The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the General Endowment Fund of the Associates of the University of California Press.

William Mulholland

and the

Rise of Los Angeles

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2000 by the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mulholland, Catherine.

William Mulholland and the rise of

Los Angeles / Catherine Mulholland.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-520-21724-1 (alk. paper).

1. Water-supplyCaliforniaLos AngelesHistory. 2. Mulholland, William, 18551935. 3. EngineersCaliforniaLos Angeles

Biography. I. Title.

HD4464.L7 M85 2000

979.4'9404'092dc21 99-048289

[B] CIP

Manufactured in the United States of America

09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Chapter 24 contains material previously published in modified form as Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam, in The St. Francis Dam Disaster Revisited, edited by Doyce B. Nunis, Jr. (Los Angeles and Ventura: Historical Society of Southern California and Ventura County Museum of History and Art, 1995).

To the memory of Richard Perry Mulholland (19251992), the Chiefs only grandson

A story that was the subject of every variety of misrepresentation, not only by those who then lived but likewise in succeeding times: so true is it that all transactions of preeminent importance are wrapt in doubt and obscurity; while some hold for certain facts the most precarious hearsays, others turn facts into falsehood; and both are exaggerated by posterity.

Robert Graves, I, Claudius

Contents

Illustrations

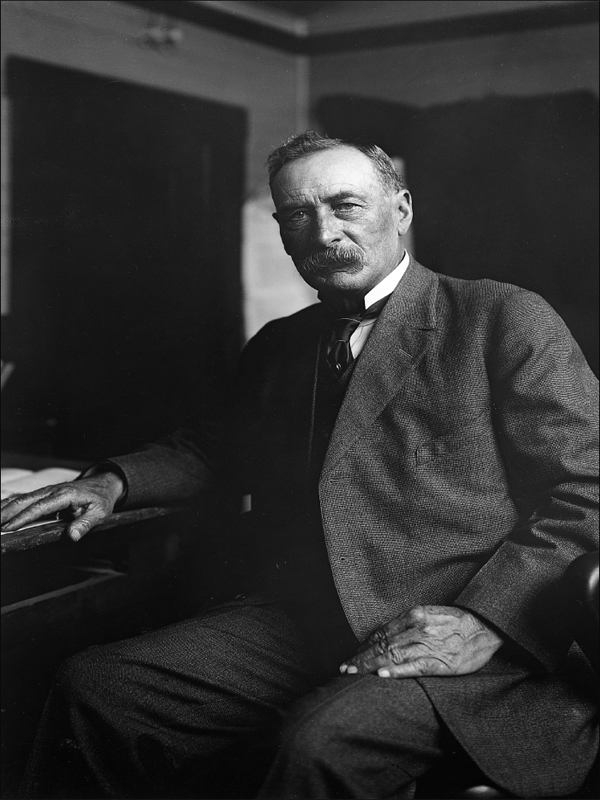

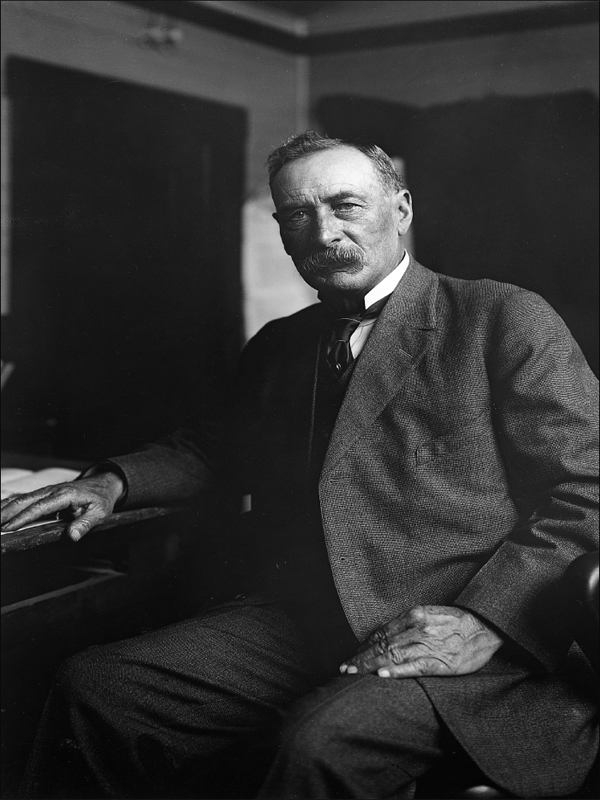

William Mulholland, 1916

plates follow page 136

MAPS

Preface

Los Angeles No ordinary rules explain its past growth or set limits to its future expansion. It has been, and will be, a law unto itself.

WILLIAM E. SMYTHE,

The Conquest of Arid America

A HISTORIC DISPUTE

William Mulholland presided over the creation of a water system that changed forever the course of Southern California history, and in so doing he became the focus of a controversy that has never died. When Los Angeles went water hunting and laid claim to the waters of the Owens River over two hundred miles away, its actions so conflicted with competing interests that they gave rise to a struggle of mythic proportions. Reading the varying accounts of this action reminds one of the classic paradox All Cretans are liars, said the man from Crete. Who lies? Does everyone lie or does everyone one tell the truth? Even if the dead could be brought back, could they tell us what we want to know? Writers who have scrutinized the same public documents, official records, and private correspondence have arrived at contrary conclusions, so the existing literature on the story of Los Angeless water is not only voluminous but also often dissonant.

When I began research for this work in 1989, four books on the subject especially deserved serious consideration, each offering different yet valuable versions of the water story. The important pioneer effort was The Water Seekers (1950), by Remi Nadeau, a highly readable work that subsequent scholarship has somewhat superseded. Water and Politics: A Study of Water Policies and Administration in the Development of Los Angeles (1953), by Vincent Ostrom, is probably the best and most precise single survey of the subject but tends to be impersonal in its treatment of the individuals involved in the story. Vision or Villainy: Origins of the Owens ValleyLos Angeles Water Controversy (1981), by Abraham Hoffman, is a fair-minded and thorough work, especially valuable for its examination of the roles J. B. Lippincott and the Reclamation Service played in the Owens Valley saga. The fourth, Water and Power (1982), by William Kahrl (editor of the estimable California Water Atlas), while containing a wealth of documentation, technical information, and a valuable bibliography, is also full of inaccuracies and, because of its unremittingly jaundiced view of Los Angeles and its water seekers, ultimately proves to be a polemic masquerading as a scholarly study. Water and Power has been influential, however, in subsequent works that have relied and elaborated on Kahrls views: Cadillac Desert (1986), a screed by Marc Reisner on the evils of water development in the West; Western Times and Water Wars (1992), by John Walton, a study of Owens Valley that is somewhat in the manner of the Annales school of French historiography as found in LeRoy Laduries Montaillou and that describes the purported injustice inflicted by large governmental power over a small region; and The Lost Frontier (1994), by John Sauder, an inquiry into the agricultural losses sustained in Owens Valley because of Los Angeless water development. Although none of the authors of this latter group is as extreme as the popular Western writer Wallace Stegner, who wrote that he considered building a dam evidence of original sin, each reflects the fin de sicle skepticism toward large water projects along with a disapproval of Los Angeles and a resolute bias favoring Owens Valley. The inclination to side with the underdog is powerful and humane but also risks committing what Bertrand Russell called the fallacy of the superior virtue of the oppressed. Even the objective scholar-historian Norris Hundley has described Los Angeles as the Wests most notorious water hustler in Water and the West (1975), and in his extensive overview of California water history, The Great Thirst (1992), he trivializes the building of the Owens Valley Aqueduct under a pejorative chapter heading, The Owens Valley Caper. These works contentions have helped create public perceptions such as a woman recently voiced at an environmental conference I attended when she fairly shouted, Mulholland was no engineer. All he did was take a few pipes up north and run water down and help make some men rich, or such as a recent news article expressed when it described the shadowy fiddling that sucked Owens Valley water into Los Angeles. In these versions, Mulholland emerges as an antihero rather than an admired bringer of water. As one of his nieces once ruefully remarked, The Greeks beat the Trojans, but now, after three thousand years, it is a greater compliment to be called a Trojan.

In fact, the whole thrust of the Los Angeles enterprise looked to the future. Just as Caesar did not look back to Alexander for his model of a Roman empire but anticipated as a model a kind of city-state existing in Romes own peripheries and provinces, so the leaders of an expanding Los Angeles looked to extend boundaries in order to create a new kind of city. What, after all, made this venture more reprehensible than those undertaken by other American cities that had gone distances to find water: New York to Croton, Boston to Lake Winnipesaukee, and San Francisco to the Tuolumne River in the Sierra Nevada mountain range? Who still rails against the New York Catskill project, which in its construction bought and drowned ten towns and villages, removed three thousand dead from thirty-two cemeteries, relocated eleven miles of rail track, and built ten highway bridges? Furthermore, the New York project was simply a water delivery system, while the Owens River project was to produce electrical energy as well, making it at the time not only a municipally owned utility but also one of the most valuable commercial enterprises in the United States.

Next page