Preface and Chapter 6 Copyright Black Inc. 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry for print edition:

Quiggin, John.

Zombie economics : how dead ideas still walk among us / John Quiggin.

Economics--History--20th century. Economic policy--History--20th century. Economics.

Preface to the Australian Edition

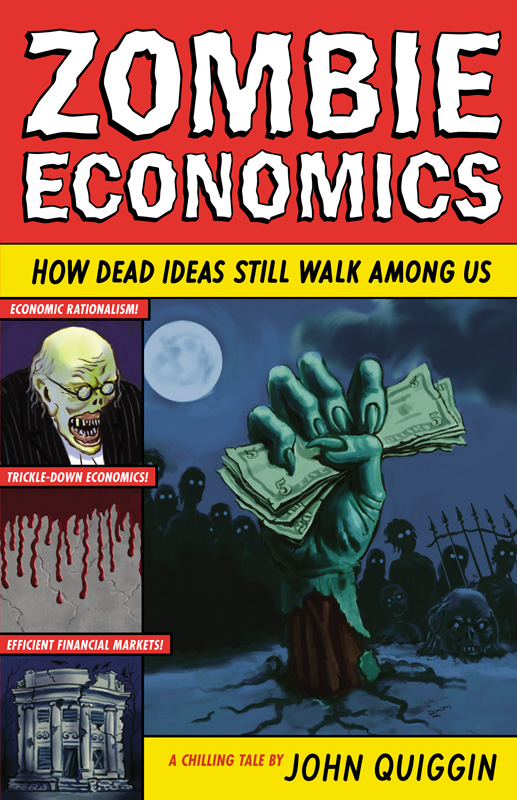

When I started writing Zombie Economics early in 2009, its working title was Dead Ideas . I assumed that the comprehensive failure of the global financial system would permanently discredit the set of ideas that had supported the rise of an unsustainable form of capitalism, in which speculative financial transactions were seen as the ideal guiding mechanism for economic decisions of all kinds. That set of ideas, which I called market liberalism, has been given a variety of names, but in Australia it has usually been known as economic rationalism.

I was not alone in my expectation of a radical change. Kevin Rudds essay in The Monthly , published in February 2009, looked forward to a new era of social democracy. Even more strikingly, Ian Harper, a leading free-market economist and member of the Wallis Committee on financial deregulation, noted the failure of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, on which the Committees reasoning was based.

Yet as soon as the threat of a full-scale economic collapse had passed, the old ideas re-emerged. Like the Bourbons on their return to power after the fall of Napoleon, our leading policymakers, and the commentators who informed them, seemed to have learned nothing and forgotten nothing.

Even though the ideas of the past continue to dominate public debate, they no longer represent a living body of thought. Rather, they are reanimated husks, shuffling and shambling across the political scene, mouthing slogans that no longer have any real meaning. In a word, they are zombies, and hence the title of this book.

Ideas are often presented as if they are eternal truths, or the product of the inspired thinking of a solitary genius. Even in critical accounts, the ideas of market liberalism are often presented as simple errors, or else as transparent fictions designed to protect class interests. The real story is inevitably more complex, involving an interaction between ideology, empirical evidence and the demand for policy solutions to real problems of unemployment and inflation.

One of my central concerns in Zombie Economics has been to explain how classical free-market economics, seemingly discredited by its failure in the Great Depression and by the success of Keynesian social democracy after 1945, re-emerged as the market liberalism that has dominated the thinking of policy elites since the 1970s.

The central aim of the book is to trace the life-cycle of these zombie ideas from their emergence (at least in their modern form) as a reaction against Keynesian social democracy, through to their failure in the Global Financial Crisis. Only by understanding the birth and life of these ideas, as well as the reasons for their death, can we bury them once and for all and move on to develop a new social democratic alternative.

For this Australian edition, I have added a new chapter on economic rationalism, the peculiarly Australian version of market liberalism. I discuss how this term, originally a positive self-description, became a pejorative after the recession we had to have, and how, even after repeated failures, economic rationalism remains the default ideology of the Australian policy elite.

Preface to the First Edition

The idea for this book began when I read this striking passage in Animal Spirits by George Akerlof and Robert Shiller:

The economics of the textbooks seeks to minimize as much as possible departures from pure economic motivation and from rationality. There is a good reason for doing soand each of us has spent a good portion of his life writing in this tradition. The economics of Adam Smith is well understood. Explanations in terms of small deviations from Smiths ideal system are thus clear, because they are posed within a framework that is already very well understood. But that does not mean that these small deviations from Smiths system describe how the economy actually works. Our book marks a break with this tradition. In our view, economic theory should be derived not from the minimal deviations from the system of Adam Smith but rather from the deviations that actually do occur and can be observed. (Akerlof and Shiller 2009, 45)

This passage motivated me to write about its implications for macroeconomics in the Crooked Timber blog. In comments, economist Max Sawicky, posting under the pseudonym MiracleMax, suggested that this, combined with some earlier posts on ideas refuted by the financial crisis, would make a good book. Brad DeLong of the University of California at Berkeley picked up the idea, and the next day Seth Ditchik of Princeton University Press emailed me to say he thought it was a great idea. The result is before you.

More than most books, this one has been improved by comments from others, not all of whom I can name. As I wrote draft chapters, I posted them on crookedtimber.org, and on my personal blog johnquiggin.com, then combined them in a draft on wikidot.com. I asked for comments and received, in total, several thousand, from well over a hundred different commenters, most of them pseudonymous.

I cant thank all those who commented, but I would like to mention Alice, Bert, Bianca Steele, Martin Bento, Kevin Donoghue, Kenny Easwaran, John Emerson, Freelander, Jim Harrison, JoB, P. M. Lawrence, Terje Petersen, Donald Oats, Andrew Reynolds, smiths, John Street, Uncle Milton, Robert Waldmann, Tim Worstall, and Zamfir.

I also received helpful comments from friends and colleagues, including George Akerlof, Chris Barrett, Mark Blyth, Brad DeLong, Joshua Gans, Paul Krugman, Andrew McLennan, Flavio Menezes, and Eric Rauchway. Several anonymous reviewers for Princeton University Press went above and beyond the call of duty in providing extensive and valuable comments. My wife and colleague, Nancy Wallace, read the entire text and made many helpful editorial and substantive suggestions.

Thanks also to the editorial and production team at Princeton University Press. Seth Ditchik was a marvelous and supportive editor, ably assisted by Janie Chan. Debbie Tegarden, my production editor, was unfailingly cheerful and supportive, not to mention highly efficient in turning a manuscript into a book on a very tight time frame. Other production staff including Jack Rummel and Jim Curtis gave able support. The marvelous cover design by Karl Spurzem and Dimitri Karetnikov, drawing on an idea from Seth Ditchik, speaks for itself (it says, Brraaaiiinnnssss).