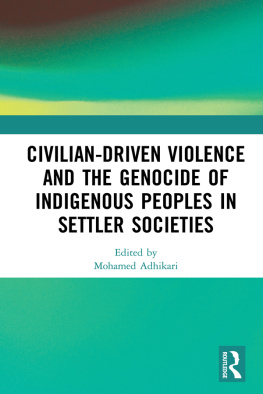

The Civilisation of Port Phillip

The Civilisation of Port Phillip

Settler ideology, violence, and rhetorical possession

Thomas James Rogers

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston St, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2018

Text Thomas James Rogers, 2018

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2018

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

The views expressed in this book are the authors own, and do not represent the views of any institution.

A shortened version of has been published as Friendly and hostile Aboriginal clans: The search for Gellibrand and Hesse, History Australia, vol. 13, no. 2, 2016, pp. 27585.

An expanded version of a section of has been as The killing of Charles Franks and the obliteration of Port Phillips convicts, Victorian Historical Journal, issue 285, vol. 87, no. 1, 2016, pp. 11733.

Index compiled by Jo Kim and the author

Text design by Phil Campbell

Cover design by Phil Campbell

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by OPUS Group

9780522870602 (paperback)

9780522872385 (hardback)

9780522870619 (ebook)

For Jo

Contents

Acknowledgements

First of all, I thank my partner, Jo Kim. She gave me constant support and encouragement throughout my PhD candidature, which led to the thesis that became the basis of this book. Without her warm encouragement and exacting critique, not to mention her role as the breadwinner of the house during that time, this book would not have been written.

My two thesis supervisors were generous in their time, ideas, and suggestions. My primary supervisor, Andrew May, enjoined me to return to the archive whenever I was in doubt about the project of history writing. I thank Andy for ensuring that my candidature went beyond simply writing a dissertation. My secondary supervisor, Stuart Macintyre, also pushed me beyond the thesis. His deep knowledge of Australian and British historiography made the final work a deeper one than it otherwise would have been. The two examiners of the thesis, Kirsten McKenzie and Maria Nugent, provided detailed feedback. I really appreciate the care they both took in marking. Their comments helped me to improve the book.

Anyone who has taught knows that teaching is actually a process of learning, which is partly why it is so rewarding. I thank the students in my many and varied history classes over the years for their enthusiasm and ideas. Thanks also to everyone who shared their teaching knowledge with me: at the University of Melbourne, Richard Pennell, James Bradley, Richard Trembath, Trevor Burnard, Sara Maroske, Kathryn Smithies, Joy Damousi, Jordy Silverstein, Mary Tomsic, and Meighen Katz; Nell Musgrove and Naomi Wolfe at Australian Catholic University; and Sergio Fabris, Vice-Principal of St Hildas College. I found a community of supportive historians at the University of Melbourne, and I appreciated the encouragement and support of Sean Scalmer, Steve Welch, David Goodman, Antonia Finnane, Elizabeth Malcolm, Kate Darian-Smith, and Frederik Vervaet.

My postgraduate cohort was a resource for discussions about teaching, academic endeavour, history, and life. I was fortunate to study alongside Mark Pendleton, Erik Ropers, Julie Davies, Stephen Ireland, Esther McGill, Michael Pickering, Emily Fitzgerald, Keir Wotherspoon, Alyssa Trometter, Alexandra Dellios, Bron Lowe, Pete Minard, Alex Chorowicz, Stephen Bain, Andr Brett, Susan Reidy, Jess Melvin, Shane Tas, Jason Ng, Shan Windscript, and many others.

Penny Edmonds was a supportive colleague even before she was assigned my article as part of the Australian Historical Association/Copyright Agency Limited mentoring program at Wollongong in 2013, and her thoughtful suggestions are very much appreciated. I also thank the AHA/CAL for selecting my work to support in that wayits a very good program, and I hope it can be continued and expanded.

The doctoral thesis on which this book is based won the 2014 Dennis-Wettenhall Prize, awarded annually to the best thesis in Australian history submitted to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne. The prize money went towards the costs of publication, and I thank Roland Wettenhall for his familys generosity.

I had a succession of excellent history teachers. Doug McKenzie, my US history teacher at Middletown High School South in New Jersey, had an abrasively brilliant style of teaching that showed me the importance of ideas to actions. Back home in Melbourne, Angela Hey managed to captivate teenage minds, bringing the Italian Renaissance to life. At university, I was taught by Ron Ridley, whose elephant-like memory and flair for teaching both astounded and inspired me.

I am grateful to the staff of the Baillieu Library at the University of Melbourne, State Library of Victoria, Public Records Office, and Royal Historical Society of Victoria.

Finally, I thank my family, Alison, Margot, Mum and Dad, for their support throughout. My parents, David and Judy, endured a childhood of why questions and have always supported my education.

Tom Rogers

Canberra, 2018

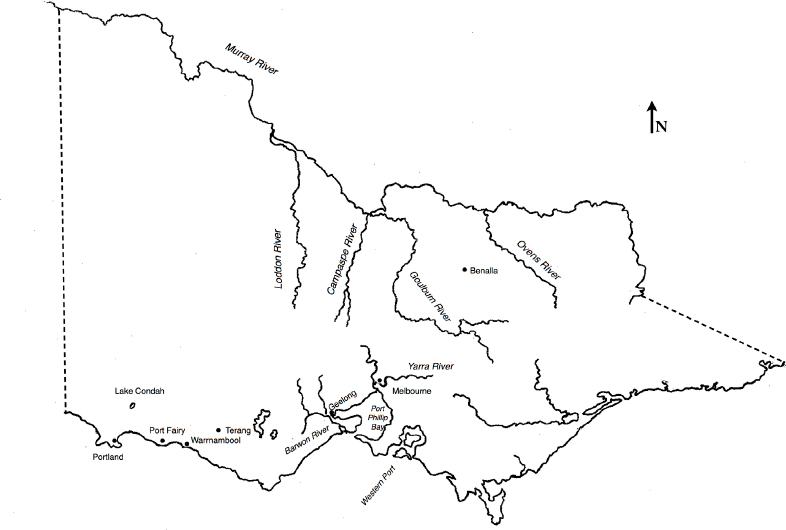

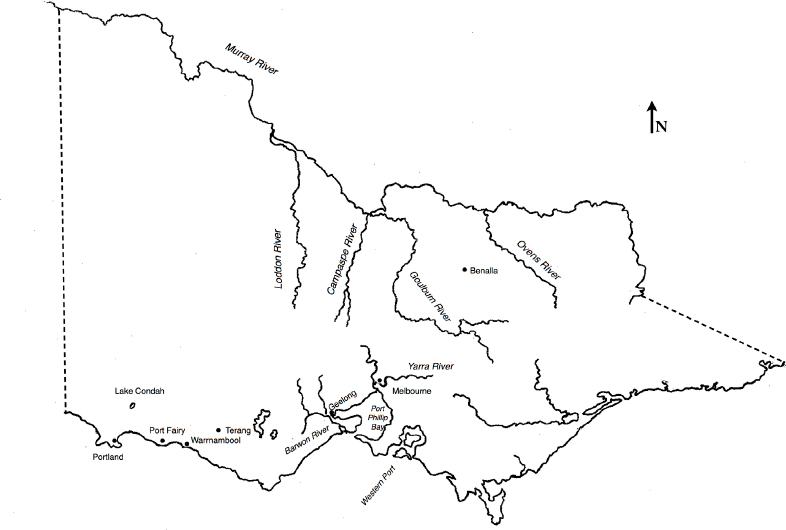

Port Phillip District, map reproduced by hand by the author, following A.G.L. Shaw, A History of the Port Phillip District (Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press, 1996), x-xi.

Introduction

Cowardice and savagery disturbed Governor George Gipps when he considered the best way to oversee the taking of civilisation to the troubled southern plains of his colony of New South Wales. Describing a recent massacre of Britons by Aboriginal warriors near present-day Benalla, in 1838 he wrote to his superior in London, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies Lord Glenelg: These men (who were chiefly convicts) did not defend themselves, but ran at the first appearance of their assailants, though, as there were 15 of them with firearms in their hands, they ought to have beaten off any numbers however great of naked savages.

The incident on the Broken River came to be known as the Faithfull massacre after the free settlers for whom the servants worked, the brothers George and William Pitt Faithfull. In this early incident and its aftermath, we can see some of the most important themes of early Port Phillip history: the notions of aggressive savages and cowardly convicts, the idea of the spread of British civilisation, and the gap between those on the frontier and the colonial authorities in Sydney, London, and Melbourne.

The Port Phillip District in 1838 was part of New South Wales, and was to remain so until Separation, which came into effect in 1851. In this book I use the term Port Phillip to refer to the land

Next page