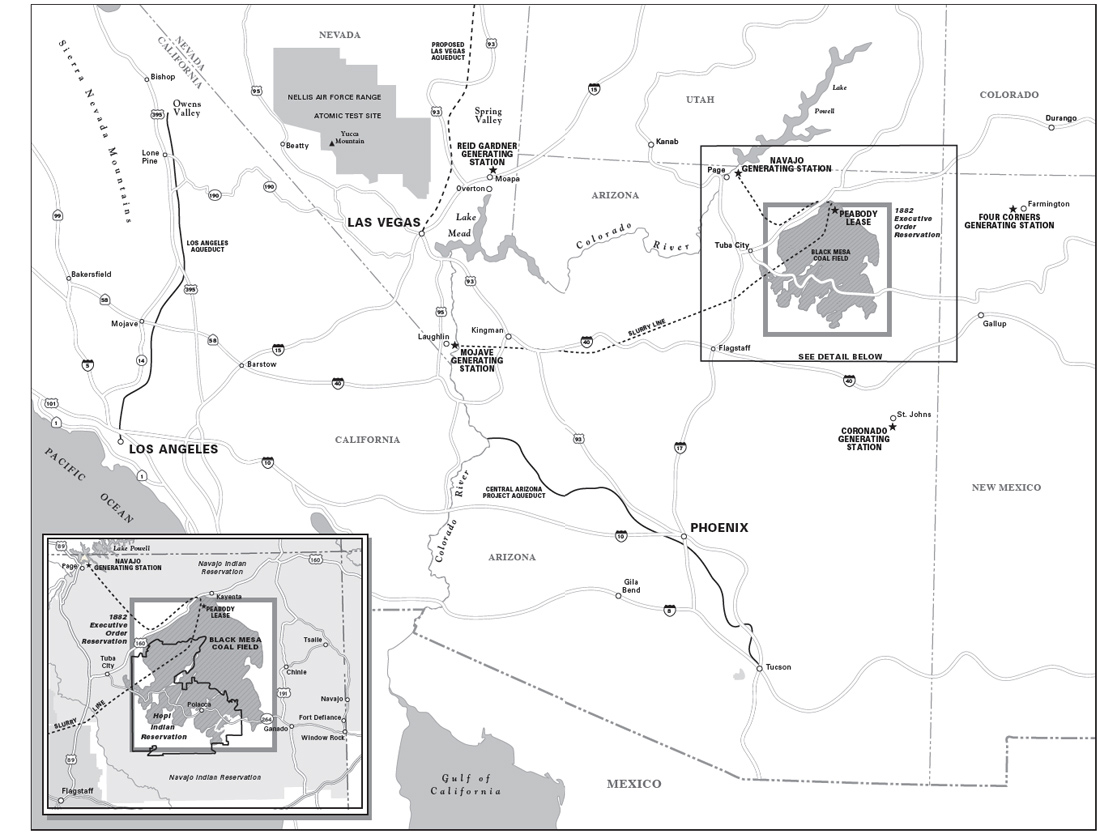

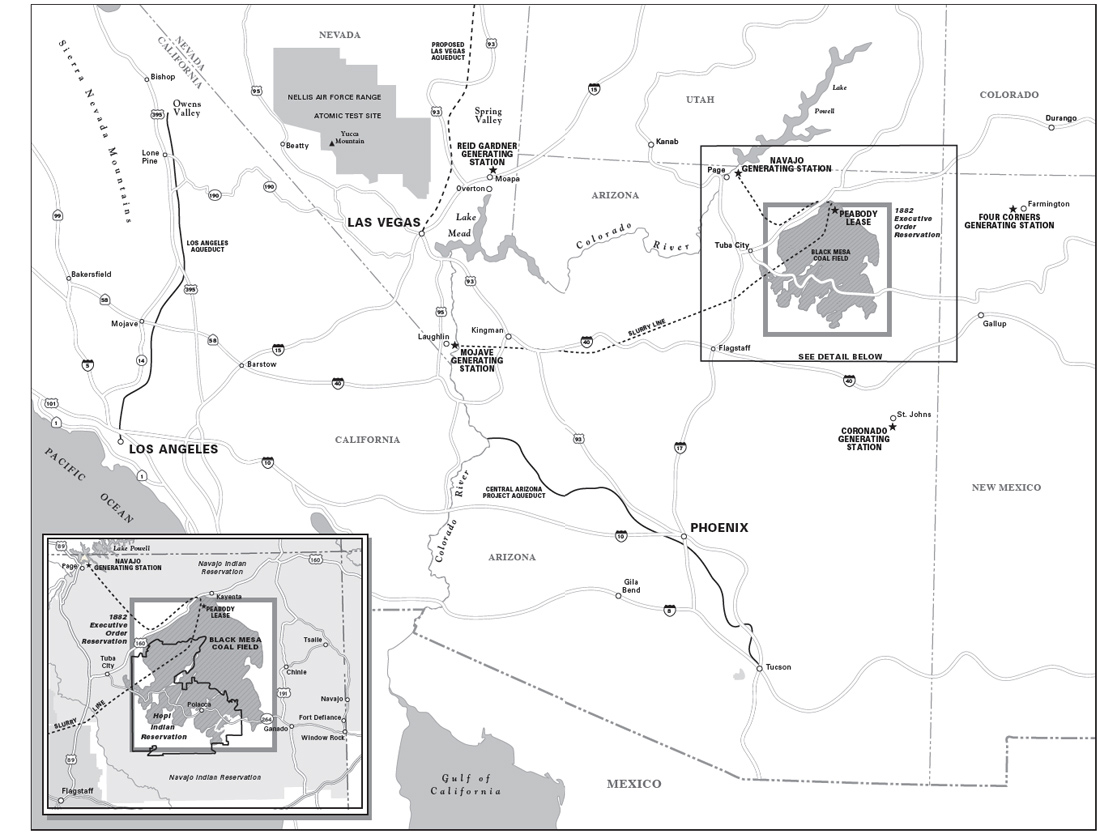

Thousands of Navajo families were being expelled from a 4,000-square-mile reservation that was jointly occupied by the Navajo and Hopi Indians. Located some 150 miles northeast of Flagstaff and ending some 25 miles before Monument Valley, the entire reservation was known legally as the Executive Order Reservation of 1882 and geographically as Black Mesa. In 1974 Congress passed a poorly conceived bill that divided the surface of the Executive Order Reservation on a fifty-fifty basis between the two tribes. As a practical matter, only a handful of Hopi, who lived clustered in villages at the rocky edge, were affected, but thousands of Navajo families, who lived in sheepherding camps spread out in the interior, had to be moved. Black Mesa was so isolated it was not mapped in the grid system of the US Geological Survey until late in the twentieth century.

Berger had been handpicked to direct the commission. But as the man charged with removing thousands of Navajo families from the newly delineated Hopi lands, he was no longer able to ignore the realities of an impossible job. For one thing, no one had ever accurately counted the number of Navajo to be moved; for another, no planning had been done to buy alternative land or provide social services or build housing to relocate them; and finally, the Navajo relocation marked the first time in a hundred years that a boundary issue between two tribes was being settled by removing uncounted thousands of the opposing tribe. Why hadnt the usual arrangement of alternative public lands and a financial settlement been worked out as compensation? This last was a question no one seemed able to answer, especially since that was the solution already in motion to compensate the Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine who otherwise might have requested the removal of many prominent Boston and Philadelphia families from their ocean-front property on the Maine coast.

Bergers incendiary resignation brought unwanted publicity to certain complex details that had theretofore remained invisible. As it turned out, those same disputed Navajo-Hopi lands contained the largest untouched coal deposit in the country. Black Mesa was made of coal. Mapped and measured by the Arizona Bureau of Mines, the Black Mesa Coal Field lay entirely beneath the Hopi-Navajo lands and held more than 21 billion tons of valuable low-sulfur coal. (The Black Mesa Field, said the

Next page