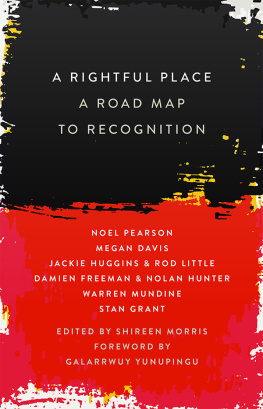

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

This collection copyright Black Inc. & Shireen Morris 2017.

Copyright in the foreword and individual essays is retained by the authors, who assert their rights to be known as the author of their work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

A rightful place: a road map to recognition/Shireen Morris, editor; Noel Pearson, Stan Grant, Galarrwuy Yunupingu, Damien Freeman, Rod Little, Jackie Huggins, Megan Davis, Nolan Hunter, Warren Mundine, contributors.

9781863959131 (paperback)

9781925435504 (ebook)

Aboriginal AustraliansLegal status, laws, etc. Torres Strait IslandersLegal status, laws, etc. Law reformAustralia. Civil rightsAustralia. Equality before the lawAustralia. AustraliaPolitics and government.

Morris, Shireen, editor. Pearson, Noel, 1965. Grant, Stan, 1963. Yunupingu, Galarrwuy, 1948. Freeman, Damien. Little, Rod. Huggins, Jackie, 1956. Davis, Megan, 1975. Hunter, Nolan. Mundine, Warren.

Cover design by Peter Long

Text design and typesetting by Tristan Main

Foreword

G ALARRWUY Y UNUPINGU

T he writers in this book are all serious people, and the knowledge they share with us is valuable. They are sharing with us their learning, experience and expertise at a time of great importance to the Australian nation: when the people will decide whether or not they will deal with the relationship between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the settlers who came after 1788. As I see it, the nation is at an important crossroads either a real process of settlement will now take shape, or the nation will turn its back on these issues.

I recommend that we look to the Yolngu principles of makarrata, which are basic principles that apply at many levels. The essays in this book play an important part in this process. They give us the views and ideas that we must consider and which shall inform us as we go forward.

The starting point for makarrata is a position from an aggrieved party. The aggrieved party here is the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. I cannot set out here all of the ways in which we have been wronged but they are many, and these are terrible acts that have been committed against my people. Now, in the spirit of makarrata, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait leadership at Uluru has given voice to our grievances in the Uluru Statement. The Uluru Statement has set out the issues for assessment. It takes us into a process where we can now get serious and look to a proper settlement.

The principles of makarrata that guide us remain the same as they were for thousands of years.

First, the disputing parties must come together. Then each party, led by their elders, must speak carefully and calmly about the dispute. They must put the facts on the table and air their grievances. If a person speaks wildly or out of turn he or she is sent away and shall not be included any further in the process. Those who come for vengeance, or for other purposes, will also be sent away for they can only disrupt the process.

The leaders must then seek a full understanding of the dispute: what lies behind it, who is responsible, what each party wants, and all things that are normal in peacemaking efforts. When that understanding is arrived at, then a settlement can be agreed upon. This settlement is also a symbolic reckoning an action that says to the world that from now on and forever the dispute is settled; that the dispute no longer exists; it is finished. And from the honesty of the process and the submission of both parties to finding the truth, the dispute is ended. In past times a man came forward and accepted a punishment, and this man once punished was then immediately taken into the heart of the aggrieved clan. His wounds were healed by the women of the aggrieved clan, and he was given gifts and shown respect and this former foe, who had caused pain and suffering to people, would live with those whom he had harmed and the peace was made, not just for them but for future generations.

The parties were able to come together, to trade, to marry, to work together and make their lives together. The dispute was over and peace and harmony was restored.

I seek the same outcome. My people seek that same outcome. I know we are a part of this nation I want to be a part of this nation but I want to have my peoples grievances settled in a calm and proper way. And then I want unity and togetherness a shared future. A rightful place.

This is what constitutional recognition seeks to achieve for Australia. This is the work of the Referendum Council and all the delegates who came together at Uluru to make a united call for serious constitutional reform. This must now also be the work of all Australians. The parties must now sit down together and talk calmly and agree on a path forward.

In the old days the clan leaders would send a gift of cycad bread to the other clan to request a meeting in a peaceful way. So, too, is the final Referendum Council report a sign of friendship and a call to make peace. The essays in this book also form part of that process these words are a gift to us all. They inform us and guide us as we seek the real outcome of makarrata: peace and harmony in our shared future.

Uluru Statement from the Heart

W e, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from time immemorial, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or mother nature, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australias nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future. These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

Next page