ALEXANDER BELL is Head of Policy to the Government of Scotland and responsible for the worlds first national integrated water policy. Previously he has worked as a journalist for the BBC and The Observer .

Follow him on Twitter at @mrpeakwater .

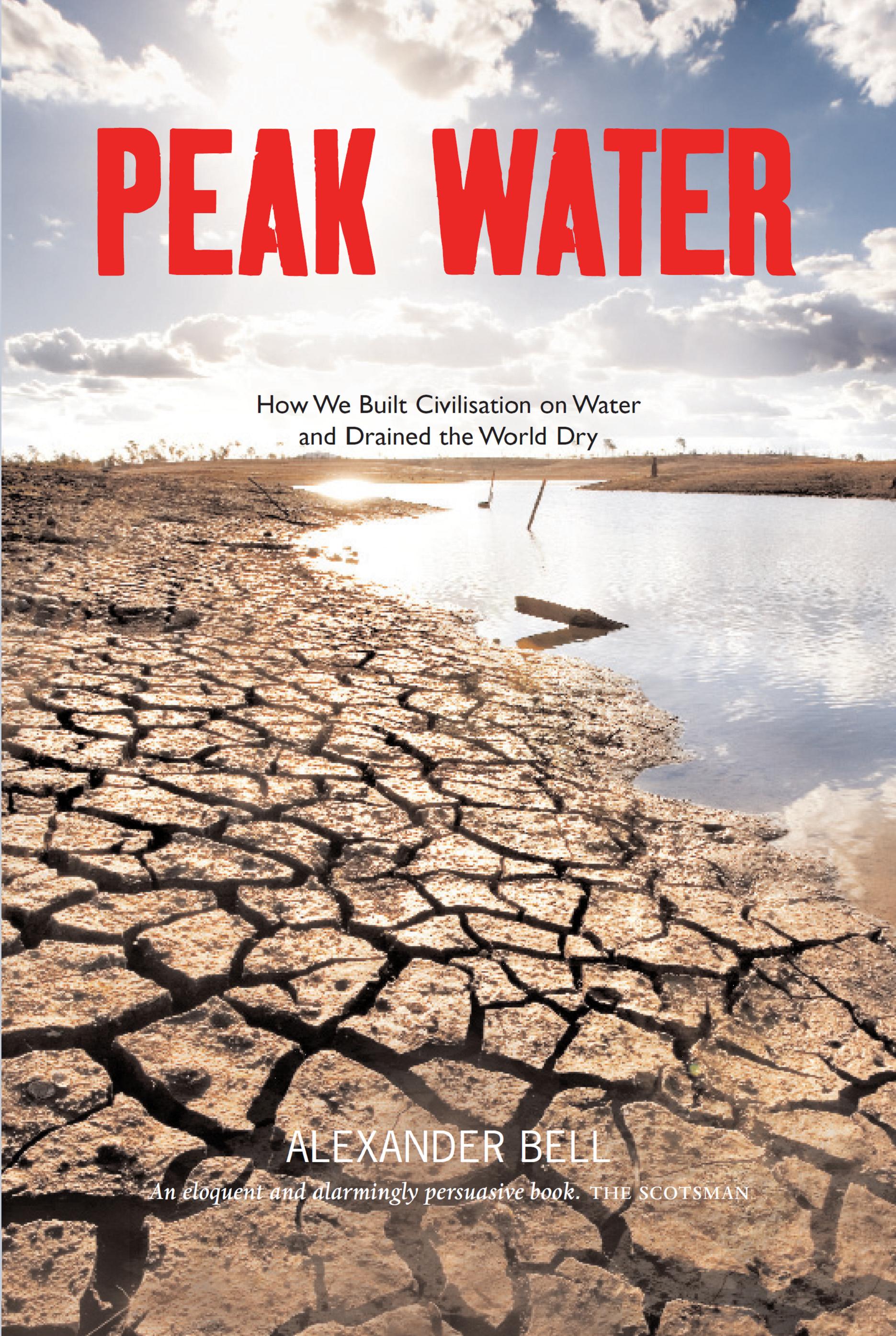

Peak Water

How We Built Civilisation on Water and Drained the World Dry

ALEXANDER BELL

Luath Press Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2009

New edition 2012

eBook 2012

ISBN (Print): 978-1-906817-71-8

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-21-2

The authors right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Alexander Bell 2009

Table of Contents

Introduction

CHILDREN ARE PLAYING on the beach ahead, digging castles in the sand and cutting channels of water. At the caf, I look out to the sea slipping into the horizon. The day is warm enough, a mix of sun, wind and occasional rain typical of a Scottish spring. I feel good in the beautiful city of Edinburgh, on the beach, breakfast on the table and happy people enjoying the break of winter. This is civilisation at its easiest.

The children are doing what we all did as youngsters playing with water. We have all stood on the beach and marvelled, both at the scale of the sea and the patterns of the streams that flow across the sand. The water dwarves us, putting us in our place in the scheme of the universe, while also tempting us in, to divert its currents and immerse ourselves in the waves.

On the table is a glass of orange juice, a coffee and a bacon sandwich, along with my laptop. If this is all sounding a little too life-style perfect, forgive me there is a point. Between the beach and the breakfast table is most of what you need to know about the water crisis. There is a plenty of water in the world we are a ball of blue in the infinite expanse of dark space but 97 per cent of it is seawater. Of the remaining three per cent, much of which is inaccessible in ice caps and remote locations, we are making ever greater demands.

The chair I sit on required water to be made. Roughly 20 per cent of the water we use is consumed by industry, making things like furniture, clothes and the laptop computer. Stuff is quite thirsty but not as thirsty as agriculture, which consumes around 70 per cent of all the freshwater mankind uses. The orange in the glass, the wheat for the bread, the milk for the coffee all require large amounts of water to be grown, while the bacon and all meat production needs huge amounts of water. Life in the developed world lots of stuff and a steady supply of food means we need lots of water. Civilisation, and by that I mean the process of change that has taken us from the camp fire to the city, is thirsty.

The crisis we are facing is because there are lots more people on the planet who want to have more stuff and to eat better food but who do not live near water supplies. If you live in Scotland and are happy to eat locally grown food and stuff that is manufactured in your neighbourhood, then there is no problem. You have lots of water for all your needs. If you live in large stretches of western USA, Mexico, the Middle East, parts of China or around the Mediterranean then you are quite likely living beyond your water means and that causes the crisis.

The problem is that the water is not where the people are Canada is soaking, but is home to only 35 million people. India has around one billion people and is running short. Beijing, capital of the worlds boom nation China, is sinking into the ground because so much water has been pumped up from the land it sits on. The world is currently looking to Africa for its food but the water table in much of eastern sub-Saharan Africa is dropping as the developed world drinks parts of the continent dry.

The United Nations thinks that the global population will rise from around 6.5 billion today to around nine billion in 2050. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN (FAO) estimate that to feed the extra people, we will need to increase food production by 70 per cent. To do that will require twice the amount of water used in agriculture than at present. However, scientists such as those in the Boundary Group believe we are already taking around two thirds of the available water. And that is our problem more people may well need more accessible water than exists. Civilisation could run dry.

This book explains that ordered life began at the point when mankind began to get the water to follow his wishes. The irrigation ditch is the true cradle of civilisation. The more civilised we became, the more water we needed. The connection between the two between water control and civilisation, was obvious to a Mesopotamian or a Roman, who celebrated their mastery of H O in fountains and gardens. Modernity does a good job of hiding our vital dependence on water the pipes are tucked away out of sight. Peakwater attempts to make them visible again.

The idea of water wars is a popular idea suggesting we may yet fight for the blue stuff much as wars have been fought for land and oil. There will be battles for rivers and wells, but the real battle will not be with guns. It is a battle for the future of civilisation a battle for the way mankind lives on the planet. Our existing system depends on water following our whims. Peakwater asks what civilisation will look like when we are the ones who have to follow the water again.

This book is a flow across history to reveal a hidden story of our most important resource a tale for the general reader about the essence of life.

It is dedicated to Murdo and Eilidh, the beginning of promise, and to Mo, my love.

I THE FIRST TASTE

WATER IS A RENEWABLE RESOURCE, yet it is running out. How do we explain that puzzle? The answer lies in the way mankind has developed over the last 6,000 years. We invented and expanded civilisation, which has given us many wonderful things and allowed the population to dramatically increase. When lots of people want to enjoy a civilised lifestyle, they drain water reserves. By repeating habits begun millennia ago, we empty the wells that have made our cities and nations great. To understand this, we need to float down the river of history and watch as man learns to tap the essence of all life.

Chapter One Wheres the Water?

LEONARDO DA VINCI would have marveled at the news channels in 2012. In the spring of that year England was suffering from a drought. TV screens were busy with experts talking of a crisis as taps were turned off and farmers worried for their crops. By the summer, England experienced some of the highest rain fall on record which resulted in floods across the country. There is something particularly telegenic about water, and the TV news ran a torrent of footage showing fields covered in water and desperate home-owners mopping up sodden possessions.

There seems something inconsistent here. Leonardo da Vinci thought the same thing 500 years ago. One of the many areas the renaissance genius studied was water. The river Arno, which runs through Florence, fascinated him. He wondered where the water came from to keep the current flowing. His notes on this laid the foundations for some modern water studies. Leonardo was worried about the biblical flood. He couldnt square the sudden appearance, and disappearance, of a vast amount of water, as described in scripture, with what he knew about the real substance. Where did it all go? How did it flow away, if there was no current? Yet the idea of a deluge fascinated him. He drew images of what it might look like, capturing the sense of chaotic power that a huge body of water has. As such, Leonardo identified a vital quality of water. It can be measured, and follows predictable patterns, but it is also wild.

![David E Newton] - The global water crisis : a reference handbook](/uploads/posts/book/104432/thumbs/david-e-newton-the-global-water-crisis-a.jpg)