Philip H. Howard - Concentration and Power in the Food System

Here you can read online Philip H. Howard - Concentration and Power in the Food System full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Bloomsbury UK, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Concentration and Power in the Food System

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury UK

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Concentration and Power in the Food System: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Concentration and Power in the Food System" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Concentration and Power in the Food System — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Concentration and Power in the Food System" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Concentration and

Power in the Food

System

Contemporary Food Studies: Economy, Culture and Politics

Series Editors: David Goodman and Michael K. Goodman

ISSN: 20581807

This interdisciplinary series represents a significant step toward unifying the study, teaching, and research of food studies across the social sciences. The series features authoritative appraisals of core themes, debates and emerging research, written by leading scholars in the field. Each title offers a jargon-free introduction to upper-level undergraduate and postgraduate students in the social sciences and humanities.

Kate Cairns and Jose Johnston, Food and Femininity

Peter Jackson, Anxious Appetites: Food and Consumer Culture

Philip H. Howard, Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What We Eat?

Further titles forthcoming

Concentration

and Power

in the Food

System

Who Controls

What We Eat?

Philip H. Howard

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Figures

Tables

Boxes

I am incredibly fortunate to have worked at three universities with numerous food and agriculture scholars: the University of Missouri, University of California at Santa Cruz, and Michigan State University. Each of these experiences played an important role in development of ideas in this book.

Missouri had a formative influence, particularly my experience studying food industry concentration with Bill Heffernan and Mary Hendrickson. My views were also shaped by other members of the Sociology of Agriculture Working Group, including Beth Barham, Jere Gilles, John Green, Bob Gronski, Judy Heffernan, John Ikerd, David Lind, Anna Kleiner, Bryce Oates, Andy Raedeke, and Sandy Rikoon, In addition, I benefited from interactions with former members, especially Doug Constance and Leland Glenna.

Participating in the Agro-Food Studies Working Group in Santa Cruz was an unparalleled experience, providing me the opportunity to participate in the exchange of ideas between Patricia Allen, Chris Bacon, Melanie DuPuis, Margaret Fitzsimmons, Bill Friedland, Brian Fulfrost, Tara Pisani Gareau, David Goodman, Mike Goodman, Julie Guthman, Jill Harrison, Hilary Melcarek, Albie Miles, Katie Monsen, Dustin Mulvaney, Jan Perez, Diana Stuart, and Keith Warner.

At Michigan State University I continued to learn much from colleagues, including Jim Bingen, Larry Busch, Laura DeLind, Mike Hamm, Craig Harris, Dan Jaffee, Paul Thompson, Kyle Whyte, David Wright, and Wynne Wright. Michigan State University also granted me a sabbatical leave in 20132014 to complete this manuscript.

I wish to thank University of Utah, Division of Nutrition for hosting me during this sabbatical, as well as providing opportunities to refine ideas through seminars and guest lectures. Special thanks go to Sally and Howard Ogilvie for important contributions to this project and Ginger Ogilvie for her tremendous support and patience. Finally, I thank series editors David Goodman and Mike Goodman for pointing me to many relevant resources and providing extremely helpful suggestions for improvement.

Power is not a means, its an end.

OBrien (Nineteen Eighty-Four)

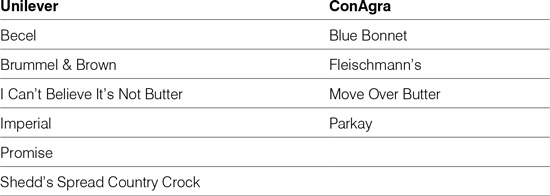

If you go into a typical grocery store in the United States and make your way back to the margarine case, you will probably see approximately a dozen different brands. If you look very closely at the packaging, however, you may find a small seal, which signifies the majority of these are owned by either Unilever or ConAgra (difficult to discern that scores of these, as well as more than half of US sales, are controlled by only three companies: Gallo, The Wine Group, and Constellation (Howard et al. 2012). In nearly every other stage of the food system, including retailing, distribution, farming and farm inputs (e.g., seeds, fertilizers, pesticides), a limited number of firms or operations tend to make up the vast majority of sales.

Table 1.1 Ownership of margarine brands

Is this a problem? An increasing number of people argue that indeed it is: the firms that dominate these industries are criticized for a long list of purported negative impacts on society and the environment. Just a few examples include:

Walmart, which controls 33 percent of US grocery retailing, is challenged for exploiting its suppliers, taking advantage of taxpayer subsidies, and paying extremely low worker wages.

McDonalds, which controls more than 18 percent of US fast food sales, is also critiqued for extremely low wages, as well as the negative health consequences and environmental impacts of its products.

Tyson, which controls more than 17 percent of US chicken, pork, and beef processing is reproached for its pollution, poor treatment of farmers, and contributions to the decline of rural communities.

Monsanto, which controls 26 percent of the global commercial seed market, is denounced for its influence on government policies, spying on farmers it suspects of saving and replanting seeds, and the environmental impacts of herbicides tied to these seeds.

These impacts tend to disproportionately affect the disadvantagedsuch as women, young children, recent immigrants, members of minority ethnic groups, and those of lower socioeconomic statusand as a result, reinforce existing inequalities (Allen and Wilson 2008). Like ownership relations, the full extent of these consequences may be hidden from public view.

This book seeks to illuminate which firms have become the most dominant, and more importantly, how they shape and reshape society in their efforts to increase their control. These dynamics have received insufficient attention from academics and even critics of the current food system. The power of dominant firms extends far beyond narrow economic boundaries, for example, providing them with the ability to damage numerous communities and ecosystems in their pursuit of higher than average profits. The social resistance provoked by these negative consequences is another area that is less visible to the majority of the population. When such resistance is evident at all, it frequently appears insignificant, failing to challenge the direction of current trends. Even very small movements, however, may influence which firms end up winners or losers or close off particular avenues for growth. These accomplishments also suggest potential limits and therefore the possibility that dominant firms may experience much greater threats to their power in the future.

Increasing concentration

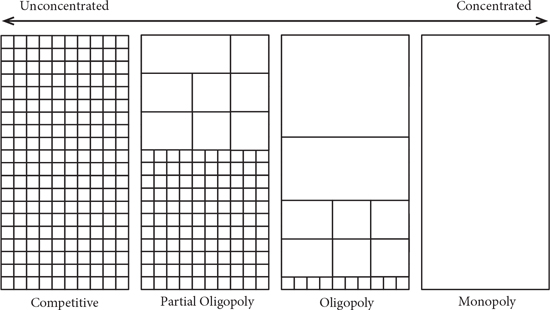

Concentration is a term used to describe the composition of a given market, and especially its potential impacts on competition. At one end of the spectrum are markets that are described as unconcentrated or fragmented, which economists consider to be freely competitive (their prices but lack the power to significantly reduce competition, as is the case with oligopolies. The word monopoly is derived from the Greek words for single (mono) and seller (polein), but concentrated markets may also occur among buyers, as found in a monopsony or oligopsony (derived from the Greek word for buy, opsna).

Figure 1.1 Levels of market concentration.

Each rectangle represents a single, hypothetical firm, with size proportional to market share.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Concentration and Power in the Food System»

Look at similar books to Concentration and Power in the Food System. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Concentration and Power in the Food System and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.