Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

Without the will required to see that which is obscured, we will continue to produce and reproduce human beings and social relationships rooted in inequality and captivity.

CHARLES MILLS, The Racial Contract

INTRODUCTION

THE HEROIN HIGHWAY

AT ANY TIME OF DAY, on any day of the year, you can see cars zooming down Chicagos Eisenhower Expressway. The bulk of drivers head to downtown jobs in the morning, rushing to desks with coffee in hand. In the evening, they drive out into the sunset, a pink and orange sky that appears for twenty or so fleeting minutes, a temporary horizon equally accessible to all. Those drivers head back to subdivisions and cul-de-sac homes, communities that might have made President Eisenhower smile. Going the opposite way, city dwellers head out to suburban jobs in the morning. They make the reverse commute at night, many of them heading back to friends, partners, and kids of their own.

Each day the expressway is filled with cautious motorists and careless lane switchers focused on the views directly in front of them. Windshields discipline their gaze and frame their focus. Through their radios, the world speaks many tongues: Talk shows and soft rock. R&B and throwback hip-hop. Classical music and country. Each car its own listening booth en route to its destination. While each vehicle makes its own journey, the larger patterns are cleara predictable flow of traffic, rising to intense peaks on weekday mornings and evenings. The flow bridges downtown Chicago, the regions western suburbs, and the half-dozen neighborhoods that stand in between. Drivers within this traffic all share the same asphalt trade line. For the length of their commute, they are bound by the same lanes, speed limit, and rules of the road. But each and every day, they enter and exit diverging worlds, where the rules differ wildly.

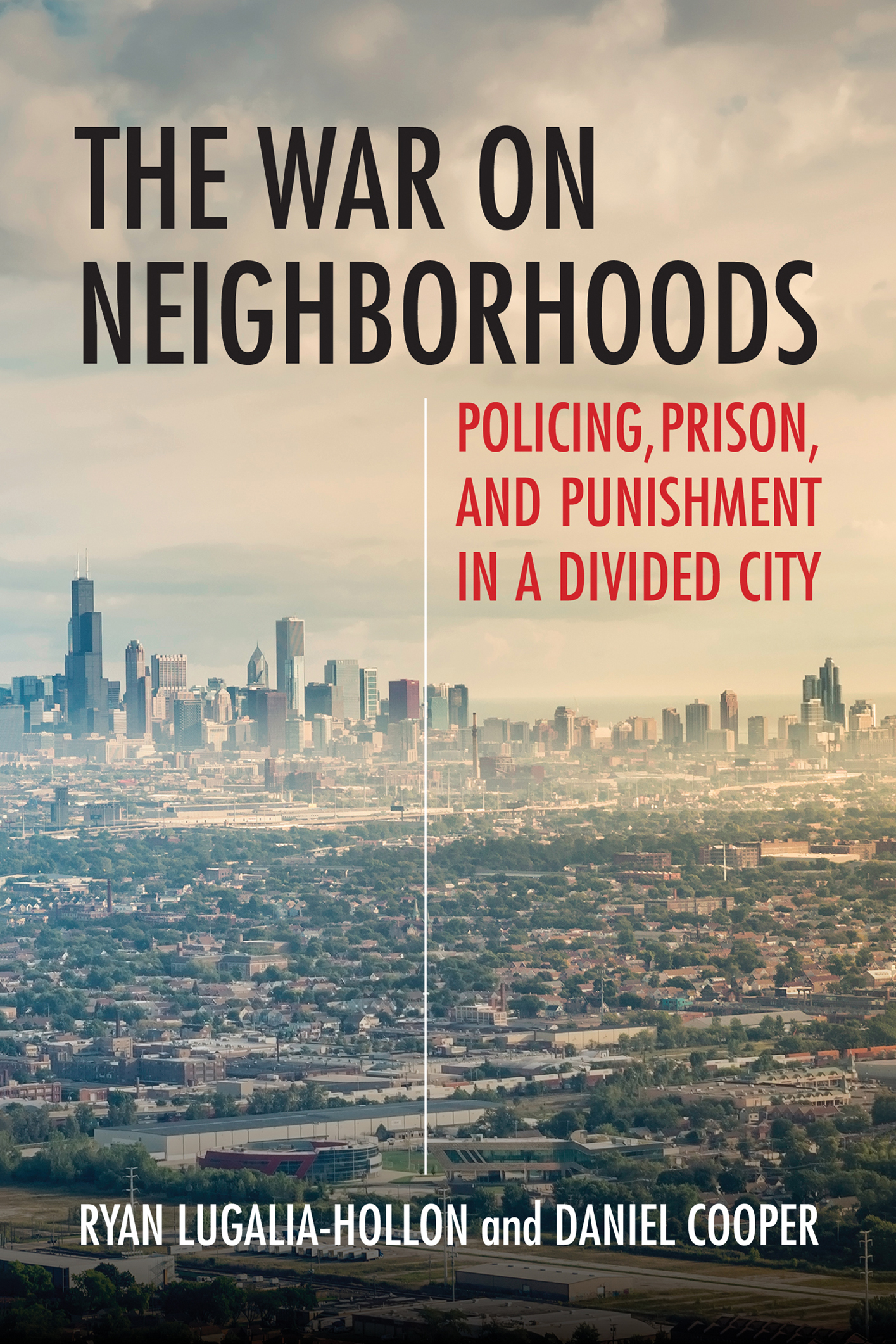

Every few off-ramps, a new world begins. Depending on where you get off, the housing stock changes: from the high-rise condos at the heart of the city, to brick homes near Little Italy, to West Side graystones, to the charming mini-mansions of inner-ring suburbs, and, finally, the sprawling newer construction deep in suburbia. Employment levels vary dramatically. Chicago, where race and geography are commonly linked, has one of the largest racial employment gaps in the county. The employment rate for whites is about 73 percent among twenty- to twenty-four-year-olds, compared to 47 percent for blacks in the same age range.

The Eisenhower Expressway begins in the citys center. Downtown Chicago is home to skyscrapers, theaters, hidden restaurants, and universities. It is also home to city halls fifth floor, where Chicagos mayors have chosen, with surprisingly few exceptions, to pour their greatest resources into a vibrant central business district and a robust police force. These mayors, like the city councils theyve controlled, have labored under the delusion that a rising downtown might lift all boats and that neighborhoods left behind could simply be policed. Meanwhile, the undercurrents of violence and addiction have never ceased, drowning thousands and thousands of Chicagoans each year with waves that constantly pound on much of the citys West and South Sides. These same mayors have struggled to keep reporters at bay when these waves are detected by national media outlets, when outbreaks in shootings confirm, yet again, the limits of their theories on how to make a city great.

Head west from downtown and youll reach the Morgan Street exit, where youll find the University of Illinois at Chicago, a large state school. The campus, composed of concrete buildings, is organized around a large riot-proof tower, built in an era in which fear of racial unrest was translated into defensive architectural design. Erected roughly a decade after the expressway was opened, the tower hovers quietly, looking over the daily traffic, a reminder of a time when vast racial inequality was not so well disguised. The remnants of Greek Town and Little Italy are near the campus, each with its own ethnic restaurants and small stores, carryovers from a time before the university and the expressway displaced tens of thousands of white immigrant families.

Drive farther away from downtown and you will pass through the Near West Side, North and South Lawndale, East and West Garfield Park. If you exit at Central Avenue, you will be in Austin, the most western part of Chicagos West Side. This area is the focus of our story. Like much of the West Side, Austins economic bottom started to fall out after World War II, with the onslaught of deindustrialization. Once a mecca for the production of goods as diverse as candy and telephones, boarded-up factories are now strewn across its major thoroughfares.

While billions in tax subsidies have gone into the development of Chicagos downtown from the 1980s through the present, the West Side economy has been heavily neglected. Businesses still line Austins commercial corridors, but shoppers are fewer and farther between, and prices must be kept low enough to stay relevant in a neighborhood where living-wage jobs are all but an urban legend. Disposable income is rare. Often, unbudgeted purchases cannot be afforded, without risking the rent, diapers, or groceries. The parks are gorgeous and abundant, but the programs and sports leagues that should fill them up are too few. Meanwhile, imprisonment has been used to obscure the deeper needs of the neighborhood: the need for jobs, more stable housing, well-resourced schools, and a higher quality of life. Though it has failed to uproot gang violence or drug sales, the criminal justice system has been the dominant approach to neighborhood governance since the 1980s.

Riding westward, the next exit leads to Oak Park, the first suburb past Chicagos western city limit and a common congestion point for traffic. The census reads very differently here, as does the institutional landscape and the approach to governance. Oak Park is a land of great schools and vibrant businesses. On lunch breaks, evenings, weekends, or anytime in their retirement, Oak Parkers can choose from a wealth of bars, ice cream shops, and restaurants. Many of them have the income available to do so regularly, a benefit accumulated from years of great-paying jobs, from family wealth passed down the generational bloodline, from investment strategies now paying dividends, or from a little bit of all three. Here, double-income households are the norm. The median household income of $80,196 is more than double that of neighboring Austins $33,800. Its buildings are deemed beautiful, and lovers of architecture pass through regularly to see the Prairie houses designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, a Midwestern point of pride. Here, imprisonment is a rare occurrence, with the criminal justice system playing a relatively minor role in community life.

The impacts of racism on these diverging landscapes is often hard to perceive. From the expressway, drivers cannot see the legislative histories, tax codes, and public-spending patterns that shape the terrain. There are no road signs explaining that redlining prevented banks from investing in West Side neighborhoods in the 1960s and 70s, using artificial geographical lines to refuse loans to people because of their race and class. Nor are there markers of the inverse strategy that targeted households in these areas for subprime loans in the 2000s. Drivers cannot see the white flight that persisted throughout the closing decades of the twentieth century, the ways that fear of black neighbors helped to drive the fast sales of homes and that real estate agents exploited the atmosphere for personal profit. They cannot see how the residents in some communities are much more likely to be punished, to be removed from their homes, taken away from families and neighbors for years at a time.