Progress

Its all over our televisions, newspapers and the internet. Every day were bludgeoned by news of how bad everything is Brexit, financial collapse, unemployment, poverty, environmental disasters, disease, hunger, war. Indeed, our world now seems to be on the brink of collapse, and yet:

Weve made more progress over the last 100 years than in the first 100,000

285,000 more people have gained access to safe water every day for the last 25 years

In the last 50 years world poverty has fallen more than it did in the preceding 500

Contrary to what most of us believe, our progress over the past few decades has been unprecedented. By almost any index you care to identify, things are markedly better now than they have ever been for almost everyone alive.

A Oneworld Book

Published by Oneworld Publications 2016

This ebook published by Oneworld Publications 2016

Copyright Johan Norberg 2016

The moral right of Johan Norberg to be identified as the Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-950-1

ISBN 978-1-78074-951-8 (ebook)

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

UK

To Alicia, Alexander and Nils-Erik its your world now.

[T]he Progress of human Knowledge will be rapid, and Discoveries made of which we have at present no Conception. I begin to be almost sorry I was born so soon, since I cannot have the Happiness of knowing what will be known 100 Years hence.

Benjamin Franklin, 1783

Contents

Introduction

The good old days are now

Nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory.

Franklin Pierce Adams

Terrorism. ISIS. War in Syria and Ukraine. Crime, murder, mass shootings. Famines, floods, pandemics. Global warming. Stagnation, poverty, refugees.

Doom and gloom, everywhere, as a woman on the street responded when public radio asked her to describe the state of the world.

This is what we see in the news, and it seems to be the story of our time. An article about the zeitgeist ahead of New Years Eve 2015 in the Financial Times ran with the headline: Battered, bruised and jumpy the whole world is on edge.

These perceptions feed the fear and nostalgia on which Donald Trump has built his US presidential campaign. Fifty-eight per cent of those who voted for Britain to leave the EU in the countrys recent referendum say life is worse today than thirty years ago. In 1955, thirteen per cent of the Swedish public thought that there were intolerable conditions in society. After half a century of expanded human liberties, rising incomes, reduction in poverty and improved health care, more than half of all Swedes thought so.

Many experts and authorities agree. General Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, recently testified before US Congress: I will personally attest to the fact that... [the world] is more dangerous than it has ever been.

On the political left, activist Naomi Klein argues our civilization is on a collision course, and that we are destabilising our planets life support system.

I used to share their pessimism. When I began to shape my worldview in Sweden in the 1980s, I found modern civilization hard to stomach. Factories, highways and supermarkets to me were a dismal sight, and modern working life seemed sheer drudgery. I associated this new global consumer culture with the problems of poverty and conflict that television brought into our living room. Instead, I dreamed of a society that put the clock back, a society that lived in harmony with nature. I hadnt thought about the way people had actually lived before the Industrial Revolution, without medicines and antibiotics, safe water, sufficient food, electricity or sanitary systems. Instead I had thought of it more in terms of a modern excursion into the countryside.

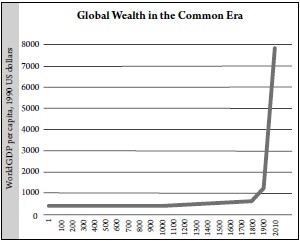

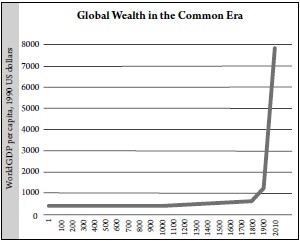

Source: Maddison 2003.

As part of my studies, I started reading history and travelling the world. I found I could no longer romanticize the good old days once I began to understand what they had really been like. One of the countries on which I focused my studies experienced chronic undernourishment it was poorer, with shorter life expectancy and higher child mortality than the average sub-Saharan African country. That country was my ancestors Sweden, 150 years ago. The truth is that, if we care to turn the clock back, the good old days were awful.

Despite what we hear on the news and from many authorities, the great story of our era is that we are witnessing the greatest improvement in global living standards ever to take place. Poverty, malnutrition, illiteracy, child labour and infant mortality are falling faster than at any other time in human history. Life expectancy at birth has increased more than twice as much in the last century as it did in the previous 200,000 years. The risk that any individual will be exposed to war, die in a natural disaster, or be subjected to dictatorship has become smaller than in any other epoch. A child born today is more likely to reach retirement age than his forebears were to live to their fifth birthday.

War, crime, disasters and poverty are painfully real, and during the last decade global media has made us aware of them in a new way live on screen, every day, around the clock but despite this ubiquity, these are problems that have always existed, partially hidden from view. The real difference now is that they are rapidly declining. What we see now are the exceptions, where once they would have been the rule.

This progress started with the intellectual Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when we began to examine the world with the tools of empiricism, rather than being content with authorities, traditions and superstition. Its political corollary, classical liberalism, began to liberate people from the shackles of heredity, authoritarianism and serfdom. Following hot on its heels was the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century, when the industrial power at our disposal multiplied, and we began to conquer poverty and hunger. These successive revolutions were enough to liberate a large part of humanity from the harsh living conditions it had always lived under. With late twentieth-century globalization, as these technologies and freedoms began to spread to the rest of the world, this was repeated on a larger scale and at a faster pace than ever before.

Humans are not always rational or benevolent, but in general they want to improve their lives and the lives of their families, and with a tolerable degree of freedom they will work hard to make this happen. Step by step, this adds to humanitys store of knowledge and wealth. In this era, more people are allowed to experiment with different perspectives and solutions to problems than before. So we constantly accumulate more scientific and other knowledge and every individual can contribute and achieve on the shoulders of hundreds of millions who have come before in a virtuous cycle.

This book is about humanitys triumphs. But it is not a message of complacency. It is written partly as a warning. It would be a terrible mistake to take this progress for granted. We have lived with these problems for most of history. There are forces at work in the world that would destroy the pillars of this development the individual freedoms, open economy and technological progress. Terrorists and dictators do what they can to undermine open societies, but there are also threats from within our societies. There is widespread resentment against globalization and the modern economy from populists on both the left and the right. We can see the familiar hostility to the cosmopolitan, urban and fluid society that there has always been from those who are socially conservative, but today it is combined with the sense that the world outside is dangerous, and that we must build literal and figurative walls.

Next page