Often a writer is queried as to the source of an idea. Ordinarily it is an impossible question to answer. But in this case lies an exception. Whatever ones opinion of upstart Los Angelesand there are manythere is no arguing that it stands as a major population center of the world, along with the likes of Tokyo, Mexico City, Rome, New York, Cairo, Delhi, or Beijing. But for a moment try to comprehend that one individual could be given credit for the existence of any of those cities named. If such a concept is intriguing, then one might wish to read on.

When this writer first ventured to Southern California, it was from a dimly lit existence in southeastern Ohio. There were hills there on the fringes of Appalachia, but they overlooked for the most part only other hills. And at night, there was little to be seen from any ridge but an endless expanse of ruffled indigo.

Imagine then, a young man fresh from the sticks being driven along the spine of the Hollywood Hills as the sun sinks into the Pacific to the south and dusk sweeps across the San Fernando Valley to the north. At a turnout off a narrow road as winding as any to a coal miners shack, standing beside a gas-guzzling sedan, engine off and pinging beneath the hood in the dark, the young man stares out across an endless valley paved with a carpet of lights that stretch to infinity. A real-life fairyland from this vantage point, and dont bother trying to tell him any different.

Whats the name of this road were on? the young man wants to know.

Mulholland Drive, his companion says. What do you care?

Just so I know how to get back here, the young man says, gaping at the view below. Whoever Mulholland was, he must have been important. Its one of the most amazing roads in the world.

IN SOME RESPECTS, of course, it is a fools errand, trying to excavate grandeur out of the past. Every day, thousands of people drive along or across Mulholland Drive, the familiar portion of which traces the crest of the Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles, all the way from the 405 Freeway to Highway 101. It is a way to get somewhere or a place to enjoy and the name is just something to plug into Mapquest or a smartphone. Who should think about William Mulholland? Why would anyone care?

Catherine Mulholland, granddaughter of the man, grappled with the matter in significant ways. In an unpublished bit of autobiography she remembers often being asked, Are you related to the highway?

And when I reply that it was named for my grandfather in 1925, the response ordinarily produces neither recognition nor much curiosity. In high school I sometimes longed for such indifference, because in the late 1930s, Mulholland Drive had become the foremost trysting, parking and necking spot in Los Angeles.

It turns out that William Mulholland was in fact the highest-paid public official in California a century or so ago, but by todays standards that doesnt mean muchthat grand annual salary wouldnt cover the mortgage payment on most of the homes along the road bearing his name today. In 1974, Robert Towne wrote the script for Chinatown, an acclaimed film that derives substance from some of the things Mulholland was involved with, but he is called Hollis Mulwray in the film, his fictional character is minor and killed early on, and the filmmakers had to fudge most of the actual factsincluding the time framefor fear audiences would get lost in the forests of history.

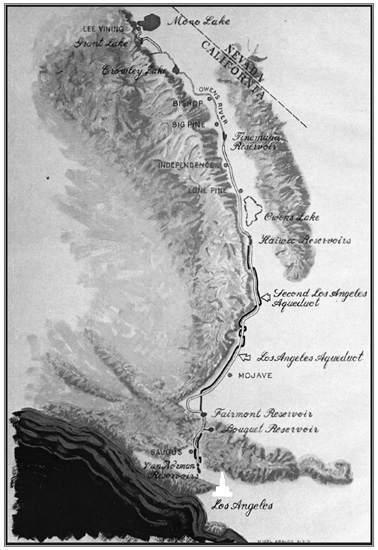

In the latter half of the twentieth century, a number of factually based works were written regarding the fierce water politics in the West, including Marc Reisners notable Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water (1993). Mulholland and the Los Angeles Aqueduct get their fair share of mention there and in other books, including William Kahrls exhaustive Water and Power: The Conflict over Los Angeles Water Supply in the Owens Valley (1983) and Abraham Hoffmans Vision or Villainy: Origins of the Owens ValleyLos Angeles Water Controversy (1981), which make the aqueduct project their primary focus.

However, as someincluding Catherine Mulhollandhave lamented, many of the water-issue books are dominated by political concerns and a seemingly unavoidable tendency to side with one group or another of the good guys du jour. I estimate that of the voluminous literature which exists concerning the history of Owens Valley and water in Southern California, Ms. Mulholland once stated, that about fifty percent is reliable while the remainder, based largely on secondary and often dubious sources, could be consigned to the fiction department.

Understandable, perhaps, for as the hard-bitten newspaper editor likes to observe, only trouble is interesting, and there is nothing like scandal to engage the attentions of an audience. Coupled with the temptation to judge the actions of those who lived a century ago through the lens of present-day political correctness, history often becomes subject to revision. It all became a bit too much for Ms. Mulholland, however, when she picked up an issue of the New York Times in 1991 to read an article citing Chinatown as a historical primer for understanding the practice of municipal predation upon water resources, resources to which, the Times writer maintained, the city had no right.

Galled that a crime melodrama, however artful, had come to be regarded by the uninformed as a kind of documentary work on the history of Los Angeles and dissatisfied by the paeans to Mulholland penned earlier in the century, she was moved to write William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles (2000), a biography of her grandfather that is a meticulous birth-to-death record of a remarkable life.

While that publication was both well received and thorough, in its original form it was nearly twice as lengthy, and in the editing process certain more personal gems were unfortunately lost. In that first manuscript, Ms. Mulholland traces at some length her own history and growing fascination with her subject, including recollections of the occasional encounters with those who simply had a friendly curiosity about my relationship to the engineer and who sometimes spoke of their admiration for your grandfather, who did so much for Los Angeles.

But in time, the burden of her familys name became increasingly apparent: As I grew older... certain darker brushes not only disturbedthey paralyzed me as I had no sure defenses against them. They could come unexpectedly, as on a night in the 1940s, when I sat listening to Art Tatums virtuoso keyboard improvisations at the Streets of Paris in Hollywood. During intermission, I fell into talk with the man next to me at the piano bar. Although in his cups, he was knowledgeable about the music and so when in the course of a genial exchange, he asked me my name, I was not prepared for his reaction.

Youre not related to that son of a bitch, are you? I tried to toss it off. Which son of a bitch did you have in mind? But I already knew what was coming, and it did: The one who stole the water.

There were other such encounters, including a moment when she took her place alongside a fellow student in an Old English Philology seminar at Cal-Berkeley, where she had relished the anonymity of being a Mulholland in a distant land. After the professor had called the roll, her classmate, who would eventually become known as the accomplished poet Jack Spicer, leaned over to whisper, Ive always wanted to meet one of