Aqueduct

Copyright 2016 Adele Perry

Third printing September 2018

ARP Books (Arbeiter Ring Publishing)

205-70 Arthur Street

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Treaty 1 Territory and Historic Mtis Nation Homeland

Canada R3B 1G7

arpbooks.org

Book design and layout by Mike Carroll.

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens on paper made from 100% recycled post-consumer waste.

Interior cover image: C.C. Chataway, Map of Winnipeg New Edition (Winnipeg: Western Map Company, 1919). Source: University of Manitoba Archives and Collections.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

This book is fully protected under the copyright laws of Canada and all other countries of the Copyright Union and is subject to royalty.

ARP Books acknowledges the generous support of the Manitoba Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Province of Manitoba through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Book Publisher Marketing Assistance Program of Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Tourism.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Perry, Adele, author

Aqueduct : colonialism, resources, and the histories we remember / Adele Perry.

(Semaphore series)

ISBN 978-1-894037-69-3 (paperback)

1. Municipal water supplyManitobaWinnipeg--History. 2. AqueductsManitobaWinnipegHistory. 3. Native peoplesColonizationCanada. I. Title. II. Series: Semaphore series

TD227.M35P47 2016 333.91009712743 C2016-900646-8

Contents

by Rick Harp

Note on the proceeds from aqueduct

The royalties from the sale of Aqueduct will be donated to Shoal Lake 40 First Nations Freedom Road fund. This fund sustains the Museum of Canadian Human Rights Violations located on the Shoal Lake 40 reserve, amongst other projects dedicated to the long road to reconciliation.

Foreword

RICK HARP

A t first blush, the story of the Greater Winnipeg Water District Aqueduct (also known as the Winnipeg Aqueduct) might seem of little consequence or interest to anyone except those curious about a particular time and place. But, like Adele Perry, I believe it actually represents a case study in colonialism, where the local and the global are one and the same. Across practically every dimension you can imagine, the story youre about to read epitomizes the immoral, inhumane, and, ultimately, imperial approach Canada has perpetrated against Indigenous peoples, their lands, and, of course, their waters for well over a century.

What may set this case of colonialism apartby degree, not in kindis the utter transparency of the injustice. Roughly a century ago, the emerging city of Winnipeg found itself in a serious predicament: it lacked a local water source to slake the thirst of its rapidly growing population. As you will soon learn, that quest led to the enactment of an ambitious and audacious plan to construct a truly massive aqueduct to permanently tap Shoal Lake so that Winnipeg residents roughly 150 kilometres away could enjoy an essential building block of public health: easy, reliable access to clean drinking water. But in so doing, city politicians and planners effectively cut off those Indigenous peoples who lived alongside and relied upon that very same lake for their survival and sustenance. For the First Nation we now know as Shoal Lake 40, the construction of the Winnipeg Aqueduct led to their isolation on an artificial island where, for nearly two decades, they have lacked access to clean drinking water.

Now, to say the municipal, provincial, and federal governments and bureaucracies of the day disregarded the rights of the peoples of Shoal Lake presumes the former had much, if any, regard for the concerns of the latter to begin with. As Perry well illustrates here in Aqueduct , Indigenous peoples interests or preferencesbasically, their very existencenever seriously registered on the radar of any level of government. More than once I was left shaking my head at the details of their arrogant actions. As for the intended beneficiaries, once that lake water flowed to the city, those who lived at its source would henceforth remain out of sight, out of mind.

It is doubtful one could find a more blatant example of settlers profiting off the resources of Indigenous peoples. To put it another way, the flipside of Winnipeggers prosperity has been the profound immiseration of the first peoples of Shoal Lake. Or even more bluntly, one sides loss constituted the others gain.

So what changed? How has this 100-year-old travesty shifted course to the point where a solution to Shoal Lake 40s water woes now seems to be at hand, and with the support of all levels of Canadian government? Honestly, that could be a book unto itself. This book is about what came before, a window into the elaborate and intricate system of colonial thought and action that infused the conception and creation of the Winnipeg Aqueduct, the kind of schema thats endured much longer than many Canadians would care to acknowledge.

As one of those born and bred Winnipeggers who came rather late to the story of how my city has gotten its water since 1919, I had no real appreciation of what quenching my thirst or taking my morning shower cost the people at the other end of the tap. That ignorance ended abruptly in June 2015, when my social media feed transmitted heart-breaking images of residents of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation left devastated by the news that the federal government of Stephen Harper had flatly refused to contribute its one-third share of the $30 million needed to construct Freedom Road, the road that would finally make a water treatment plant feasible for the community. A plant that would in turn bring to an end the shameful boil water advisory in place at Shoal Lake 40 since February 1997.

As one of over 78,000 Indigenous residents within the greater Winnipeg area, my outrage only intensified as I learned more about what it tookand what was takenfor me to enjoy convenient, reliable access to water. Thankfully, I wasnt the only one who felt this way. In response to a crowdfunding campaign I launched to raise Ottawas missing 10-million-dollar share and keep the spotlight on this deplorable situation, just over a thousand people (or the rough equivalent of one in 700 Winnipeggers) stepped up to pledge their support and more than $100,000. Weeks later, about the same number of residents took to the streets of downtown Winnipeg to march in support of the campaign to Honour the Source.

Actions like these helped set the stage for the tripartite announcement of December 17, 2015more or less 100 years to the day construction began on the Aqueductwhen the freshly minted federal government of Justin Trudeau joined together with the city of Winnipeg and province of Manitoba to declare their formal support of Freedom Road.

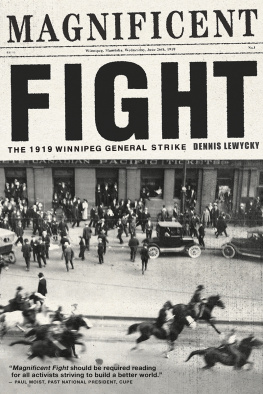

Aqueduct takes us through the seminal events and key drivers of those preceding 100 years. But instead of the hagiographical narratives of yesteryear propagated by civic boosters, Perrys account methodically exposes the removal of Indigenous resources to the exclusive benefit of a Canadian city for what it is: a massive project of empire legitimized via the logic and language of colonial erasure.

Theres been no end of mainstream historians who have written off Indigenous peoples (that is, when theyve written of them at all). It is a supreme testament then to the strength and determination of the people of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation that they have relentlessly fought such attempts at erasure, decade after decade. A more tenacious or savvy people you wont find anywhere.

Next page