Table of Contents

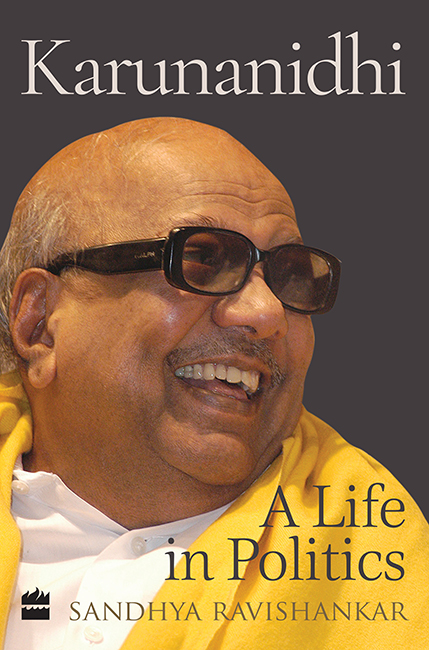

KARUNANIDHI

A Life in Politics

SANDHYA RAVISHANKAR

The first is for the first I loved.

To the leprechaun lady with shining green lanterns for eyes,

too big nose, skin of over-ripe mangoes,

who smelt always of Yardley rose talcum powder,

and who forgave and loved unconditionally until the end.

Beloved grandmother Jaka Avva,

I know you would have been the proudest.

Contents

B iography exists in different epistemological spaces. From being regarded by historians as something of a stepchild and the stuff of academic whimsy, the relevance of biographical writing to an analytic understanding of our past is much better accepted today. As a form of writing, biographies are not always contained by explanations of their subjects actions in the context of the prevailing social or political environment. Insofar as they explain the motives of people in an individualistic manner, biography is a form of psychology. Finally, as narratives, biographies are, particularly when written well, a form of creative non-fiction. They allow for the freedom to the select the stories the biographer wants to relate or highlight and provide the licence for the biographer to set the tone, the pace and the pitch in the telling.

Inevitably perhaps, Sandhya Ravishankars biography inhabits all the three spaces. Her book, which follows an unusual structure, is cleaved in two halves. The first is a largely linear account of Karunanidhis life, beginning with his birth, tracking his political rise, and his years as Tamil Nadus chief minister. The second half has a thematic quality, dwelling on topics such as Karunanidhis complex relationship with his supporter-turned-political rival MGR subjects that the author has apparently chosen because of the interest they hold and the light they throw on Tamil Nadus politics.

The other distinguishing feature in the structure of the book is framed around a series of incidents or events, some disparate, many interconnected. Interspersed with quotes, this is very much a journalists work one in which it is possible to read sections of the book as if they were separate stories about Karunanidhis long and event-filled life. It is a reminder that while human lives are a linear continuum, the stories distilled from them are the ones we believe make up their very essence.

Mukund Padmanabhan

Editor, The Hindu

April 2018

W e hunkered down every time a vehicle passed by. Sitting inside a car on a humid September afternoon in Chennai, even with the windows rolled down, was stifling. The clock ticked ever so slowly towards 4 p.m.

My colleague Satish Kumar and I had arrived at CIT Colony in central Chennai at 2.30 p.m. itself. We were employed with the young, energetic news channel CNN-IBN at the time he, a video journalist, and I, a cub reporter, in my first reporting job.

The pressure had mounted by September 2007 from our headquarters in Delhi. My boss and then bureau chief had gone to London on a three-month Chevening scholarship, leaving me to handle the explosive political situation. I had no contacts, except for a few well-meaning senior journalists who did not hesitate to give me numbers. Perhaps they felt sorry for me. Dravidian politics can be daunting even for the most experienced hand. Luckily, I had the brashness of youth on my side. Worse, I was smarting from a dressing down.

The chief minister of Tamil Nadu at the time was the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagams (DMK) M. Karunanidhi, a blessing for reporters starting their careers. Press conferences were regular and sometimes held even twice a day at the Secretariat in the afternoon and at Anna Arivalayam, the party headquarters, in the evening. There was no dearth of news.

And then the Sethusamudram project hit the headlines. Tamil Nadu and Karunanidhi were hogging the limelight. As Hindu outfits howled over the project, demanding an alternative route to the proposed shipping canal in the strip of sea between Sri Lanka and India, the atheist DMK, in alliance with the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) at the Centre, stood firm. Then Janata Party chief Subramanian Swamy, the Hindu Munnanis Ramagopalan, and others took the project to court. Their argument was that the proposed alignment for the project would mean destroying the Ramar Sethu Adams Bridge the mythical bridge built by an army of monkeys for Lord Rama to wage war with Lanka and bring home his abducted wife Seetha. This, they argued, would hurt the sentiments of Hindus.

Karunanidhi was undeterred. He would say that Rama was a lie and a drunkard. More frothing. He would refer to the Ramar Sethu as Adams Bridge, pooh-poohing mythology and Hindu religious sentiments. Froth boiled over. All to no avail.

Ally Congress, worried that the Sethusamudram issue would hurt Hindu sentiments elsewhere in the country, began to back off, adopting a pacifist tone. Karunanidhi only became more belligerent, upping the pressure on the Centre to implement the project. A bandh call was given by all parties in Tamil Nadu in late September 2007 to demand the immediate implementation of the project. And then the Supreme Court termed the planned 1 October bandh illegal.

When CNN-IBNs Supreme Court correspondent Ashok Bagriya conveyed the developments on email, I was excited. Here was a chance to redeem myself in the eyes of my boss Radhakrishnan Nair in Delhi. The wounds of a screaming the week before were still fresh in my sensitive mind.

At a regular press briefing in the chief ministers chambers in the Secretariat the previous week, a popular English news channels Chennai correspondent had played a dirty game. While all Tamil channels had placed their microphones on the chief ministers table, this correspondent kept hers at a slightly elevated level. Their video journalist framed it in such a way as to seem as if only their channel was present at what was in fact a press conference. The channel thus aired as Exclusive a regular press briefing by the chief minister on the Sethusamudram ruckus.

Radhakrishnan Nair was quick to call and yell. But sir was all I was able to get in edgeways. I was not given a chance to explain. I dont know how you are going to do it but get me an exclusive interview with him immediately, he said and hung up, leaving me furious at the injustice of it all.

Armed with Bagriyas information about the Supreme Court terming the bandh illegal, I called the chief ministers private secretary. There were two of them Marudhanayagam was ill-tempered and prone to be rude to young reporters. Shanmuganathan was even worse. I took a chance and called the latter.

Sir, the Supreme Court has termed the bandh illegal just now and stated that it will not be allowed, I told him. Please tell Ayya (respectful term in Tamil for an elder male) I would like to know what he says, I pleaded. Shanmuganathan was almost as powerful as Karunanidhi at the time.

Appadiya, he said. Is that so? Irunga. Wait. I strained to listen to the whispers wafting over the phone as Shanmuganathan conveyed the message to the chief minister.

Oru nimisham, Ayya pesanumaam, he said. One minute, Ayya wants to speak. Before I could recover from the shock came the all-too-familiar voice rasping over the phone. Ahn, enna sonnaanga? asked Karunanidhi. Yes, what did they say?