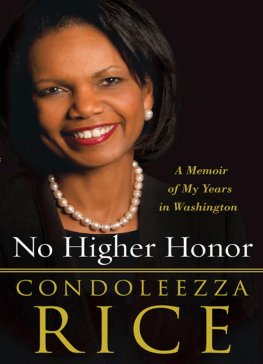

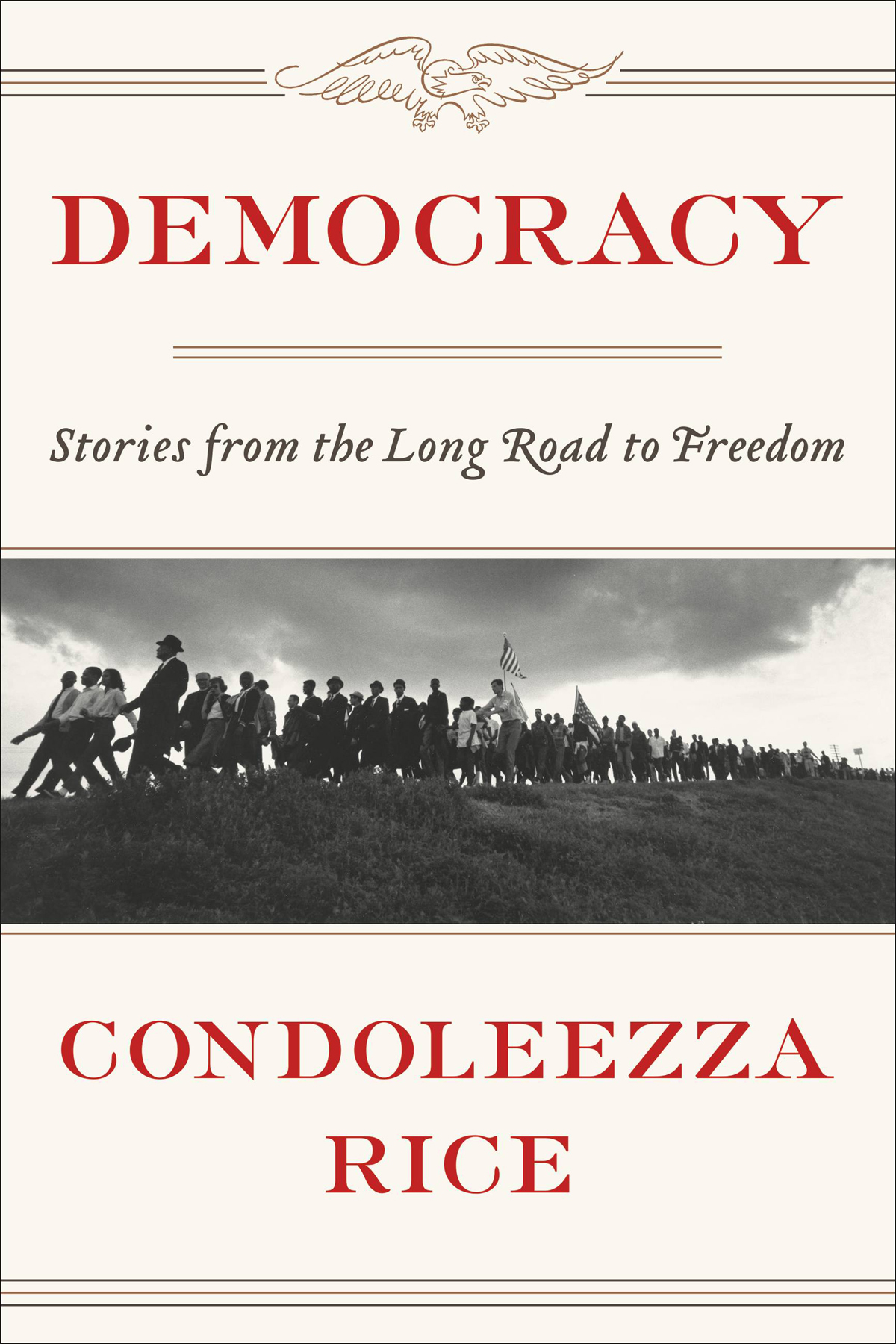

I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come. But I can only rest for a moment, for with freedom comes responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not ended.

L isa, Christann, and I had been in Moscow for too long and we were happy to be headed home. Suddenly we were landing in Warsaw, an unscheduled stop. Leave all your possessions and get off the plane, we were told over the PA system. We sat for hours in the airport, terrified that we were being detained for some unspecified crime. It was 1979 and we were three American girls in a communist country. After what seemed like a lifetime, we were told to get back on the plane. It took off, and when we landed in Paristhe site of our connecting flight to the United States and a city safely within the Westwe cried.

Ten years later, in July 1989, I visited Poland again, this time with President George H. W. Bush. Mikhail Gorbachev was general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party and he was rewriting the rulebook for Eastern Europe, loosening the constraints that had sustained Moscows power. Poland was a very different place now. The first night of the visit, we were in Warsaw, guests of a dying communist party. The lights went out during the state dinnera perfect metaphor for the regimes coming demise.

The next day we went to Gdask, the home of Solidarity and its founder, Lech Wasa. This was the new Poland, experiencing dramatic and sudden change. We entered the town square where one hundred thousand Polish workers had gathered. They were waving American flags and shouting, Bush, Bush, Bush Freedom, Freedom, Freedom.

I turned to my colleague Robert Blackwill of the National Security Council staff and said, This is not exactly what Karl Marx meant when he said, Workers of the world unite. But, indeed, they had nothing to lose but their chains. Two months later, the Polish Communist Party gave way to a Solidarity-led government. It happened with dizzying speed.

The revolutions that began that summer in Poland and followed in most of Eastern Europe proceeded with minimal bloodshed and maximum support among the people. There were exceptions. In Romania, power had to be wrested by force from Nicolae Ceauescu; he resisted and tried to flee but was ultimately executed at the hands of revolutionaries. In the Balkans the breakup of Yugoslavia unleashed ethnic tensions and violence, the legacy of which can still be felt today. Russias own democratic transition at first appeared promising but ultimately failed entirely, replaced today by Vladimir Putins autocratic rule and expansionist foreign policy. Yet, with these important exceptions, the end of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union spawned several consolidated democracies and the region is largely peaceful.

The climb toward freedom in the broader Middle East and North Africa has been a far rockier story. Whether in still-unstable Afghanistan and Iraq, where the United States and our allies were midwives to the first freely elected governments; in Syria, which descended into civil war; or in Egypt, where the awakening of Tahrir Square turned into the thermidor of a military coup, there is turmoil, violence, and uncertainty. Turkey, perched between Europe and the Muslim world, has recently experienced a military coup attempt and subsequent crackdown. There and across the Middle East, citizens and their governments struggle to find the right marriage of religious conviction and personal freedom. The region is in a maelstrom.

I have been fortunate enough to be an eyewitness to these two great revolts against oppressive rule: the end of the Soviet Union at the close of the twentieth century and freedoms awakening in the Middle East at the beginning of the twenty-first. I have watched as people in Africa, Asia, and Latin America have insisted on freedomperhaps with less drama than in the Middle East, but with no less passion. And in fact, as a child, I was a part of another great awakening: the second founding of America, as the civil rights movement unfolded in my hometown of Birmingham, Alabama, and finally expanded the meaning of We the people to encompass people like me.

These experiences have taught me that there is no more thrilling moment than when people finally seize their rights and their liberty. That moment is necessary, right, and inevitable. It is also terrifying and disruptive and chaotic. And what follows it is hardreally, really hard.