LILLIAN ROSS (19182017) was born Lillian Rosovsky in Syracuse, New York. Raised in Brooklyn, she published her first piece of journalism, an article about a new library, in her junior high school newspaper. After graduating from Hunter College in 1939, Ross wrote for the leftist New York tabloid PM until she was hired by The New Yorker in 1945. She filed dispatches for the Talk of the Town section until her first major article, a 1949 profile of a matador from Brooklyn; she would go on to write more than five hundred pieces for the magazine. In 1966, she adopted a son, Erik, from Norway. Ross edited three collections of Talk of the Town feuilleton and published a dozen books, including one work of fiction, Vertical and Horizontal (1963); several anthologies of her journalism; and a memoir, Here But Not Here: A Love Story (1998), about her long relationship with William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker. In 1974, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. Her last piece for The New Yorker was a 2012 memoir of her friend J. D. Salinger.

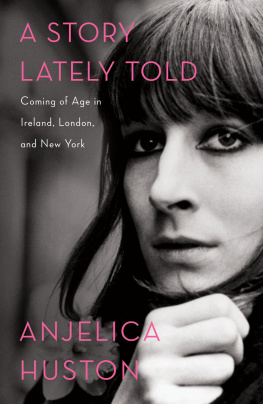

ANJELICA HUSTON is an actor, director, and writer. The daughter of John Huston, she has appeared in more than fifty films, including Prizzis Honor (1985), for which she won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. She has written two volumes of memoir, A Story Lately Told: Coming of Age in Ireland, London, and New York (2013) and Watch Me (2014).

Lillian Ross on the set of The Red Badge of Courage. Photograph by Silvia Reinhardt.

PICTURE

LILLIAN ROSS

Foreword by

ANJELICA HUSTON

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1952, 2002 by Lillian Ross

Foreword copyright 1993 by Anjelica Huston

All rights reserved.

Cover image: John Huston on the set of The Red Badge of Courage, 1950;

photograph by Ralph Crane; LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ross, Lillian, 19182017, author.

Title: Picture / by Lillian Ross.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2019] | Series: New York Review Books Classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2018024728| ISBN 9781681373157 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681373164 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Red badge of courage (Motion picture)

Classification: LCC PN1997.R383 R6 2019 | DDC 791.43/72dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018024728

ISBN 978-1-68137-316-4

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

D URING his lifetime and after his death, much has been written about my father, John Huston. The stories have abounded, often from firsthand witnesses, working partners, ex-wives, girlfriends, rivals, fellow-journeymen, and strangers. He has transcended biography on occasion and even been presented in the form of a novel. Among other things, he has been described as a hedonist, a womanizer, a mans man, a sportsman, a gambler, a practical joker, a drinker, and an adventurer. On many occasions, he has been compared to Ernest Hemingway, which I think does neither of them a great service. What seems to me the great disappointment of these somewhat superficial, often spurious comparisons, is that, somewhere in all the adjectives and descriptions, an essential point is lost. My father was all these things and more. He was an artist. It was my father as an artist that fascinated Lillian Ross. She never sought to write gossip or to go beyond a particular line that she drew for herself in his personal life.

In May of 1986, my father asked Lillian to accept the Brandeis University Creative Arts Award in New York City on his behalf, as he was recovering from eye surgery. She told the Creative Arts presenters:

Throughout his life, he has looked intently at, and continues to look at, the art, in all its forms, of other artists, from the earliest time to the present. He looks at art in the happiest of ways: with his entire being and without intellectualization. And whenever possible, in the case of living artists, he transmits to its creators, with his own Hustonian enthusiasm, his utter joy and astonishment at what he sees.

Much the same can be said of Lillian herself. They shared a boundless interest in life.

I remember flying to New York with my father in 1986. He was very ill at the time, permanently connected to an oxygen tank in order to stay alive. Journeys of this kind were always touch-and-go and the consequences life-threatening. I was worried. We arrived in New York late at night. My father was pale and exhausted. The next morning, I was awakened from a deep sleep by the telephone. It was 8 A.M. Lillian and I are off to the museums. Want to come?

I hadnt been born yet when Lillian came out to California to write Picture, her account of my fathers making of The Red Badge of Courage. After the publication of Picture, her friendship with my mother and father not only continued but flourished, until my mothers death in 1968 and my fathers in 1987. I grew up hearing about Lillian and meeting her from time to time. My parents loved and respected her, and trusted her. She was, they would say, different from other reporters.

A key to that difference is, I think, revealed in her statements about her principles in the introduction to her book Reporting. She writes:

As soon as another human being permits you to write about him, he is opening his life to you and you must be constantly aware that you have a responsibility in regard to that person. Even if that person encourages you to be careless about how you use your intimate knowledge of him or if he is indiscreet about himself or actually eager to invade his own privacy, it is up to you to use your own judgement in deciding what to write. Just because someone said it is no reason for you to use it in your writing. Your obligation to the people you write about does not end once your piece is in print. Anyone who trusts you enough to talk about himself to you is giving you a form of friendship. You are not doing him a favor by writing about him, even if he happens to be in a profession or business in which publicity of any kind is valued. If you spend weeks or months with someone, not only taking his time and energy but entering into his life, you naturally become his friend. A friend is not to be used and abandoned; the friendship established in writing about someone usually continues to grow after what has been written is published.

Lillians writing is the proof of what she says. She maintains her own integrity and she respects the integrity of her subject. She never stoops to gossip or speculation. Her powers of observation are immense.

In the country recently, my husband, Robert Graham, and I were reading Picture aloud to each other. We were laughing and having a lot of fun when suddenly I realized that reading this book was like being in the same room with my father again.

I thank Lillian for her marvelous and timeless documentaryand for this portrait of my father, with all his changing profiles, as observed by one who shared his talent for beauty, humor, simplicity, and truth.