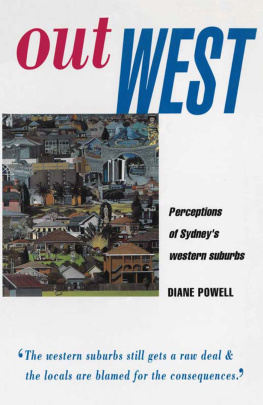

Out West

Perceptions of Sydneys

western suburbs

Diane Powell

ALLEN & UNWIN

For Tutti

Diane Powell 1993

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved.

First published in 1993

Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd

9 Atchison Street, St Leonards

NSW 2065 Australia

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Powell, Diane (Diane Leslie).

Out west: perceptions of Sydneys western suburbs.

Bibliography.

ISBN 1 86373 503 8.

eISBN 978 1 74269 676 8

1. Western Sydney (N.S.W)Social conditions. I. Title

307.76099441

General editors foreword

Nowadays the social and anthropological definition of culture is probably gaining as much public currency as the aesthetic one. Particularly in Australia, politicians are liable to speak of the vital need for a domestic film industry in promoting our cultural identityand they mean by cultural identity some sense of Australianness, of our nationalism as a distinct form of social organisation. Notably, though, the emphasis tends to be on Australian film (not popular television); and not just any film, but those of quality. So the aesthetic definition tends to be smuggled back inon top of the kind of cultural nationalism which assumes that Australia is a unified entity with certain essential features that distinguish it from Britain, the USA or any other national entities which threaten us with cultural dependency.

This series is titled Australian Cultural Studies, and I should say at the outset that my understanding of Australian is not as an essentially unified category; and further, that my understanding of cultural is anthropological rather than aesthetic. By culture I mean the social production of meaning and understanding, whether in the inter-personal and practical organisation of daily routines or in broader institutional and ideological structures. I am not thinking of culture as some form of universal excellence, based on aesthetic discrimination and embodied in a pantheon of great works. Rather, I take this aesthetic definition of culture itself to be part of the social mobilisation of discourse to differentiate a cultural lite from the mass of society.

Unlike the cultural nationalism of our opinion leaders, Cultural Studies focuses not on the essential unity of national cultures, but on the meanings attached to social difference (as in the distinction between elite and mass taste). It analyses the construction and mobilisation of these distinctions to maintain or challenge existing power differentials, such as those of gender, class, age, race and ethnicity. In this analysis, terms designed to socially differentiate people (like lite and mass) become categories of discourse, communication and power. Hence our concern in this series is for an analytical understanding of the meanings attached to social difference within the history and politics of discourse.

Diane Powells book on the western suburbs of Sydney examines the history and politics of discourse head on: not only in regard to the profits there were for city elites and dominant culture, but also in the act of writing the book itself. Could I, Powell asks, speak as a woman from the western suburbs when I was now a city dweller? Looking for an answer to that question takes Powell on a valuable excursion through the field of ethnography where, as she argues, the enquirer and the informant exist in a structured social relationship, with different subjective positions and cultural interests. It is important not to overlook power relations in ethnographys always unequal exchange. Examining a number of current ethnographic theorists and critics, Powell insists that there can be no objective observational position outside the domain of power. Consequently her own voice as westie and as urban intellectual consistently obtrudes, and must be reflexively exposed, in her discourse. Diane Powells book certainly asks the right questions in relation to her representation of the urban elites representation of the western suburbs. It also takes much further our knowledge of the construction of the westie stigma in public and media discourse, adding the dimension of regional division to those of class, gender, race and ethnicity discussed in other books of the series.

Culture, as Fiske, Hodge and Turner say in Myths of Oz, grows out of the divisions of society, not its unity. It has to work to construct any unity that it has, rather than simply celebrate an achieved or natural harmony. Australian culture is then no more than the temporary, embattled construction of unity at any particular historical moment. The readings in this series of Australian Cultural Studies inevitably (and polemically) form part of the struggle to make and break the boundaries of meaning which, in conflict and collusion, dynamically define our culture.

JOHN TULLOCH

Contents

Tables

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

As usual with works of this kind, a vast number of people have helped in various ways throughout its evolution; I thank all of you. Special thanks go to friends, family and workmates for their moral support and tolerance of my social lapses, in particular Madalena (Tutti) Powell, Claire Allen and Tony Mitchell.

Then there are the many present and past residents and workers of the west and south-west who shared their memories and experiences of life with me, in particular Silvia Dal Santo, Kay Ferrington, Shannon Simons, Patricia Parker, Nick Tantaro, Sandra Sanchez, Brett Barrett, Jenny Barrett, Pam Newsome and Ken Canning. I would also like to thank the Cabramatta Community Centre, Parramatta Regional Public Tenants Council, Mount Druitt and the . Thanks are also due to Ann Curthoys, John Docker, Paul Gillen and John Tulloch who read and commented on earlier drafts.

I am grateful to Biaba Berzins for permission to reproduce her letter to the Sydney Morning Herald, a quote from which appears on the cover, and to Claudio Ramos and Steven McMullan whose photograph appears on page 121. I also thank the Sydney Morning Herald, Telegraph Mirror, Tracks, State Library of New South Wales, Cabramatta Library, Penrith Library, Sound Unlimited and Western Regional Information and Research Service for permission to reproduce material. Every effort has been made to source and acknowledge the copyright material used. In the case of any omissions, I would be pleased to make suitable acknowledgements in future editions.

Introduction

For most of my life I was one of those people referred to as stupid enough to live west of Parramatta by the federal president of the Australian Association of Surgeons (SMH 26.2.91). Living through the postwar history and development of the area, I have seen it transformed from a semi-rural area of market gardens and poultry farms, through its dynamic years as a new growth area, into the culturally rich and diverse rim of Sydney that it is today. At some stage during that time I became aware that some people looked down on residents of the western suburbs. It wasnt just the jokes about living out in the sticks, there was a different edge to the surprised looks when I revealed where I lived, making me feel self-conscious, and distinctly other. Involvement in local community activities, with the wider Sydney cultural scene, with feminism and tertiary education sharpened rather than blurred the distinctions. For many years I felt a mixture of curiosity, surprise and indignation at peoples reactions, and at always having to explain and justify living in the outer west. Nobody, it seemed, asked people living at Pymble or Frenchs Forest, Why do you live