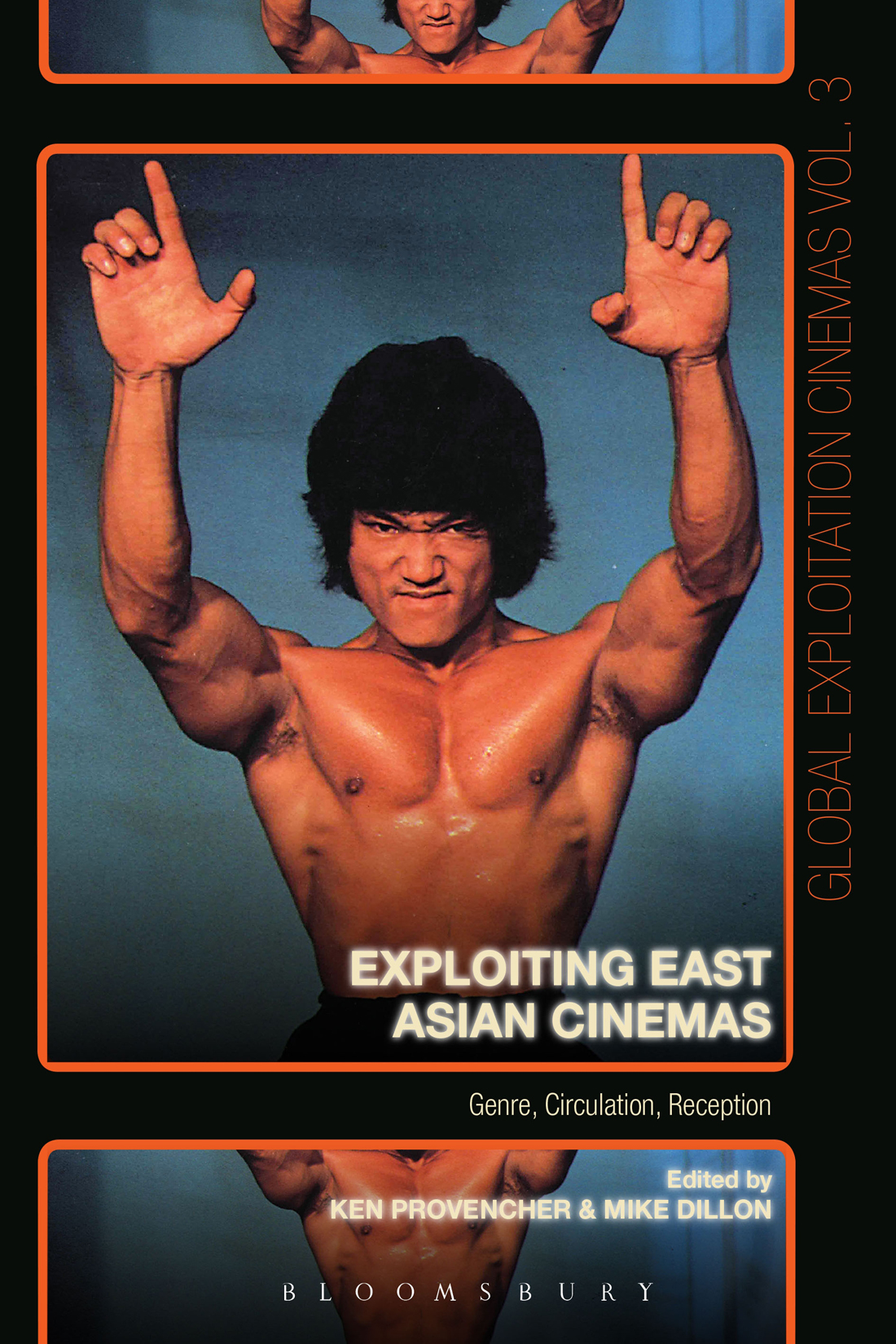

Exploiting East Asian Cinemas

Global Exploitation Cinemas

Series Editors

Johnny Walker, Northumbria University, UK

Austin Fisher, Bournemouth University, UK

Editorial Board

Tejaswini Ganti (New York University, USA)

Joan Hawkins (Indiana University, USA)

Kevin Heffernan (Southern Methodist University, USA)

I. Q. Hunter (De Montfort University, UK)

Peter Hutchings (Northumbria University, UK)

Ernest Mathijs (University of British Columbia, Canada)

Constance Penley (University of California, Santa Barbara, USA)

Eric Schaefer (Emerson College, USA)

Dolores Tierney (University of Sussex, UK)

Valerie Wee (National University of Singapore, Singapore)

Also in the Series:

Disposable Passions: Vintage Pornography and the Material Legacies of Adult Cinema , by David Church

Grindhouse: Cultural Exchange on 42nd Street, and Beyond , edited by Austin Fisher & Johnny Walker

Exploiting East Asian Cinemas

Genre, Circulation, Reception

Edited by

Ken Provencher and Mike Dillon

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

Kenneth Chan

Steven Rawle

Ken Provencher

Man-Fung Yip

Tom Mes

Mila Zuo

Elena del Ro

Hye Seung Chung and David Scott Diffrient

Jun Okada

Kyu Hyun Kim

Video-game screen interface in Tai Chi Zero (2012) fight sequence. |

The fearsome lizard design of Godzilla in King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) |

The friendlier design of the heroic 1970s Godzilla, with Jet Jaguar |

Toys in Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971) |

Algren (Tom Cruise) and Seibei (Sanada Hiroyuki) have replaced the husbands they defeated in The Last Samurai (2003) and Twilight Samurai (2002). |

Bruce Lees Clone: Dragon Lee |

Double exploitation: Dragon Lee and Bruce Leung |

The cut-and-paste method: Splicing footage from disparate sources in Ninja the Protector (1986). |

The robotic kickboxer in Rings Untouchable 1990. |

The Cat-insignia in Catman in Lethal Track (1990) looks similar to the logo of Yamato Transport |

Fan Bingbing symbolizing the homosocial gift in Lost in Thailand (2012). |

Bao Bao (Wang Baoqiang) is decentered and unselfed by Fans beauty in Lost in Thailand reaction shot. |

A beauty close-up on Fan in Cell Phone (2003) |

The scorned wife drinks next to a lifeless statue of a dog in Moebius (2013). |

The teenaged son looks despondent and lonely in a loveless bourgeois home. Moebius |

Moebius s second castration is presented as a detached surgical procedure. |

Takeda Miyuki fi lmed by Hara Kazuo while having sex in Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974 . |

Fourteen-year-old Okinawan bargirl, Chi Chi. Extreme Private Eros |

Alternative titling for Shwa Kaij films. |

The editors wish to thank the Global Exploitation Cinemas Series Editors Johnny Walker and Austin Fisher for their constant enthusiasm and support for this project. We also want to thank all of the contributors for their responsiveness and cooperation throughout the long process of development. Two anonymous readers of our proposal, and one anonymous reader of the completed manuscript, provided us with extremely helpful comments and suggestions. Thanks as well to Dong Hoon Kim.

Everyone at Bloomsbury Academic has been fantastic to work with throughout development and production. We want to thank especially Katie Gallof, our patient and encouraging editor, and Susan Krogulski, who was essential in helping us organize the text and images. Production Editor Lauren Crisp and Designer Louise Dugdale were also an enormous help at Team Bloomsbury.

Julian Stringer

Having spent too much time laboring at his job, the protagonist has turned into a poor husband and a neglectful father, but because he is anxious to win back the affection of his daughter, he agrees to accompany her on a journey to visit her mother. On departing the railway station, however, the two find themselves in a difficult situationthronged by snarling mutants. Their initiation into combat with these aggressive hybrids turns into an unexampled adventure of trials, atonements, and apotheosis, and in the end there is a return of sortsalbeit a sad one. With escape from the deadly foes within grasp, the father makes the profound discovery that what he actually needs (as opposed to what he wants) is to love his daughter unconditionally. He therefore sacrifices himself for his child, and in so doing reveals that he has been undertaking a double odyssey all alongan outer (visible) one of survival, and an inner (invisible) one toward emotional fulfillment.

The alert reader may recognize in the above description the skeleton plot of Train to Busan ( Busanhaeng ; Yeon, 2016; henceforth Train ), a zombie movie from South Korea that became an international hit at the same time Ken Provencher and Mike Dillon were putting together this stimulating collection of original pieces on Exploiting East Asian Cinemas . It is a film that embodies many of the tendencies of exploitation filmmaking from and about the region analyzed by the numerous contributors to this lively and wide-ranging volume. Train is characterized by violence and sensationalism, elements also emphasized in its global marketing campaigns. The focus throughout its running time is on the shocking, the taboo, or the otherwise transgressiveevidenced, for example, by the ways in which it provides, alongside the customary gore, an emotional outlet for current events via an impolite engagement with thorny aspects of South Korean society such as social protest, the break-up of the family unit, and rigid workplace hierarchies. Also, it blurs the boundaries between the marginal and the mainstream, being a modestly budgeted production that has nevertheless achieved blockbuster status domestically as well as high visibility overseas. Further still, Train feeds the contemporary transnational fad for zombie movies while spawning its own progeny in the form of an animated prequel ( Seoul Station ; Yeon, 2016) and a reported forthcoming English-language remake.

For the present purposes, an additional point of interest is that Train offers a powerful illustration of the (often unremarked) continuities between the specific cultural form under discussion and international storytelling principles. In narrative terms, it is organized in a classic three-act structure. The movie is built on audience interest in, and sympathy for, a central character, Seok-woo (Gong Yoo), who is placed in jeopardy. This man is a socially powerful if emotionally cowardly individual who strives to balance his busy working and family lives, but who comes up against seemingly insurmountable obstacles (the zombies) out of which a struggle ensues. Utilizing the classic triumvirate of commercial audiovisual storytellingcharacter, desire, and conflict Train first presents a problem, introduces an antagonist, and then illustrates the ways in which the initially troublesome situation is resolved. Furthermore, everything happens in real-time and in a continuous space, and the films end is contained in its beginning.