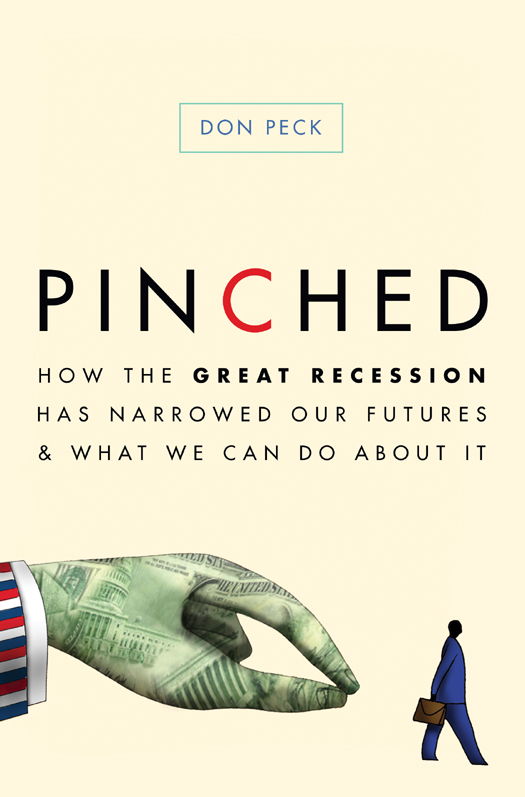

Copyright 2011 by Don Peck

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

eISBN: 978-0-307-88654-5

Jacket design by W. G. Cookman

Jacket illustration by Kevin Orvidas/Getty Images

v3.1

We are unsettled to the very roots of our being. There isnt a human relation, whether of parent and child, husband and wife, worker and employer, that doesnt move in a strange situation. There are no precedents to guide us, no wisdom that wasnt made for a simpler age. We have changed our environment more quickly than we know how to change ourselves.

W ALTER L IPPMANN ,

Drift and Mastery: An Attempt to Diagnose the

Current Unrest, 1914

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

W HAT LIES ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE G REAT R ECESSION? Nearly three years after the crash of 2008, the American economy has partly recovered, the market has long since rallied, and Wall Street is back from the dead and newly flush. In many of the nations most affluent suburbs and in the centers of its most dynamic cities, life has gone back to something like normal. Yet outside these islands of affluence, jobs remain scarce and the housing market devastated. Millions of families have fallen out of the middle class, and millions of young adults have found themselves unable to climb up into it. Throughout much of the country, debilitating weakness lingers on.

This book is about the enduring impact that the Great Recession will have on American life. What we know from three comparable economic calamitiesthe panic of the 1890s, the Great Depression, and the oil-shock recessions of the 1970sis that periods like this one deepen societys fissures and eventually transform the culture. The social changes that occurred in the midst of these other major downturns lasted decades beyond the end of the crises themselves. The Great Recession will prove no different. The crash has already shifted the course of the U.S. economy, and its continuing reverberations have changed the places we live, the work we do, our family ties, and even who we are. But the recessions most significant and far-reaching ramifications still lie in the future.

If something cannot go on forever, the late economist Herbert Stein famously said, it will stop. The Great Recession put an end to many unsustainable habits, most notably a decade-long mania for credit spending, fueled by a national housing bubble of epic proportions. But by deflating that bubbleand halting all the optimistic spending that had gone along with itthe recession also laid bare other, much deeper economic trends: the growing concentration of wealth among a tiny sliver of Americans; the thinning of the middle class; the diverging fortunes of different regions, cities, and communities. Indeed, as periods like this one usually do, the recession has accelerated these trends.

When, and for that matter how, will the United States fully recover? These are urgent and complex questions, and in this book I will do my best to answer them. But in truth, societies never just recover from downturns this severe. They emerge from them different than they were beforestronger in some ways, weaker in others, and in many respects simply transformed.

Across American society, old, familiar patterns of work, family, and everyday life have been disrupted and remade since the crash. Intense economic forces are remolding the American experience and redefining the American Dream.

The economic rift between rich Americans and all other Americans is gaping wider as the former recover and the latter do not. And in the recessions aftermath, a cultural rift has grown, too: for the very rich, in particular, global affinities and global ambitions are quickly supplanting national ties and national concerns. Increasingly, the very rich see themselves as members of a global elite with whom they have more in common than with other classes of Americans. Politically influential and economically powerful, they are becoming a separate nation with its own distinct goals.

The fortunes of different places also are diverging quickly. High-powered areas like New York, Silicon Valley, and Washington, DC, are putting the recession behind them. Former oases for aspiring middle-class AmericansPhoenix, Tampa, Las Vegashave been exposed as mirages. Nationwide, newer suburbs on the exurban fringe appear to be in irreversible decline, and the families living in them are stuck and struggling. As a result, middle-class mores and lifestyles are being transformedand so are the futures of middle-class children.

Women are fast becoming the essential breadwinners and authority figures in many working-class familiesa historic role reversal that is fundamentally changing the nature of marriage, sex, and parenthood. Working-class men, meanwhile, are losing their careers, their families, and their way. A large, white underclass, predominantly male, is formingalong with a new politics of grievance. Both will shape the nations character long after the recession is fully over.

The Millennial Generation, the largest generation in American history and perhaps the most audacious, is sinking. Many twentysomethings will emerge from the Great Recession with their earning power permanently reduced, their confidence dimmed, and their ideals profoundly changed.

Some of the transformations under way are direct results of the recessions severity. When jobs are scarce, incomes flat, and debts heavy for protracted periods, people, communities, and even whole generations can be left permanently scarred. And some of these changes are products of economic forces that predate the recession but have been strengthened by it. In the end, the crisis cannot be separated from the technological revolution that was under way in the United States for years beforehand: it was in some respects the denouement of that revolution, and the related revolution in global trade. The global economy is evolving at an unprecedented pace, and while some Americans and many U.S. businesses have adapted well, the country as a whole has not. It will remain economically vulnerable and socially divided until it does.

Pinched begins with some history, explaining why the Great Recession stands apart from the downturns that immediately preceded it, and detailing what we can learn from the aftermath of other crashes, further back in Americas history, that more closely recall this one. The heart of the book describes how this period has changed the character and future prospects of different people and communities throughout the country: striving middle-class families, inner-city youth, newly minted college graduates, blue-collar men, affluent professionals, elite financiers. When they linger long enough, hard times and deep uncertainty can greatly alter peoples values, social relationships, and even personal identity. Around the nation, some of those changes are just now becoming visible.

The final section of the book describes how our politics and national character are changing as a result of economic weaknessand how we can recover from this period and build a stronger, more resilient economy and society. Part of the answer lies in smarter, more creative, and more decisive government actions. And part lies in a renewed private commitment to civic responsibility and community life. This period of globalization and disruptive technological change, distilled and made toxic by the Great Recession, has left our social fabric tattered. We can restore it, both through public action and through our own daily choices.