Contents

Published by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39-41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.introducingbooks.com

ISBN: 978-184831-778-9

Text copyright 2011 David Orrell

Illustrations copyright 2012 Icon Books Ltd

The author has asserted his moral rights.

Edited by Duncan Heath

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Further Reading

Roger E. Backhouse, The Penguin History of Economics, Penguin (2002)

Eric D. Beinhocker, Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics, Harvard Business School Press (2006)

Todd Buchholz, New Ideas from Dead Economists: An Introduction to Modern Economic Thought, Penguin, revd edn (1999)

Herman E. Daly, Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development, Beacon Press (1996)

Robert L. Heilbroner, The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times, and Ideas of the Great Economic Thinkers, Penguin, 7th revd edn (2000)

Benot B. Mandelbrot and Richard L. Hudson, The (Mis)Behaviour of Markets: A Fractal View of Financial Turbulence, Basic Books (2004)

David Orrell, Economyths: Ten Ways That Economics Gets it Wrong, Icon Books (2010)

Steven Pressman, Fifty Major Economists, Routledge, 2nd edn (2006)

What is economics?

Economics is the study of how goods and services are produced, distributed, and consumed by society. Because resources are usually assumed to be in short supply, the field was described by English economist Lionel Robbins in 1935 as the science of scarcity.

The word economics was coined from the Greek words oikos (household) and nomos (law), so it means something like household rule or home management.

Though household is now generalized to include individuals, companies, countries, and the entire world system.

While people have been calling themselves professional economists only since the 19th century, the field has roots that go back much further.

Old money

Economic thought is at least as old as money itself.

The earliest coins were made from precious metals such as gold and silver. They are believed to have first appeared around the 6th century BC in what is now Turkey, but were soon in use around the civilized world, from Mesopotamia to Persia to India to China.

Ancient versions of economic ideas therefore existed in many different countries.

However, because economics has long modelled itself after sciences like physics, it has been shaped most of all by the Western scientific tradition, which itself is rooted in the ideas of Greek philosophers.

Pythagoras

The philosopher Pythagoras (c. 570c. 495 BC) is today associated mostly with mathematics, and his famous theorem about right-angled triangles that we all learn at school. But he has had a lasting influence on science in general, including economics.

Pythagoras was considered a demi-god by the Greeks. His birth was predicted by the oracle at Delphi, and it was rumoured that his father was the god Apollo.

As a young man, I travelled the world, learning from mystics and philosophers.

On my return, I set up school in a cave, teaching mathematics.

His school grew into what amounts to a pseudo-religious cult, based on the worship of number. The Pythagoreans were highly secretive and left no written documents, so we only know about them indirectly.

Harmony of the Spheres

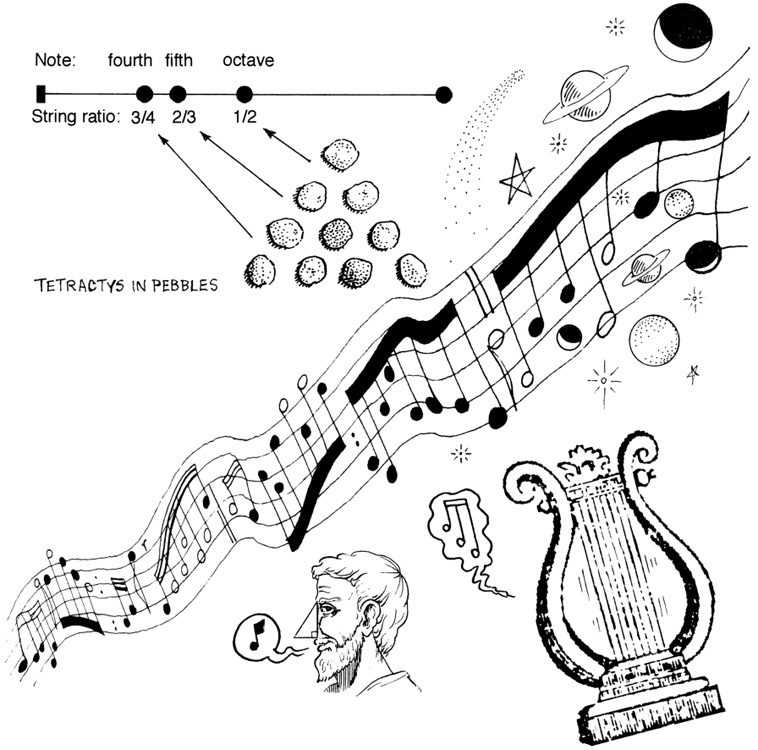

The Pythagoreans believed that all things were composed of number. Each number had a special, almost magical significance. The most sacred number was 10, which was symbolized by the tetractys.

Pythagoras is credited with the discovery that musical harmony is based on numerical ratios between string lengths. Because music was considered to be the most mysterious of art forms, this backed up the belief that the entire cosmos was based on number: what the Pythagoreans called the Harmony of the Spheres.

Economics, and money itself, are also based on the Pythagorean idea that all things can be reduced to number. Indeed, it is believed that Pythagoras was involved in introducing the first coinage to his region.

Oikonomikos

The word economics was derived from a work by the philosopher Xenophon (431c. 360 BC), who was influenced by Pythagoras. His tract Oikonomikos described how to efficiently organize and run an agricultural estate.

It must, I should think, be the business of the good estate manager at any rate to manage his own house or estate well.

He argued that complicated tasks could best be carried out through division of labour. An advantage of cities such as Athens, which was growing rapidly in size and complexity, was the availability of a variety of specialists. In smaller towns, people had to carry out more tasks themselves, which was less efficient.

While this conclusion predated Adam Smiths thoughts on the same topic by a couple of millennia (see ), in a slave-based society the coordinating of these specialists was a task for the estate manager, not the markets.

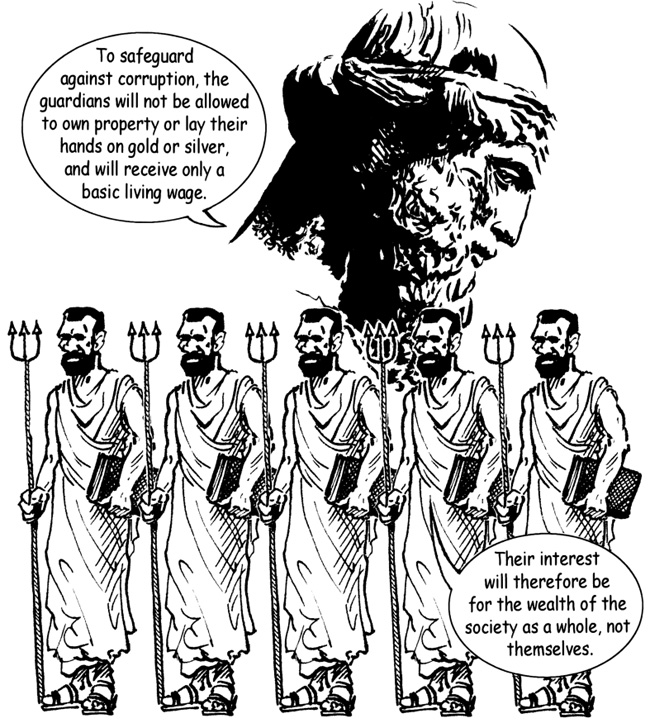

Platos Republic

Plato (427347 BC) took the idea of an optimally-managed estate a step further with his Republic, which described a utopian society ruled over by philosopher kings known as guardians.

To safeguard against corruption, the guardians will not be allowed to own property or lay their hands on gold or silver, and will receive only a basic living wage.

![David Orrell [David Orrell] - Quantum Economics](/uploads/posts/book/114631/thumbs/david-orrell-david-orrell-quantum-economics.jpg)