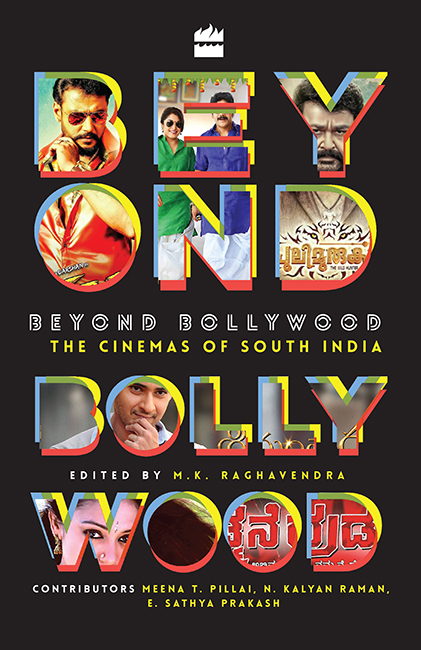

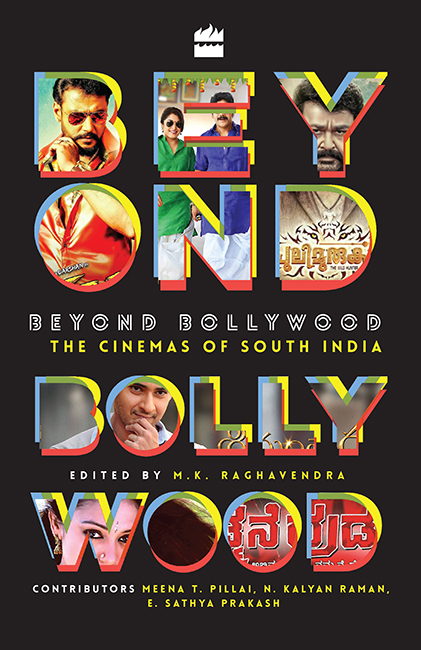

Table of Contents

BEYOND

BOLLYWOOD

The Cinemas of South India

Edited by

M.K. RAGHAVENDRA

Essays by

ELAVARTHI SATHYA PRAKASH

M.K. RAGHAVENDRA

N. KALYAN RAMAN

MEENA T. PILLAI

HarperCollins Publishers India

CONTENTS

M.K. RAGHAVENDRA

Mumbai and Chennai

Most of the significant writing on Indian cinema has focused on Hindi popular cinema, or Bollywood as it has now come to be called, and this attention is asymmetric in more than one way. In the first place, a majority of the films made in India are not made in the Hindi language and, secondly, the term Bollywood presumes that Bombay has been the sole spot where Hindi popular cinema is produced. The figures (for 2012) for the number of films indicate that Tamil cinema occupies the first spot in India and Telugu the second, while Hindi films have actually been relegated to third spot.

As regards the production of Hindi films, Madras (now Chennai) has had a history of making Hindi films and most of the top Hindi heroes of the 1950s and 60s worked for film production houses there. Dilip Kumars Azaad (1955), directed by S.M. Sriramulu Naidu and a remake of the Tamil film Malaikkallan (1954), was a big hit across India, and this is only one instance in a whole range; Aamir Khans blockbuster Ghajini (2008), directed by A.R. Murugadoss, is another. There has of late been a series of Bollywood blockbusters, many starring Salman Khan, which originated in languages of the south and were remade in Hindi.

Though this contention introduces an element of subjectivity into the observations, it is also on record that the studios in Madras/Chennai were traditionally run on more professional lines than those in Bombay/Mumbai. This being the case, the question arises as to why Bombay/Mumbai has been considered the centre of film production in India, and the reason may be the concentration of media houses there, which have lavished more attention on that citys relationship with the glamorous film world.

If this explains the greater amount of attention given to Mumbai over Chennai, another question is why Hindi-language cinema has more serious scholarship dedicated to it than the other-language cinemas. The reason for this is evidently that Hindi mainstream cinema has been a national cinema in a way that regional-language cinemas have not which is that it has endeavoured to place itself in the position of a non-local cinema within India, by dealing with non-local concerns. One might not, for instance, be questioned if one were to describe Mother India (1957) or Upkaar (1968) or Lagaan (2001) as national films because they seem to address issues which are not local, despite concentrating their action in certain parts of north India.

The nation imagined by Hindi cinema has always been asymmetric and, if it was once dominated by the cow belt, it is now increasingly centred on the metropolitan city usually Mumbai and sometimes Delhi, but rarely Kolkata or Chennai. Still, the sense that Hindi cinema is national in a unique way makes it of greater academic interest to those interested in India, its society and its politics, rather than in specific parts of it. At the same time, the fact that Hindi cinema addresses a larger territory in spatial terms, and needs to do so without causing local annoyance, leaves it bland, without much of the gusto of the regional cinemas. As an instance, the Kannada films of Upendra such as A (1997) often display the raw aggression of toilet graffiti and can make genteel spectators apprehensive about what they could be seeing. But there is also a huge amount of variety in south Indian cinema: Malayalam films are more subdued (rather than bland) and this is because their emotional undercurrents, though deep, are subtler and held in check.

To use semiotic parlance, regional-language cinema is richer than Bollywood in signifiers and explicating its tendencies is hence more of a challenge. It can be argued that the regional-language popular cinemas offer greater rewards to the interpretive scholar than the Hindi film because they address local concerns as well as national ones and take overlapping identities the regional one based on language as well the national one into consideration in addressing their chosen constituencies. South India complicates matters further because the same directors (who tend to be multilingual) often work in more than one language cinema and understand different constituencies as their own. A Kannada remake is not simply a Tamil films dialogues translated into Kannada, since the specific concerns of their respective audiences need to be addressed separately. A remake has to tailor itself to meet new representational/social needs specific to another public.

History, Celebration, Social Documentation and Interpretation

The essays in this book are mostly given to popular cinema and, generally speaking, five main strategies are acknowledged in the way the scholar-critic approaches popular culture. The first strategy attempts to find the terms of high culture where you least expect them. The second approach places its emphasis on the aspects of social reality that are unavailable to high art. The third refuses to analyse and opts instead for an enthusiastic study of detail as the foundation for evaluation. In the fourth, the hedonistic approach, the problems with the popular are evaded by concentrating exclusively on the pleasure deriving from it. The fifth method usually employed by academics partial to psychoanalysis and methods deriving from structuralism or cultural studies chooses to deal with the division between high and popular culture by dissolving it and declining to differentiate among the objects of study on the basis of such a division. When the purpose of an essay is to grapple with a whole body of cinema, this translates into four main approaches which can be termed historical, celebratory, akin to social document and/or interpretive, with further divisions under them. Interpretation, for instance, could either adopt a theory-down approach (relying usually on psychoanalysis and/or post-structuralism) or be more empirical.

A history of cinema, one may contend, is not a chronological listing of films but implies some acknowledgement of causation linking the categories of films, the generic and thematic choices to the technological advances, policies as well as ground-level developments in the production and distribution of films. A celebration often overlaps with a history because of its reliance on chronology but, rather than emphasizing causal connections, it dwells on detail in the achievements of the film industry. A social document approach might treat cinema as evidence of some kind, possibly of mores and ideologies over a period. An interpretative approach has its interest less in cinema as cinema than in the social conventions and transformations that it charts, unwittingly or wittingly. This means that it is likely to be more speculative than the social document approach, even if its interest is in society. Needless to add, it is not easy to keep the four categories apart: a chronological approach is the most cogent one, and to those fascinated by cinema, an element of celebration is unavoidable; one also does not find cinema worthy of celebration unless one has an idea of its meaning. What it means can itself be apparent or covert and needing to be extracted; and the dividing line between the overt and the covert can also become quite indistinct.

The Essays in the Book

The essays in this book provide accounts of only the four best-known cinemas of south India, since there are other smaller cinemas like those in Konkani, Tulu and the Kodava dialects. Sathya Prakashs essay, which is the story of Telugu cinema from an aficionados viewpoint, looks at it as the biography of the Telugu film industry the directors, producers and stars as well as the socio-political developments which facilitated film production over several decades. It pays attention to the achievements of the pioneers in the face of difficulties and can hence be termed celebratory on this account and in its emphasis on detail. Social issues such as caste, political commitments and persuasions also played a role in Telugu cinema and the essay is sensitive to many of these aspects, as well as to the role of political players in its history like local rajas and zamindars in the colonial period and elected leaders after 1947. It also does something which many find difficult: it finds a place for the film song, especially the lyrics, in the account, an aspect usually excluded from film study.