The Great Society Subway

Creating the North American Landscape

Gregory Conniff, Edward K. Muller, and David Schuyler

Consulting Editors

George F. Thompson

Series Founder and Director

Published in cooperation with the Center for American Places

Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Staunton, Virginia

The Great Society Subway:

A History of the Washington Metro

Zachary M. Schrag

2006 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2006

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Johns Hopkins Paperback edition, 2014

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as follows:

Schrag, Zachary M.

The Great Society subway : a history of the Washington Metro / Zachary M. Schrag

p. cm. (Creating the North American landscape)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8018-8246-X (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. SubwaysWashington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. 2. SubwaysWashington Metropolitan Area. 3. Local transitSocial aspectsWashington Metropolitan Area. I. Title. II. Series.

HE4491.W44W376 2006

388.42809753dc22 2005012141

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-1577-2

ISBN-10: 1-4214-1577-1

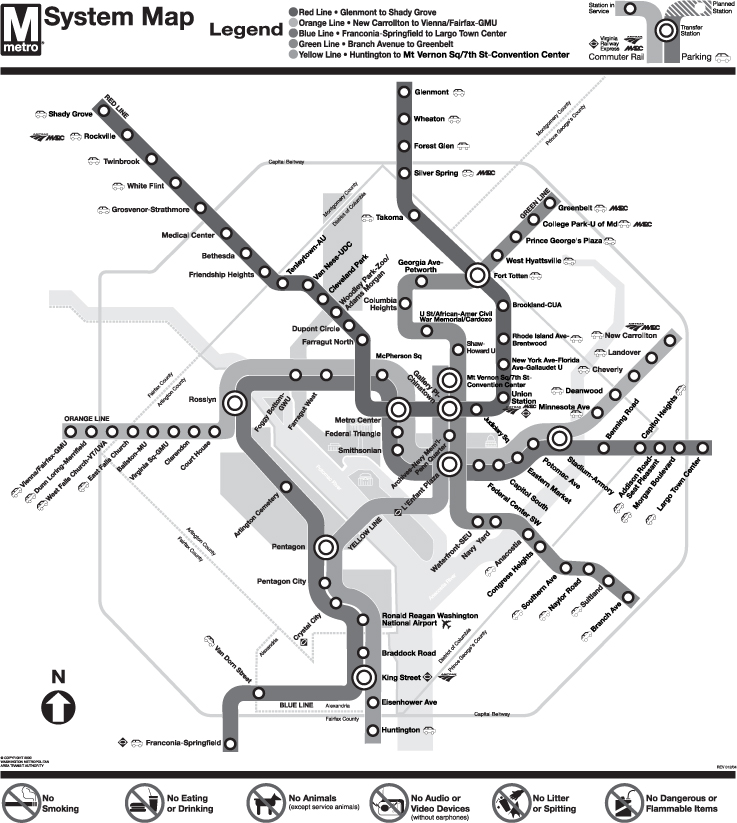

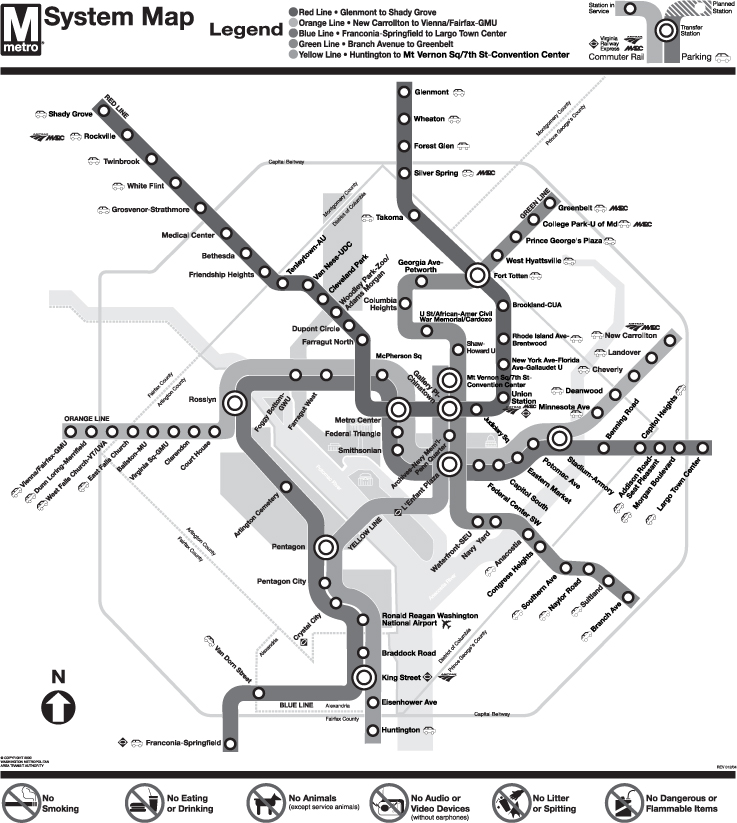

Frontispiece: The Washington Metro, 2004 (Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority)

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

For Rebecca

Contents

Preface

Traveling west from East Falls Church Station, the trains rolled just a short distance along the familiar route. Then they switched onto new tracks built into the median of the Dulles Access Highway before climbing and making a sharp left turn high above Route 123. From there, those on board could see the cranes and skyline of a growing city. Not Washington, but Tysons Corner, Virginia, the boomtown so long defined by its dependence on the car. In the 1960s and 1970s, planners had chosen not to send the Orange Line to Tysons. Now, in 2014, engineers were readying a sixth colorthe Silver Lineto become part of Washingtons Metro system.

In the absence of a Metro station, Tysons Corner, like so much of suburban America, had grown on an armature of interchanges and parking garages, making the area notoriously difficult to navigate on foot and prone to traffic jams. As the new Silver Line became real, with not one but four stations serving Tysons, planners and developers imagined new possibilities. The arrival of Metrorail service provides an opportunity to transform Tysons... from an edge city into a true urban downtown for Fairfax County, explained a new county plan. The remade Tysons should provide a better balance of housing and jobs, a transportation system that includes facilities for pedestrians, bicyclists and motorists, and a green network that links existing stream valley parks with open space and urban parks located throughout the area. If just a fraction of this vision were realized, Tysons would be unrecognizable. As the test trains ran in the winter of 2014, they passed Tysons Corners new hotels, office towers, and a rising twenty-six-story apartment building before continuing on to Wiehle Avenue in Reston, 11.7 miles from East Falls Church.

In time, the ride would last longer. Past WiehleReston East Station, crews were already at work on an additional 11.4-mile alignment. Scheduled to open in 2018 (or thereabouts), this Phase 2 of the Silver Line would carry passengers to Dulles Airport and beyond. The decision to extend Metro to Dulles had been controversial: building heavy rail in an established downtown was one thing, but could it make sense in Ashburn, Virginia, more than twenty-five miles from the U.S. Capitol? Regional and federal officials debated this question for years, and more than once the Silver Line seemed doomed. Dulles Project All but Dead, warned a Washington Post lead headline in January 2008. Yet the Silver Line staggered to life. In March 2009, construction began.

Nor was this the only possible expansion of Metro. While the Silver Line pushed the system to the outer suburbs, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) also looked inward, to the downtown core. Projecting growth of daily rail ridership to 1.05 million riders per day by 2040, planners warned of shoulder-to-shoulder, rush hour conditions across the system if no new tracks were laid. Matters would be particularly bad on the Orange and Silver lines, which threaded through the lone RosslynFoggy Bottom tunnel also used by the Blue Line. To add capacity, planners envisioned a second Rosslyn crossing to (of all places) Georgetown, which could then feed a new downtown route along M, N, or P Street.

Other projects in the works showed rail transit no longer just meant Metro. In December 2013, the District Department of Transportation tested the first streetcars to run in Washington, D.C., since the congressionally mandated end of streetcar service in 1962. They rolled down H Street NE, a commercial corridor that, like 7th and 14th streets NW, had been hit hard by the 1968 riots but had not enjoyed a Metro line to speed its recovery. If all went well, District officials explained, the H Street line could be the start of a twenty-two-mile streetcar system, to be built over twenty years. Meanwhile, Arlington and Fairfax counties moved forward with plans for a streetcar along Columbia Pike, and Maryland continued to consider a sixteen-mile light-rail line. This Purple Line, unlike the D.C. and Virginia streetcars, would operate primarily in an exclusive right-of-way, boosting its speed.

In all of these jurisdictions, planners hoped that surface rail could bring some of the benefits of heavy rail at a fraction of the cost. As an Arlington County website explained, while the county did not want enough density along the Pike to merit heavy rail, fixed-rail streetcars provide employers and developers with the sort of certainty that changeable bus routes cannot. They provide transit capacity that buses cannot. But buses found their place as well. In other parts of Arlington, such as Shirlington, and in other jurisdictions in the region, planners looked to local buses, bus rapid transit, and bicycles to offer yet more alternatives to driving. As it had decades earlier, the Washington region was investing billions in transit.

These projects would not be the same sort of collective effort that once unified the region. From 1969 through 2001, building Metro was a regional project, with the District, Maryland, and Virginia contributing to a common goal and each receiving new tracks in turn. The Silver Line, by contrast, was built not by WMATA but by the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, which operates Dulles Airport and, as significantly, the Dulles Toll Road. Of the $5.5 billion the Silver Line was expected to cost, planners counted on toll revenues to contribute 48.1 percent, airport funds 4.1 percent, the federal government 16.4 percent, and the Commonwealth of Virginia and Fairfax and Loudoun counties the remaining 31.3 percent. Though actual operation of the Silver Line would be up to WMATA, its construction was, in effect, not a regional project but a Virginia project. Similarly, three stations opened in 2004Largo, Morgan Boulevard, and New York Avenue (later renamed NoMaGallaudet U)had been funded by Maryland and the District of Columbia. The H Street and Columbia Pike streetcars and the Purple Line would constitute local connections to the regional Metro system.

Next page