House of Debt

House of Debt

How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again

Atif Mian and Amir Sufi

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Atif Mian is professor of economics and public policy at Princeton University.

Amir Sufi is the Chicago Board of Trade Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2014 by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi

All rights reserved. Published 2014.

Printed in the United States of America

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-08194-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-13864-0 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226138640.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mian, Atif, 1975 author.

House of debt: how they (and you) caused the Great Recession, and how we can prevent it from happening again / Atif Mian and Amir Sufi.

pages; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-08194-6 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-13864-0 (e-book) 1. Financial crisesUnited States. 2. Consumer creditUnited States. 3. Debtor and creditorUnited States. 4. ForeclosureUnited States. 5. Financial crisesPrevention. 6. ForeclosureUnited StatesPrevention. 7. Global Financial Crisis, 20082009. I. Sufi, Amir, author. II. Title.

HB3743.M53 2014

330.9730931dc23 2013049671

o This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To our parents, for always being there

To Saima and Ayesha

Contents

Selling recreational vehicles used to be easy in America. As a button worn by Winnebago CEO Bob Olson read, You cant take sex, booze, or weekends away from the American people. But things went horribly wrong in 2008, when sales for Monaco Coach Corporation, a giant in the RV industry, plummeted by almost 30 percent. This left Monaco management with little choice. Craig Wanichek, their spokesman, lamented, We are sad that the economic environment, obviously outside our control, has forced us to make... difficult decisions.

Monaco was the number-one producer of diesel-powered motor homes. They had a long history in northern Indiana making vehicles that were sold throughout the United States. In 2005, the company sold over 15,000 vehicles and employed about 3,000 people in Wakarusa, Nappanee, and Elkhart Counties in Indiana. In July 2008, 1,430 workers at two Indiana plants of Monaco Coach Corporation were let go. Employees were stunned. Jennifer Eiler, who worked at the plant in Wakarusa County, spoke to a reporter at a restaurant down the road: I was very shocked. We thought there could be another layoff, but we did not expect this. Karen Hundt, a bartender at a hotel in Wakarusa, summed up the difficulties faced by laid-off workers: Its all these people have done for years. Whos going to hire them when they are in their 50s? They are just in shock. A lot of it hasnt hit them yet.

Northern Indiana felt the pain early, but it certainly wasnt alone. The Great American Recession swept away 8 million jobs between 2007 and 2009. More than 4 million homes were foreclosed. If it werent for the Great Recession, the income of the United States in 2012 would have been higher by $2 trillion, around $17,000 per household.

Just like workers at the Monaco plants in Indiana, innocent bystanders losing their jobs during recessions often feel shocked, stunned, and confused. And for good reason. Severe economic contractions are in many ways a mystery. They are almost never instigated by any obvious destruction of the economys capacity to produce. In the Great Recession, for example, there was no natural disaster or war that destroyed buildings, machines, or the latest cutting-edge technologies. Workers at Monaco did not suddenly lose the vast knowledge they had acquired over years of training. The economy sputtered, spending collapsed, and millions of jobs were lost. The human costs of severe economic contractions are undoubtedly immense. But there is no obvious reason why they happen.

There has been an explosion in data on economic activity and advancement in the techniques we can use to evaluate them, which gives us a huge advantage over Keynes and his contemporaries. Still, our goal in this book is ambitious. We seek to use data and scientific methods to answer some of the most important questions facing the modern economy: Why do severe recessions happen? Could we have prevented the Great Recession and its consequences? How can we prevent such crises? This book provides answers to these questions based on empirical evidence. Laid-off workers at Monaco, like millions of other Americans who lost their jobs, deserve an evidence-based explanation for why the Great Recession occurred, and what we can do to avoid more of them in the future.

Whodunit?

In A Scandal in Bohemia, Sherlock Holmes famously remarks that it is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.the evidence, but our approach must resemble Sherlock Holmess. Lets begin by collecting as many facts as possible.

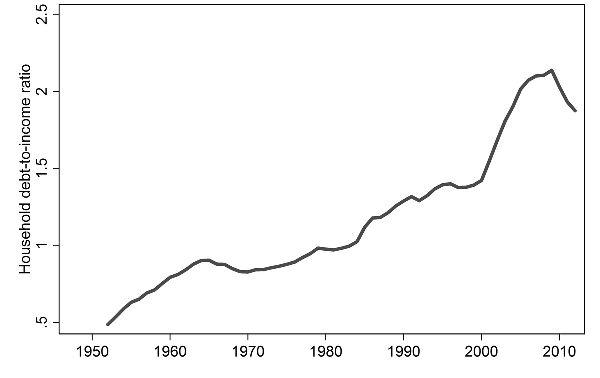

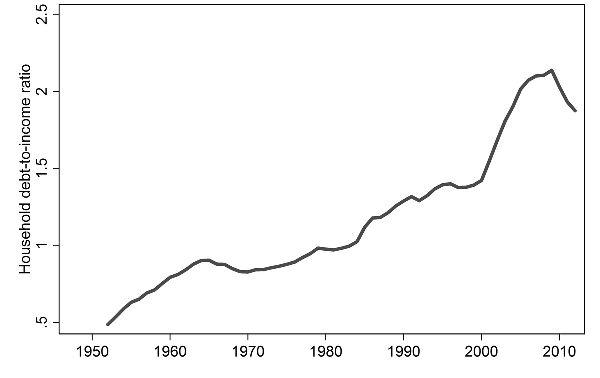

Figure 1.1: U.S. Household Debt-to-Income Ratio

When it comes to the Great Recession, one important fact jumps out: the United States witnessed a dramatic rise in household debt between 2000 and 2007the total amount doubled in these seven years to $14 trillion, and the household debt-to-income ratio skyrocketed from 1.4 to 2.1. To put this in perspective, shows the U.S. household debt-to-income ratio from 1950 to 2010. Debt rose steadily to 2000, then there was a sharp change.

Using a longer historical pattern (based on the household-debt-to-GDP [gross domestic product] ratio), economist David Beim showed that the increase prior to the Great Recession is matched by only one other episode in the last century of U.S. history: the initial years of the Great Depression. Such a massive increase in mortgage debt even swamps the housing-boom years of 20002007.

The rise in installment financing in the 1920s revolutionized the manner in which households purchased durable goods, items like washing machines, cars, and furniture. Martha Olney, a leading expert on the history of consumer credit, explains that the 1920s mark the crucial turning point in the history of consumer credit. For the first time in U.S. history, merchants selling durable goods began to assume that a potential buyer walking through their door would use debt to purchase. Societys attitudes toward borrowing had changed, and purchasing on credit became more acceptable.

With this increased willingness to lend to consumers, household spending in the 1920s rose faster than income. And as households loaded up on debt to purchase new products, they saved less. Olney estimates that the personal savings rate for the United States fell from 7.1 percent between 1898 and 1916 to 4.4 percent from 1922 to 1929.

So one fact we observe is that both the Great Recession and Great Depression were preceded by a large run-up in household debt. There is another striking commonality: both started off with a mysteriously large drop in household spending. Workers at Monaco Coach Corporation understood this well. They were let go in large part because of the sharp decline in motor-home purchases in 2007 and 2008. The pattern was widespread. Purchases of durable goods like autos, furniture, and appliances plummeted early in the Great Recessionbefore the worst of the financial crisis in September 2008. Auto sales from January to August 2008 were down almost 10 percent compared to 2007, also before the worst part of the recession or financial crisis.

Next page