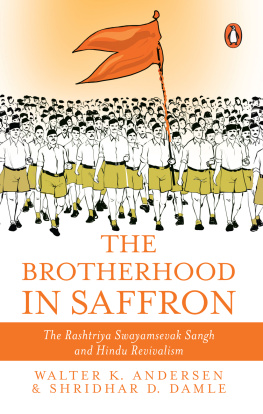

WALTER K. ANDERSEN taught comparative politics at the College of Wooster, Ohio, before joining the State Department as a politicalanalyst for South Asia.

SHRIDHAR D. DAMLE is a private consultant and has written extensively on Indian political developments.

and Dattatraya Chimanrao Damle and to Shridhar Damles late father-in-law, Shankarrao Tambe

Introduction

Every morning at sunrise groups of men in military-style khaki uniforms gather outdoors before saffron flags in all parts of India to participate in a common set of rituals, physical exercises and lessons. For one hour each day in the year, they are taught to think of themselves as a familya brotherhoodwith a mission to transform Hindu society. They are members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (hereafter referred to as the RSS), the largest and most influential organization in India committed to Hindu revivalism. The message of the daily meetings is the restoration of a sense of community among Hindus.

Organizations like the RSS which advocate the restoration of community have a salience to those who feel rootless. Indeed, the alienation and insecurity brought on by the breakdown of social, moral and political norms have become major political issues in the twentieth century, particularly in the developing countries where new economic and administrative systems have rapidly undermined institutions and moral certitudes which traditionally defined a persons social function and relationship to authority. Dislocations in primary associations which mediate between the individual and society have weakened the web of relations that provide individuals their self-identity and a sense of belonging. Social, religious and nationalist movements have proliferated to express a deeply felt need for the restoration of community.

The initial expression of this yearning for community often takes the form of religious revivalism. In South Asia, religious revivalism has taken many forms, reflecting the cultural and religious complexity of the subcontinent. Moreover, revivalist groups represented a wide spectrum of ideologies, ranging from defences of traditional orthodoxy to completely new formulations of traditional norms and practices. They mobilized communal support both to reform group behaviour and to strengthen their own groups bargaining position with the political authorities. In the process, they laid the groundwork for larger communal identities and, ultimately, nationalist movements.

In pre-Independence India, the premier nationalist organization was the Indian National Congress, an umbrella organization which accommodated a variety of interests, including the revivalists. The Congress, to retain the support of its diverse membership, adopted a consensual strategy requiring the acceptance of compromise and, by extension, the principle of territorial nationalism. However, it was not entirely successful in accommodating all groups. Many Muslim leaders, for example, felt that the westernized Hindu elite who controlled the Congress did not adequately respond to Muslim interests. Moreover, there were Hindu revivalist leaders who also believed that the interests of the Hindu community were not adequately protected by the Indian National Congress. The founder of the RSS doubted whether the Congress, which included Muslims, could bring about the desired unity of the Hindu community.

The RSS was established in 1925 as a kind of educational body whose objective was to train a group of Hindu men who, on the basis of their character-building experience in the RSS, would work to unite the Hindu community so that India could again become an independent country and a creative society. Its founder was convinced that a fundamental change in social attitudes was a necessary precondition of a revived India, and that a properly trained cadre of nationalists would be the cutting edge of that change. The two leaders of the RSS during the pre-Independence periodits founder, Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (19251940) and Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar (19401973)laid a firm foundation, supervising the training of the full-time workers who spread the organization outward from its original base in eastern Maharashtra.

Linked to the RSS in India are several affiliated organizations (referred to in the RSS literature as the family), working in politics, in social welfare, in the media and among students, labourers and Hindu religious groups. The symbiotic links between the RSS and the family are maintained by the recruitment into the affiliates of swayamsevaks (members) who have already demonstrated organizational skills in the RSS. This process guarantees a high degree of conformity to legitimate behavioural norms among the cadre in all the affiliates. It has also resulted in a high degree of loyalty to the organization on the part of the cadre. The recruitment process employed by the family of organizations around the RSS has enabled the RSS itself to remain insulated from the day-to-day affairs of the affiliates, thus protecting its self-defined role as a disinterested commentator of Indian society.

From its inception, the RSS adopted a cautious non-confrontational approach towards political authority to reduce the chances of government restrictions, but it often failed in this effort. After Independence in 1947, the RSS has on several occasions been the object of official censure, in large part because political leaders feared that it had the potential to develop into a major political force that might threaten their own power and Indias secular orientation. The RSS was banned twice (in 194849 and in 197577), and restrictions have been periodically placed on its activities. These restrictions have not weakened the RSS. Quite the contrary, they have strengthened the commitment of its members and encouraged the RSS to expand the range of its activities. Indeed, such pressures against the RSS led the organization to get involved in politics.

Nonetheless, the controversy surrounding the RSS made it (and to a certain degree its affiliates) an unacceptable partner in joint activities during much of the post-Independence period. Only since the mid-1960s has the RSS been accorded a measure of general public respect. This new respectability owes much to the participation of its political affiliate in state coalition governments during 196769, the active part played by the RSS and its family of organizations in a popular anti-corruption movement in 197375, the underground movement against restrictions on civil and political liberties during the 197577 state of Emergency, as well as to its support for the political alliance that captured power in the March 1977 national elections. Its political affiliate, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, merged into the new governing party, the Janata Party, and former Jana Sangh leaders were included in the national cabinet and served as chief ministers in several states during the twenty-seven-month period that the Janata Party remained in power. Never before had the RSS worked so closely with such a broad range of groups, many of which had previously demanded restrictions on its activities. As a result, mutual suspicions were significantly diminished, though by no means eliminated.