Introduction

Creeping Coup

In the years before the Nazi invasion, as fascism pulled activists from the ranks of the left, Popular Front leader L on Blum spoke of a contagion gripping France. More recently, warnings of a creeping fascism have returned.

If we consider the lefts embrace of equality as its defining characteristic, fascism remains decisively on the right.

Perhaps the most important strategy of fascism is what scholar Stephen D. Shenfield calls a gradual or creeping coup, accomplished by means of the steady penetration of state and social structures and the accumulation of military and economic potential. Similarly, the increasing power of the radical rights populist parties in Europe indicates a drift of socialists, liberals, and conservatives toward a counterhegemonic alternative. Many of these parties, like the Brothers of Italy, the French Front National, the Austrian Freedom Party, the Ukrainian Svoboda, the Sweden Democrats, and the Flemish Vlaams Belang have clear roots in the fascist movement. Yet the more power and influence they gain, the less they seem to cling to the hard core of their original ultranationalist ideology, focusing instead on pragmatic policy issues and the complex geopolitical questions pertaining to the European Union and Russia. Concern remains that, on achieving singular power, these parties would revert to fascist positions or at least provide enhanced material support to fascist groups.

The relationship between the fascist movement and the populist radical right, though at times supportive, is fundamentally dynamic, divided, and complex. Openly fascist groups tend to be much smaller, and they tend to argue for a national revolution more antiparliamentary than their radical-right counterparts. Hardcore fascism tends to be far more mass-based and revolutionary, radically traditionalist and elitist than most radical-right configurations. Nevertheless, fascist ideology is not always transparent, and left-right crossover along with misleading rhetoric surrounding the State of Israel, Islam, and multiculturalism tends to obscure the extent of racism. This space of relative autonomy between the radical, right-wing populist parties and smaller, dedicated fascist groups is important. It brings a conservative appeal to the radical right, who are also able to attract left-leaning members of the public with social welfare promises. Meanwhile, it enables smaller groups to attract members of the public who desire a more anti-institutional transformationeven if those smaller groups often overlap considerably with larger, radical and conventional right groups through unofficial or mediated channels.

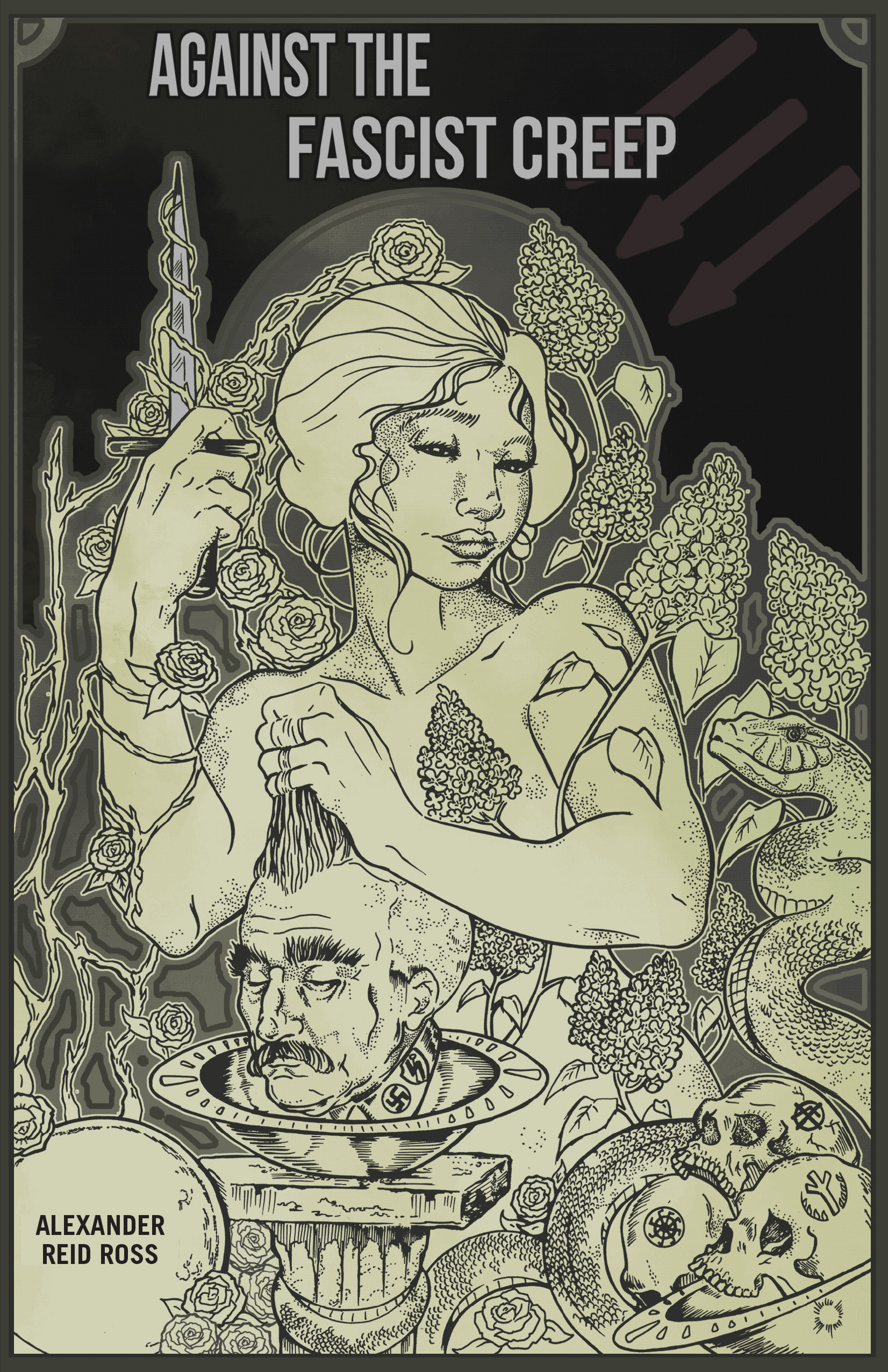

The fascist creep, as I am using the term in this text, refers to the porous borders between fascism and the radical right, through which fascism is able to creep into mainstream discourse. However, the fascist creep is also a double-edged term, because it refers more specifically to the crossover space between right and left that engenders fascism in the first place. Hence, fascism creeps in two ways: (1) it draws left-wing notions of solidarity and liberation into ultranationalist, right-wing ideology; and (2), at least in its early stages, fascists often utilize broad front strategies, proposing a mass-based, nationalist platform to gain access to mainstream political audiences and key administrative positions. Against the Fascist Creep will reveal how these processes of fascism have worked in the past and how they manifest today, as well as ways in which radical movements have organized to stop them in their tracks.

So What is Fascism?

Is fascism a kind of attitude, personality, or a manifestation of unconscious drives based on patriarchal repression? Is it simply a mode of political formation present in Italy between 1919 and 1945?

More recent analysts like George Mosse and Stanley Payne ascribe a checklist with boxes for antiliberal, anticonservative, anti-Marxist, sacralization of politics, leader cult, single party, integral corporatism, media censorship, organic theory of the state, ultranationalism, focus on the youth, and extreme political violence. That means that fascism is an ideology that draws on old, ancient, and even arcane myths of racial, cultural, ethnic, and national origins to develop a plan for the new man.

Dissenters from the Marxist camp like David Renton favor an evolution of Leon Trotskys analysis, viewing fascism as a cross-class alliance between the petite bourgeoisie and the ruling class, which were intent on destroying the vanguard of the proletariat.

In my opinion, there is no contradiction between palingenetic ultranationalism and a cross-class alliance. Ultranationalism assumes a cross-class national community. However, fascisms syncretic form of fringe fusion takes place as a result of extreme responses to modern conditions, and it attacks only those members of the left designated as competition for political power. The leading three fascist political figures of the interwar period in France were all former leftists: a former member of the inner committee of the Communist Party, a former anarcho-syndicalist, and the leader of the neo-socialist faction of the Socialist Party (then called the French Section of the Workers International). The movement was led by a host of frustrated and powerful leftists joining with sectors of the nationalist radical right to attack liberalism.

Fascism is also mythopoetic insofar as its ideological system does not only seek to create new myths but also to create a kind of mythical reality, or an everyday life that stems from myth rather than fact. Fascists hope to produce a new kind of rationale envisioning a common destiny that can replace modern civilization. The person with authority is the one who can interpret these myths into real-world strategy through a sacralized process that defines and delimits the seen and the unseen, the thinkable and the unthinkable.

That which is most commonly encouraged through fascism is producerism, which augments working-class militancy against the owner class by focusing instead on the difference between parasites (typically Jews, speculators, technocrats, and immigrants) and the productive workers and elites of the nation. In this way, fascism can be both functionally cross class and ideologically anticlass, desiring a classless society based on a natural hierarchy of deserving elites and disciplined workers. By destroying parasites and deploying some variant of racial, national, or ethnocentric socialism, fascists promise to create an ideal state or suprastatea spiritual entity more than a modern nation-state, closer to the unitary sovereignty of the empire than political systems of messy compromises and divisions of power. This spiritual entity of the future would require the annihilation of the contaminated modern world and a return to the myths of ancestral ties of blood and soil, culture, and language that bind the community together in spite of class antagonisms.