SOCIAL

BUTTERFLIES

First published in Great Britain in 2019

by Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael Sanders and Susannah Hume 2019

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-957-8 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78929-117-9 in trade paperback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-978-3 in ebook format

www.mombooks.com

Contents

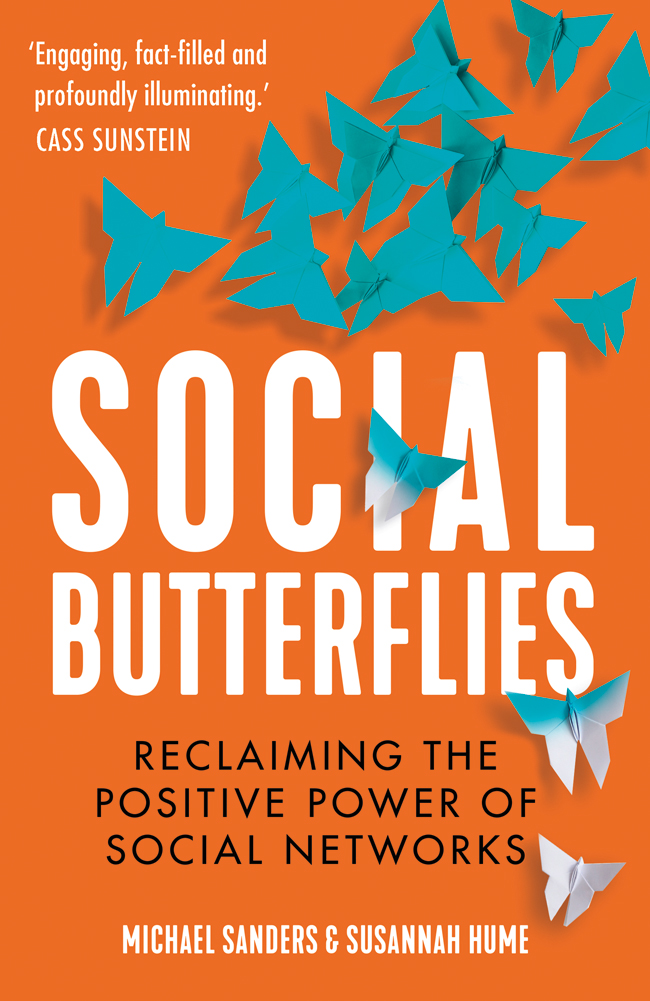

W E ARE ALL social animals. Our social instincts and propensity to form and sustain groups with shared loyalties, motives and culture are in many ways the story of humanity. Without the social part of ourselves there could be no societies. Without the ability to work together we couldnt develop organized and structured agriculture. Without agriculture we couldnt have moved into towns; and without the capacity to get along and forge shared identities we couldnt have survived for long in those towns, let alone in the complex, interconnected communities and structures we now inhabit.

In the twenty-first century, more than ever before, we behave as social butterflies. Were able to move between social categories and groups at will, and we now have unprecedented and numerous means to communicate with each other. But were also butterflies in another way. Chaos theory suggests that the changing of something very small the flap of a butterflys wings can have a disproportionate influence on the world. As social butterflies, we influence others in ways that we dont always realize and we, in turn, are unwittingly influenced by others. These influences are, at least in part, responsible for many of the wonderful things in the world: culture, sport, the formation and cementing of friendships, and our charitable behaviours.

But our instinct to get along with others can also lead us in less positive directions. In September 2007, in one of the earliest manifestations of what would become the 20078 Global Financial Crisis, the British bank Northern Rock found itself short of money to pay its debts. When news of this became public, there was concern among the banks customers about the security of their deposits. Of course, with the Bank of England providing a financial backstop, the overwhelming majority of deposits were safe; yet some customers withdrew their funds regardless, presumably having decided that the cash would be safer in their own hands.

This may have begun as a slow drip of customers withdrawing their money, but it soon became a torrent; as it gained attention in the press, more customers saw what was happening and decided to follow suit. No one wanted to be the last one standing when the music stopped. So began the first run on a bank in the UK for 150 years.

By this point, with trust in the bank low and a norm established of extracting cash, no amount of reassurance from the bank could settle the public panic. On 22 February 2008, the British government announced that it would nationalize Northern Rock. Six months later, when the US investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed and wasnt bailed out, the global financial crisis exploded in earnest.

Even as the crisis unfolded, many experts and academics maintained that there wouldnt couldnt be a run on a bank in the developed Western world. This was not simply a matter of the law, or of history. This was a belief, hardbaked into conventional economic thought, that people would behave rationally: that they would not engage in behaviour that ran counter to their own interests. The loss of trust in the bank, despite the law, showed that trust was a matter of feelings and not just of facts. Traditional economic theories couldnt explain why a few malcontents withdrawing their cash could so rapidly become tens of thousands of people doing the same you shouldnt join someone you see behaving irrationally, after all.

Along with the emergence of the subprime mortgage bubble, and the seeming powerlessness of governments to stop the crisis once it had begun, failure of economic thought to come to grips with the behaviour unfolding led to the beginning of a more wholesale rejection of economics. Instead, people began to turn towards a fairly small subsection of the discipline behavioural economics that sought, through the marriage of economics and psychology, to explain and predict human behaviour better than either discipline could by itself.

Although the field had already caught on to a great extent in academia Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky published the foundational paper, Prospect theory, changed all of that. If the crisis showed that policymakers couldnt rely on the models of traditional economists, which had failed to predict the subprime mortgage problem and consumers reactions to it, Nudge gave both an alternative approach to understanding behaviour and, more importantly, suggestions about how to do things better next time. Determined to put these lessons to work, Sunstein joined the Obama administration to run the office of information and regulatory affairs one of the less well known, but most influential parts of the US government.

Over the last few years, governments around the world have sought out the guidance of Thaler and Sunstein and their followers and so-called Nudge Units have sprung up in droves.

The first of these was the British governments Behavioural Insights Team, or BIT, where we both worked Susannah for the last five years, and Michael for the last seven. BITs remit is to apply the new thinking coming out of behavioural economics and related fields to some of the complex problems faced by the UK government. In practice this often comes down to paying attention to how people actually approach decisions whether to withdraw all their money from their bank, for example, or whether to go to university rather than how we think they should approach decisions, or how they say they approach them.

This may seem obvious, but for many years this way of thinking was not common in the corridors of power: economists, and their theories of rational, selfish individuals, reigned supreme. When BIT first formed in 2010, it was groundbreaking for two reasons. First, it brought a more realistic model of human behaviour, based on psychological insights about how we really think, into the corridors of power. Second, it relied much less on theory, and much more on data, than a lot of what had gone before it bringing randomized experiments, like those used in medicine, into policymaking in a major way for the first time. This combination of scientific methodology and the use of government power to help people was what first attracted both of us to BIT.

Much of what has followed from the great recession, from Nudge and from the behavioural revolution in economics, focuses on our cognitive failures, or behavioural biases the shortcomings in our brain and the tricks it plays on us that lead us to behave as we do. There has been less focus, so far, on the complex tangle of social threads in which we are all entwined. Our aim with this book is to turn our gaze on this tangle, to try to understand its different components and how they can be influenced. At a basic level,