WERE GOING TO RUN THIS CITY

Winnipegs Political Left after the General Strike

Stefan Epp-Koop

To my parents. For giving me a passion for learning and the desire to write.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Canada R3T 2M5

uofmpress.ca

Stefan Epp-Koop 2015

Printed in Canada

Text printed on chlorine-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper

19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the University of Manitoba Press, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca, or call 1-800-893-5777.

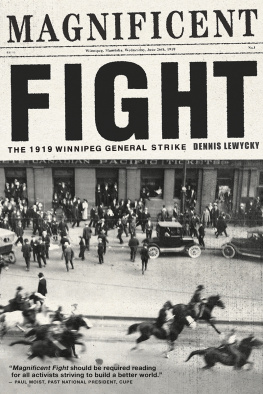

Cover photo: Winnipeg General Strike meeting at Victoria Park, 13 June 1919. Photo by L.B. Foote. Archives of Manitoba, N2747.

Cover design: TG Design

Interior design: Jess Koroscil

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Epp-Koop, Stefan, 1984, author

Were going to run this city : Winnipegs political left after the General Strike / Stefan Epp-Koop.

Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-88755-784-2 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-88755-475-9 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-88755-473-5 (epub)

1. Right and left (Political science)ManitobaWinnipeg History20th century. 2. General Strike, Winnipeg, Man., 1919. 3. Winnipeg (Man.)Politics and government20th century. I. Title. II. Title: We are going to run this city.

FC3396.4.E66 2015 971.274302 C2015-903496-5 C2015-903497-3

The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, Tourism, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

As a resident of Winnipegs West End, it is not hard to experience the legacy of the citys municipal politics of the 1930s. I occasionally walk past Jacob Penner Park, or down Agnes Street where the Independent Labour Party held rallies at a labour hall, or cross the Arlington Street Bridge into the North End, still home to many small Eastern European shops that are reminiscent of an earlier era. And, as I do, my mind once in a while drifts back to vivid newspaper descriptions or political circulars from eighty years ago; to imagine the school gymnasiums of my neighbourhood packed with people to hear John Queen or S.J. Farmer; to imagine a parade of thousands of workers coming down Main Street waving red banners and singing Soviet songs; or to walk down the elm-lined streets of Wolseley or River Heights and imagine dinner conversations denouncing the dangers of the Reds and radicals.

As an adopted Winnipegger, my exploration of this history occurred as I came to know and understand the city in its current form. There were moments, such as one walking to the City of Winnipeg Archives on a bitterly cold December day, where I wondered why I could not have been interested in something just a bit more exotic. But it was the localness of the work that excited me; the ability to connect actual places with the lived experience of people in Winnipeg and to begin to understand contemporary Winnipeg better through the lens of its history.

Even though nearly eighty years have passed since the municipal campaigns discussed in this book, there is more that remains the same in Winnipeg than a few landmarks and my imaginings. Many of the challenges and conflicts outlined in this book remain today, albeit in different forms. For example, while there may be less animosity between business and labour nearly one hundred years after the General Strike, the city remains deeply divided. Divisions of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status continue to shape the city and its politics. The North End, which plays a central role in this book, remains the home of people on the political margins. Now, however, the marginalized Ukrainian and Jewish populations that called the North End home in the 1920s and 1930s have been replaced by Aboriginal Canadians and newcomers from Asia and Africa. These new communities face many of the same challenges as their predecessors in the neighbourhood: racial discrimination, limited employment opportunities, and little political power, being a few.

Winnipeg remains a city where the political left has maintained a strong presence. Yet despite success in provincial and federal elections, the left has rarely succeeded in wresting control of municipal power from the Liberal and Conservative descendants of the business leaders who united to fight the General Strike in 1919. This informal alliance has been effective at controlling the municipal agenda in Winnipeg for most of the past eighty years. Similarly to the 1920s and 1930s, the left can count on roughly a third of seats in city council, a figure usually increased only in exceptional circumstances. This often means that these councillors essentially become the unofficial opposition rather than being central to the formation of municipal policy, a role that would have been familiar to Independent Labour Party (ILP) or Communist aldermen for most of the 1920s and 1930s.

Winnipegs mayoral races continue to be depicted as battles between the left and the right, and many parallels can be drawn between the campaigns of the 1920s and 1930s and those today. First, the city remains deeply divided between areas that support the candidates on the left and right. The electoral result in most neighbourhoods is easily predicted, with neighbourhoods won handily by one candidate or another. Second, the candidate on the left often faces accusations of being beholden to a political party, the New Democratic Party (NDP), while the candidate on the right is generally not perceived of as having party ties, even if they too are actively involved in a political party. This was regularly the case in the 1920s and 1930s, when accusations of partisanship were levelled against the ILP, but not against their business-oriented opponents, who in many ways acted as a party in all but name. And finally, there is often a great deal of fear generated about what might happen if the candidate on the left were to win. Just as in the 1920s and 1930s, the potential victory of a left-leaning candidate is cast as a harbinger of tax hikes and economic stagnation. This leads to movements to unite the right to prevent this from occurring, a phenomenon that has been a factor in Winnipegs municipal politics for the past eighty years.

While many of the issues that city council faced in the early years of the twentieth century have long since been settled, divisions continue over issues such as taxation, public transportation, the arguably disproportionate lack of municipal services in core neighbourhoods, and the role of government in addressing societal issues. In particular, a key issue in recent years has been the relationship between public and private services. This debate has been similar to the debates of earlier decades, with its focus on public control of services, workers rights, the long-term nature of contracts with private companies, and the profiting of these companies from municipal services. Even over a span of eighty years, the dividing lines in the city over these issues have remained essentially the same.