Table of Contents

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

FOREWORD

Norman E. Borlaug

Jimmy Carter

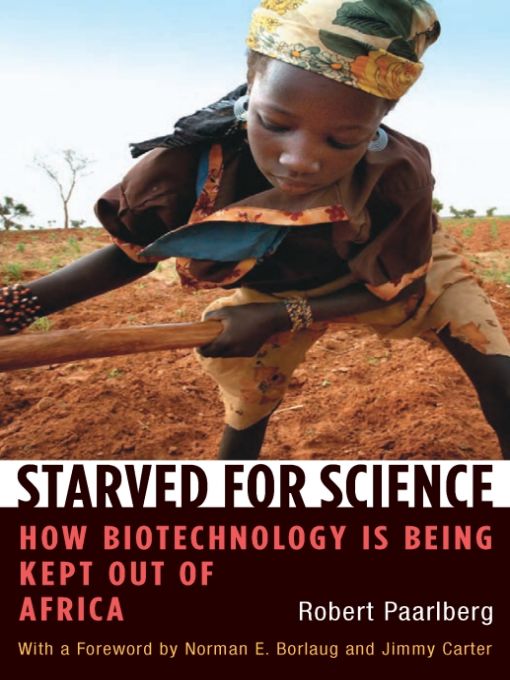

Robert Paarlberg is a leading scholar on the role of science and technology in smallholder agricultural development in Africa, and in particular, how governments and civil society have responded to such innovations. In this book he shows how a recent withdrawal of donor support for modern agricultural science in Africa, plus outright opposition to new farm science on the part of some global pressure groups, is contributing directly to the continued growth of poverty and hunger in rural Africa.

We share with him his concern about the lack of support for science and technology in Africa. According to the 2008 World Development Report, which this year features agriculture, Africa has only increased its agricultural research investment by 20 percent over the past twenty years, compared to a threefold increase in Asia. Whereas science has been used to boost farm productivity in Asia, raising rural income at the same time, smallholder farmers in Africa have remained starved for science. Less than one-third of Africas cropland is planted to improved seed varieties, compared to 82 percent of cropland in Asia, and average cereal yields in Africa are less than one-third as high as in Asia.

In the early 1990s, Paarlberg was among the first to sound the alarm about the deadlock between agriculturalists and environmentalists over what constitutes sustainable agriculture in the Third World. This debate has confusedif not paralyzedmany in the international donor community who, afraid of antagonizing powerful environmental lobbying groups, have turned away from supporting science-based agricultural modernization projects still needed in much of smallholder Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America. This confusion and paralysis is now most obvious in the case of agricultural biotechnology. The science of genetic engineering has significant potential to help rural Africa, particularly since it can now speed the development of crop varieties better able to tolerate stress factors such as drought. Yet the governments and nongovernmental advocacy groups of most prosperous countries, particularly in Europe, are resisting the introduction of modern agricultural biotechnology into Africa.

In 2000 a joint U.S.-European Union Biotechnology Consultative Forum was appointed by the presidents of the United States and the European Union to look at the full range of issues that have polarized thinking about biotechnology, especially in food and agriculture, on each side of the Atlantic. Although significant differences of opinion existedmainly related to the regulatory structure involved with certifying agri-biotech productsmost of the twenty U.S. and European experts on the panel agreed that agricultural biotechnology holds great promise for dramatic and useful advances in the twenty-first century. In effect, it confirmed the views of the most prestigious national academies of science in North America and Europe (including the Vatican), none of which found any new risks to human health or the environment from any of the applications of crop biotechnology commercialized so far, and all of whom confirm the potential of genetic engineering to improve the quantity, quality, and availability of food supplies.

Even so, the debate about the safety and utility of genetically modified (GM) crops continues to grow, enough to discourage governments in Africa from approving the technology for commercial use. This is a rich-world argument that is hurting the poor. Although there have always been those in society who resist change, the intensity of the attacks against GM crops from some quarters is unprecedented, and in certain cases, even surprising, given the potential environmental benefits that such technology can bring by reducing the use of pesticides.

In the past five years, the presidents of several African countries facing widespread drought, crop failure, and hunger have even banned the distribution of donated maize from the United States as food aid, having been told by antibiotechnology groups that this food was poison because it contained genetically modified kernels. Based on such misinformation, they have been willing to risk thousands of additional starvation deaths rather than distribute the same maize that regulators approve in the United States and that Americans have been eating for more than a decade with no documented ill effect.

Paarlberg shows that low-income, food-deficit nations are being advised by governments and pressure groups in privileged nations to reject agricultural biotechnology mostly because this is a technology the rich countries themselves do not happen to need. When it comes to new applications of medical science, which prosperous countries still need and value, genetic engineering is not seen as a threat, and is not regulated to death. Only in the area of agriculture, where new science is no longer needed by the richbecause their citizens are well fed and their farmers already highly productiveare stifling regulations imposed.

These inconsistent views regarding the use of transgenic crop technology in Europe and elsewhere might have been avoided had more people received a better education in biological science. This educational gap, which has resulted in a growing and worrisome ignorance about challenges and complexities of agricultural systems, needs to be addressed without delay.

Privileged societies have the luxury of adopting a very low-risk position on the GM crops issue, even if this action later turns out to be unnecessary. But the vast majority of humankind does not have such a luxury, and certainly not the hungry victims of wars, natural disasters, and economic crises.

The policy debate about the suitability of biotech agricultural products should focus less on risksince after more than a decade of commercial experience with the technology, no new risks have yet been documentedand more on access for the poor. Access to biotech seeds by poor farmers is a dilemma that will require interventions by governments and the private sector. Seed companies can help improve access by offering preferential pricing for small quantities of biotech seeds to smallholder farmers. Beyond that, public-private partnerships are needed to share research and development costs for pro-poor biotechnology. Of course, there is nothing magic in an improved variety alone. Unless that variety is nourished with fertilizerschemical or organic, ideally both in combinationand grown with good crop management, it will not achieve much of its genetic yield potential.

African governments, following the lead of Europe, have so far resisted the use of modern crop biotechnology. Africa has already missed the industrial revolution and the tractor and fertilizer revolution. As things stand today, Paarlberg shows, there is a risk it will miss the biotechnology revolution as well. This would be tragic, since Africa, with the largest proportion of its population engaged in agriculture, has the most to gain from biotechnologies that protect crops from disease and insects, increase yield stability under drought, enhance nutritional quality, and lower production costs.

Next page