Landmarks

Page list

i

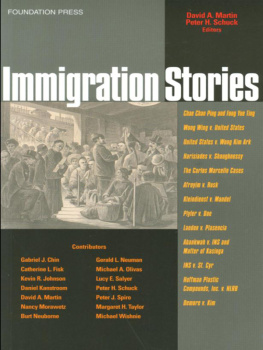

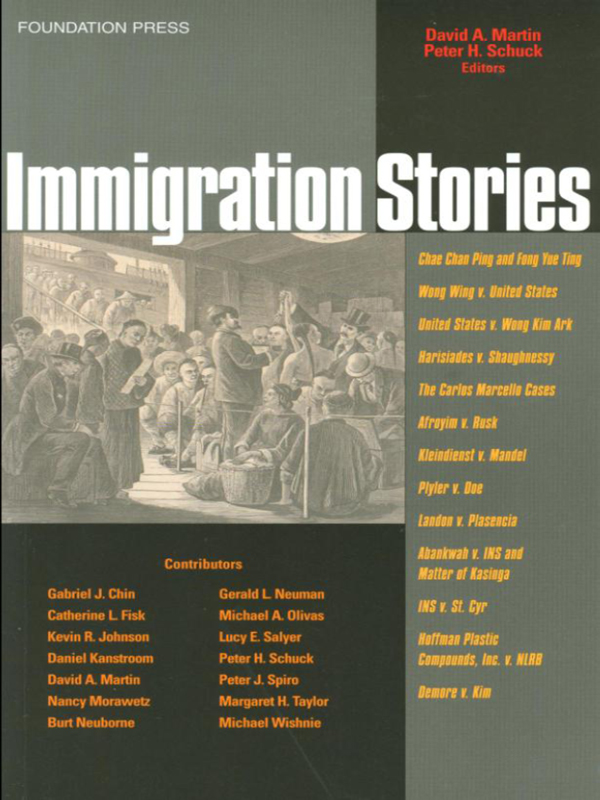

FOUNDATION PRESS

IMMIGRATION STORIES

Edited By

DAVID A. MARTIN

WarnerBooker Distinguished Professor of International Law

Class of 1963 Research Professor

University of Virginia

PETER H. SCHUCK

Simeon E. Baldwin Professor of Law

Yale Law School

ii

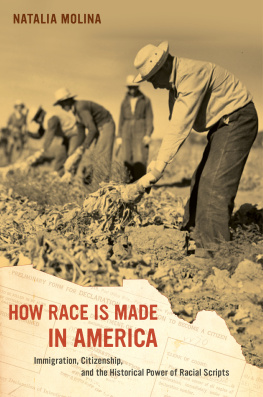

Cover image: Chinese Immigrants at the San Francisco Custom-House, Harpers Weekly, February 3, 1877.

Foundation Press, of Thomson/West, has created this publication to provide you with accurate and authoritative information concerning the subject matter covered. However, this publication was not necessarily prepared by persons licensed to practice law in a particular jurisdiction. Foundation Press is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice, and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. If you require legal or other expert advice, you should seek the services of a competent attorney or other professional.

2005 By FOUNDATION PRESS

395 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

Phone Toll Free 18778881330

Fax (212) 3676799

fdpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 158778873X

iii

IMMIGRATION STORIES

David A. Martin and Peter H. Schuck

Gabriel J. Chin

Gerald L. Neuman

Lucy E. Salyer

Burt Neuborne

Daniel Kanstroom

Peter J. Spiro

Peter H. Schuck

Michael A. Olivas

Kevin R. Johnson

David A. Martin

iv

Nancy Morawetz

Catherine L. Fisk and Michael J. Wishnie

Margaret H. Taylor

v

FOUNDATION PRESS

IMMIGRATION STORIES

*

Introduction

David A. Martin and Peter H. Schuck

Immigration stories help shape how we conceive of ourselves as a nation. At the end of his noted history of multicultural America, Ronald Takaki reflects:

As Americans, we originally came from many different shores, and our diversity has been at the center of the making of America. While our stories contain the memories of different communities, together they inscribe a larger narrative. Filled with what Walt Whitman celebrated as the varied carols of America, our history generously gives all of us our mystic chords of memory.

In an earlier generation, Oscar Handlin opened his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Uprooted , with these words: Once I thought to write a history of the immigrants in America. Then I discovered that the immigrants were America.

Although the American immigration narrative is sometimes rendered as a pure tale of hope, grit, and triumph, a truthful account would include its share of stories of tragedy, shame, conflict, and failure (as Takakis and Handlins works make manifest). This mixed picture of success and setback holds whether viewed from the perspective of the individuals who migrate, the society that receives them, or the government that seeks to regulate the process. And of course this complex story is still unfolding. Since September 11, 2001, we have seen a remarkable reaffirmation of inclusiveness alongside an increased fear of aliens from certain regions associated with terrorist threats.

Given the centrality of immigration to American self-understanding, it is wholly fitting that Immigration Stories should join a new series of vital teaching materials augmenting law school casebooks. The Stories series tells the tales behind leading cases, anchoring them in their historical contexts, revealing the political and litigation strategies that drove them forward, and humanizing the individuals caught up in their toils. (Immigration stories are particularly rich in this human element, owing to the distinctive aspirations and struggles bound up with a decision to migrate.) The series also is meant to analyze the ongoing significance of each of the judicial decisions, as the polity accepts, rejects, or modifies their legal implications.

It is no easy task to select a bakers dozen of the most important, representative, or revealing immigration cases to include in such a volume. As editors, we knew, of course, that we would include cases that depict the Supreme Courts broad deference to the political branches in the immigration realm, the so-called plenary power doctrine. But which cases should we chooseconcerning that seminal doctrine as well as othersand how should we array them, given that many of the most important immigration cases address multiple themes? Ultimately, we decided to present those we selected in chronological order; one who reads from start to finish can gain some sense of the ebb and flow of the immigration case law.

Our book begins, naturally, with the Supreme Courts consideration of the Chinese Exclusion Acts of the 1880s and 1890s, the first sustained assertions of federal immigration control authority. Gabriel Chin describes the fascinating litigation context and the continuing significance of the two cases Chae Chan Ping v. United States (sometimes called the Chinese Exclusion Case ) and Fong Yue Ting v. United States that are regarded as the foundation stones for the plenary power doctrine. In later generations, it was usually war that tested the constitutional limits of the governments plenary power over immigration. We pick up that thread with the Cold War. In Harisiades v. Shaughnessy , in 1952, the government successfully relied on the doctrine to justify deportation of three former members of the Communist Party, all long-time lawful permanent residents, based on a retroactive application of a statute passed after all three had terminated their membership, at least formally. Burt Neuborne relates how various strategic decisions led to the Courts rejection of their constitutional claims under the Ex Post Facto and Due Process clauses and the First Amendment. Twenty years later, the Court in Kleindienst v. Mandel reaffirmed plenary power by overriding First Amendment challenges to the exclusion of a Marxist intellectual, despite the post- Harisiades liberalization of First Amendment doctrine. In recounting that litigation, Peter Schuck shows how the lower courts subsequently exploited a doctrinal loophole left by the Court, which helped give reformers the opening they needed to limit the governments visa-denying discretion. In the chapter on the 2003 case of Demore v. Kim , Margaret Taylor explains how elements of the plenary power doctrinecoupled with the national trauma created by September 11, 2001may have led the Court to countenance an unnecessarily harsh mandatory detention provision despite a precedent from only two years earlier ( Zadvydas v. Davis ) that seemed to presage a more forceful judicial defense of the liberty claims of detained aliens.

Plenary power, however, is not the whole immigration law story. Perhaps influenced by the almost universal academic criticism of the doctrine, the Supreme Court has occasionally reined in the political branches, usually using a distinctively stingy form of statutory constructionwhat Hiroshi Motomura has labeled phantom constitutional normsto defeat the governments broadest claims. At other times, the Court has deployed the Constitution itself to protect aliens or their children against political branch overreaching. INS v. St. Cyr , recounted by Nancy Morawetz, reflects the former approach. Congress tried in 1996 to strip the courts of jurisdiction to consider challenges to removal filed by virtually any alien with a criminal conviction in the United States. The Supreme Court read the law quite narrowly, finding that it allowed the trial courts to entertain habeas corpus petitions filed by such aliens. The ruling resulted in thousands of new hearings.