CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

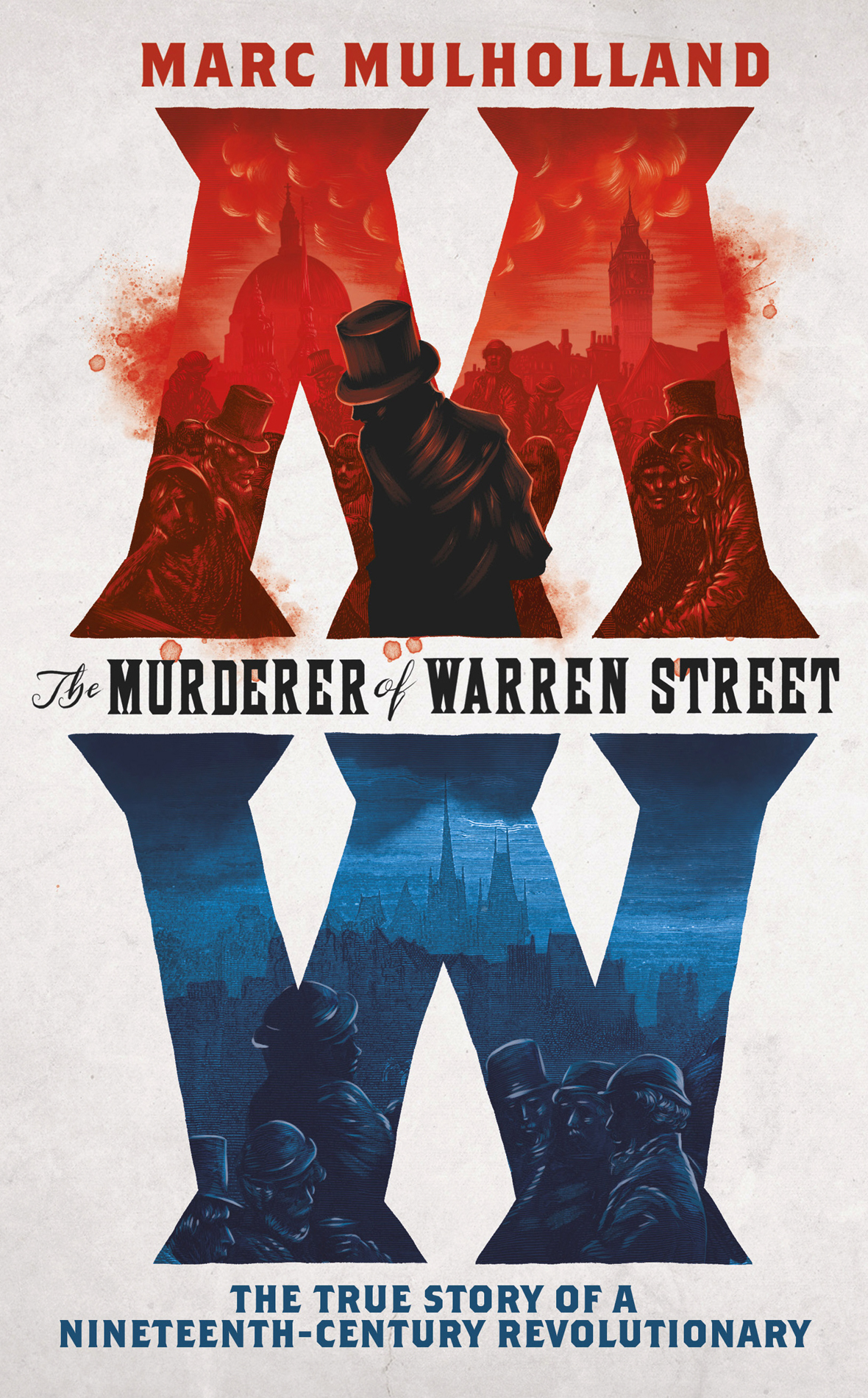

The true story of one of nineteenth-century Londons most notorious murderers.

On 8 December 1854, Emmanuel Barthlemy visited 73 Warren Street in the heart of radical London for the very last time. In just half an hour, two innocent men would be dead.

The newspapers of Victorian England were soon in a frenzy. Who was this foreigner come to British shores to slay two upstanding subjects? As Oxford historian, Marc Mulholland, has uncovered, Barthlemy was no ordinary criminal. Rather, here was a dedicated activist fighting for the cause of the oppressed worker, a fugitive shaped by the storms of revolution, counterrevolution and a society in the midst of huge transformation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marc Mulholland is a Professor of Modern History at St Catherines College, Oxford University. He specialises in the development of international socialism, the history of political thought, Revolution and modern Ireland. Marc is from County Antrim in Ireland, one of nine children. As his father was a forester he grew up in the woods at Portglenone. He lives in Oxford with his partner, Victoria.

To my mother, Ita, and in memory of my father, Dominic

Suddenly Barthlemy aimed a pistol and fired. Moore dropped dead as the maid ran screaming out of the front door. Brisbane Telegraph, 5 July 1854.

PREFACE

ONE CANNOT IMAGINE . Modern readers might be surprised at the differences between the two cities Wey described. Parisians would patiently queue, Londoners would rush and barge. Young Frenchwomen were repressed, their English counterparts flirtatious.

Francis Wey knew Paris and London because he wandered their streets. His pavement-level flneur view of society had become fashionable by the 1840s. The flneur is the casual wanderer who saunters about, led by no plan other than their own restless curiosity, observing what is happening in streets and alleyways. He sees what most people fail to see because they are rushing by, intent on business.

For Charles Baudelaire, the nineteenth-century poet and essayist, the flneur was the detached observer, the botanist of the sidewalk. Baudelaire advises us to take a seat at the pavement caf and to watch passers-by. When one particular unknown face piques our interest perhaps he looks troubled or distracted, or she is a beauty in rags, or his eyes blaze with a criminal intent we rise and hurl ourselves headlong into the midst of the throng in pursuit of the unknown, half-glimpsed countenance. We leave the familiar routes of respectable workaday life for the mysterious, overlooked, crowded passageways and haunts of the underworld. Baudelaire certainly appealed to artists and bohemians. As a rule, however, historical writers a sober lot prefer to know where they are going. The great English historian of the nineteenth century, Lord Acton, advised scholars to choose a problem before beginning their historical researches. This is good advice. But it is also possible to write history as a flneur. Rather than focusing on a problem, we might choose one character from history neither a great man nor a great woman and decide to follow them. What might we then see that otherwise would remain overlooked?

In this book the reader will track the unknown, half-glimpsed Emmanuel Barthlemy: nineteenth-century revolutionary, conspirator, gaol-breaker, duellist, inventor and murderer. In pursuing Barthlemy we not only uncover an extraordinary life, but travel the world through which he moved. This was a world that crossed national borders and its richness is best appreciated from multiple angles. We learn how Barthlemy saw society and how society saw him. As we make our way, we look about ourselves and see a world in transformation, in the midst of revolution and counter-revolution, becoming modern. Much of what we see is surprising and unfamiliar. But we find also much that is strikingly relevant to our own times.

In 1827 an Irish actress, Harriet Smithson in January 1861, he began in a completely different register, with a meditation on the June Days, a doomed workers rebellion, and its enigmatic leader, Emmanuel Barthlemy. Revolutionary romanticism had come to life. This is a book about that life and the world it reveals.

THE MAN I NOW SEE IS THE MAN WHO SHOT ME

WHEN EMMANUEL BARTHLEMY visited George Moore for the last time, he was not in a good mood. Perhaps few of us would be: it was a dank, freezing cold, wet night. Barthlemy was footsore and weary, and he had plenty on his mind. In his pocket a ticket for travel to the Continent: his plan, to assassinate the Emperor of the French.

Tying up loose ends in London was proving to be a complex business and Barthlemy had decided to work off his frustration by practising his pistol-shooting at the Gun Tavern at Westminster, near Buckingham Palace. But on his way he met with a mysterious woman and between them they concocted a plan to visit George Moore, Barthlemys former employer.

When they arrived at Warren Street it was just gone eight in the evening. The overture was playing at Her Majestys Theatre in the Haymarket and the elegant audience there, glorious with beauties and with riches, was settling in for the evenings opera performance. At the same time, in the teeming slum streets, workers emerging from a days labour were crowding round shabby stalls and shops. Under the three golden balls identifying the pawnbrokers establishment they presented their scanty possessions and in return the capitalist lent them housekeeping money. This is how the rich lived and the poor survived. It was the bustling, energetic, often desperate face of London.

The date was 8 December 1854. England, in alliance with France, had been at war with Russia since March. Florence Nightingale was nursing the diseased British expeditionary force at Scutari on the Crimean peninsula. British public opinion had scorned Napoleon III, ruler of France, as a despotic upstart. But now they celebrated him as a stout and faithful ally. Crude portraits of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte and his Empress, Eugnie, were on display all over London. For a revolutionary like Barthlemy, vehemently opposed to the Bonapartist dictatorship, this vexed him almost to wildness. Never had he felt more of a foreigner in England.

Only a few years earlier, in 1848, revolution had swept the Continent, and Barthlemys dreams had appeared to be on the brink of fulfilment. But now reaction was inexorably rolling back the radical wave. Cities across Europe had risen in revolt against their monarchs in 1848, only to be suppressed by armies based on peasant recruitment. Now, in its aftermath, the religious, the conservative, and the revolutionary contended for the ear of the people. As a revolutionary, Barthlemy knew that the influence of his party was diminishing.

Barthlemy stopped at 73 Warren Street, a large townhouse and workplace near the juncture with Tottenham Court Road. He was in Fitzrovia, close to the centre of radical London. Barthlemy knew the area well.

Barthlemy was a familiar figure in Londons radical community, both natives and exiles from European countries. But he was little known outside its ranks. For London was not just a centre of political agitation or a bolthole for revolutionaries. It was, primarily, the beating heart of the most extraordinary economic transformation to date. Only three years earlier the Great Exhibition had showcased Britains world-beating industrial might. Londons docks were crowded with commercial shipping and fragranced by cotton, preserved fruits, spices, dyes, spirits, perfumes and drugs, all piled high in warehouses or, if unsold, burnt in a huge furnace known as the Queens Pipe. The railways had tied together the country. In 1829 the first railway passenger service opened between Liverpool and Manchester. By the middle of the century railways criss-crossed the United Kingdom. For