Dark Bargain

Dark Bargain

SLAVERY, PROFITS,

AND THE STRUGGLE

FOR THE CONSTITUTION

LAWRENCE GOLDSTONE

Copyright 2005 by Lawrence Goldstone

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

Published by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrmck Publishers

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

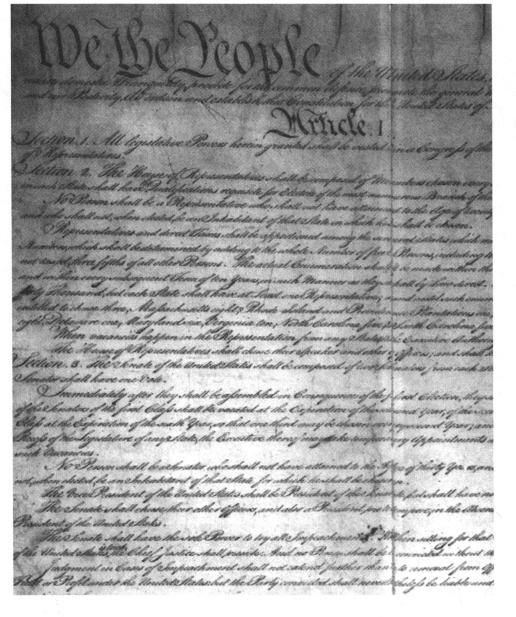

Art Credits

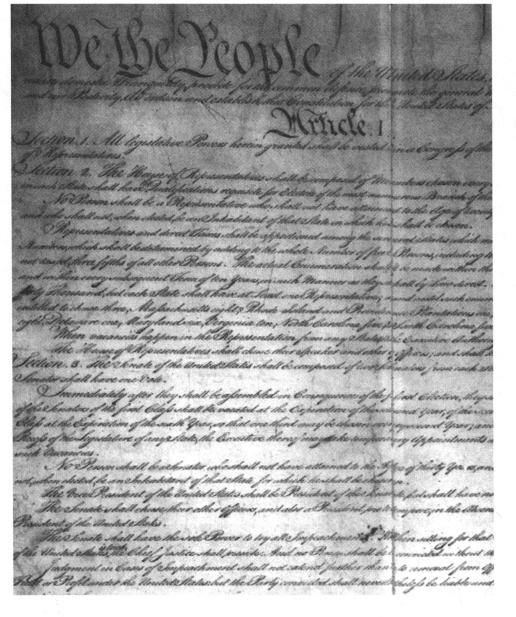

Frontispiece: National Archives. Library of Congress.

Independence National Historic Park.

New York Public Library.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as follows:

Goldstone, Lawrence, 1947

Dark bargain : slavery, profits, and the stuggle for the Constitution / Lawrence Goldstone.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. United States. Constitutional Convention (1787)History. 2. Constitutional historyUnited States. 3. SlaveryLaw and legislationUnited StatesHistory. 4- United StatesPolitics and governmental783-1789. I. Title.

KF4510.G65 2005

342.73202'9dc22

2005042315

First published in the United States in 2005 by Walker & Company

This paperback edition published in 2006

eISBN: 978-0-802-71836-5

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Book design by Maura Fadden Rosenthal/Mspace

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

For Nancy and Emily

CONTENTS

Dark Bargain

Fulcrum

O n the morning of Thursday, January 17,1788, General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney rose to address his colleagues in the South Carolina General Assembly. One of the state's most distinguished and respected citizens, famed for his exploits in both peace and war, the general was a fourth-generation Carolinian who could trace his lineage to a vassal of William the Conqueror.

Born in 1746, son of a future chief justice of the South Carolina courts, Pinckney had been sent to Oxford to study law, where he read with the great legal theorist William Blackstone. He had returned to set up his own practice, but soon joined the struggle for independence as an aide-de-camp to General Washington. Pinckney won quick promotion and in 1780 was one of the officers charged with resisting the British siege at Charleston. Even in the face of overwhelming force, he had advocated fighting on, only agreeing to surrender after intense persuasion by his fellow officers. As a result, he spent the next year as a British prisoner of war. When his captors tried to persuade him to change sides, Pinckney said, "If I had a vein that did not beat with the love of my Country, I myself would open it. If I had a drop of blood that could flow dishonourable, I myself would let it out."

For all his lineage and fame, however, on that January morning in 1788, General Pinckney, described as "an indifferent Orator," faced possibly the greatest challenge of his life. The debate he was about to join, which had begun the previous day and would continue for two more, was crucial not only to the future of his state, but quite possibly would determine the very survival of the fledgling nation he had battled for and been imprisoned to secure. The subject was whether to call a convention to ratify the proposed new Constitution.

The Constitution had been drafted the previous summer in Philadelphia, fifty-five men from twelve states participating in often rancorous debate on how best to rescue the United States from the obviously inadequate Articles of Confederation. had been one of the four delegates chosen to represent South Carolina.

According to the plan that had emerged from the convention, nine states would have to ratify the new Constitution if the Articles were to be replaced. Fulcrum By the time the South Carolina legislature took up the question of whether to authorize a ratifying convention, five states had already approved the document and conventions to take up the question were scheduled in a number of others. Still, adoption was very much in doubt. Intense opposition existed in New York, and ratification was far from certain in Massachusetts. Virginia, perhaps the most important state in the Union in terms of wealth and strategic location, would not even meet to consider the new Constitution for months, and sentiment in the Old Dominion was not encouraging. Virginia's governor, Patrick Henry, a rabid opponent of ratification, was already famous for his refusal to even attend the convention. "I smelt a rat," he had noted with typical understatement. If the South Carolina legislature declined to call a ratifying convention, it could well start a cascade of rejection.

Many South Carolinians were leery of ceding local prerogative to a central government, particularly one that might be dominated by the North. Under the Articles, each state voted as a unit, and at least nine votes were required to pass even the most basic legislation. As a result, the five southern states effectively maintained veto power over any measure that might be rammed through by the eight states to the north. Under the voting rules of the new Constitution, that blanket veto would be lost. Fear that tyranny and despotism were therefore just around the corner had to be overcome if South Carolina were to approve the new Constitution.

Heading the opposition was a figure of equal stature, Rawlms Lowndes, who had been South Carolina's second president.

"It has been said that this new government was to be considered as an experiment," Lowndes had said.

Lowndes's proclamation had ended a day of long and grueling debate. It had begun with Charles Pinckney, the general's cousin, giving a lengthy description of the plan that had emerged the previous September. The younger Pinckney, headstrong and brillianthe had lied about his age so as to appear to be the youngest delegate in Philadelphiahad spoken for most of the morning. When he finally concluded his remarks, the delegates had eschewed a paragraph-by-paragraph reading of the new Constitution, but had instead launched immediately into a debate on the aspect of the plan that they found most frightening. Since, as one of the representatives put it, the president of the United States "was not likely ever to be chosen from South Carolina or Georgia" ( a prediction that remained accurate for almost two centuries), executive power seemed to be of the most concern. Curiously, of all the powers of the presidency, it was the authority to negotiate treaties on which the delegates focused.

Almost the entire afternoon was spent discussing the treaty power, both in terms of its being binding on individual states and the need for a two-thirds vote in the Senate to ratify. Still, there was a surprising lack of specifics as to just what sort of treaties the South Carolinians found most objectionable. Instead, the debate was conducted on a philosophical plane, filled with comparisons to other governmentsEngland and France, especiallyand the theoretical dangers of treaty making and the potential for despotism. Then, just before the delegates were to adjourn for the day, Lowndes rose to speak, and the meaning of the previous debates became clear.