BART

2016 by Michael C. Healy and San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Healy, Michael C., author.

Title: BART : the dramatic history of the Bay Area Rapid Transit system / Michael C. Healy.

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, 2016. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016025736| ISBN 9781597143707 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781597143813 (e-pub)

Subjects: LCSH: San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (Calif.)History. | Local transitCaliforniaSan Francisco Bay AreaHistory.

Classification: LCC HE4491.S45 H43 2016 | DDC 388.4/2097946dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016025736

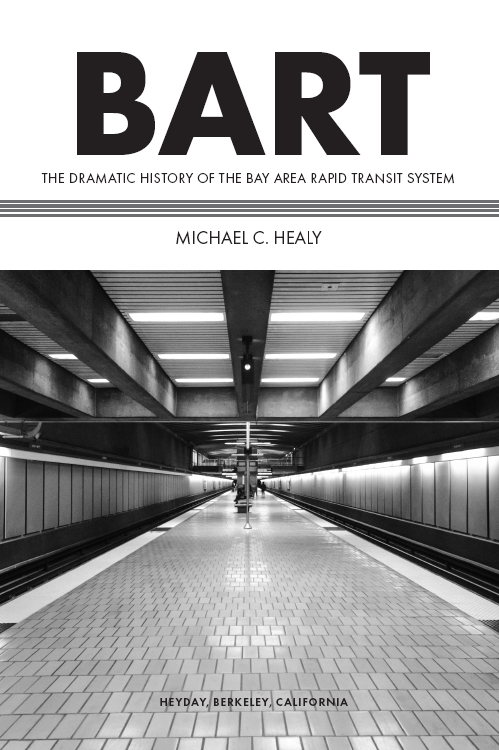

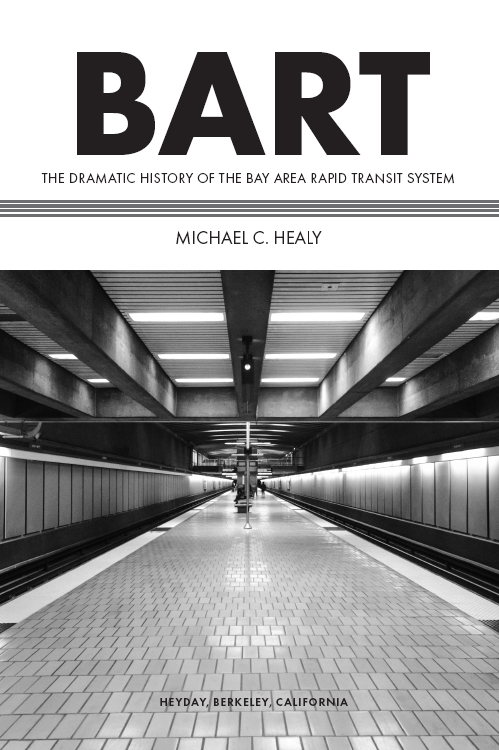

Cover Image: Photo by Thomas Hawk.

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram

Interior Design/Typesetting: Rebecca LeGates

Printed in East Peoria, IL, by Versa Press, Inc.

Previous page: Ashby BART Station by Franco Folini is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Image credits: All images courtesy of BART except p. 28, courtesy of John Harder, and p. 182, courtesy of David Lance Goines.

Orders, inquiries, and correspondence should be addressed to:

Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, CA 94709

(510) 549-3564, Fax (510) 549-1889

www.heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the memory of Marvin E. Lewis, BARTs early pioneer; to the memory of B. R. Stokes, who guided the building of the system; to my wife, Joan Van Horn, whose knowledge of some of the history was invaluable; and to all the men and women who make BART work each and every day.

CONTENTS

by John King

FOREWORD

The evidence of how well BART has shaped and served the Bay Area is that, these days, we take it for granted. We complain about having to stand. We complain about the crowded escalators. We grumble if the doors close before we can rush on, and we grouse if someone blocks the door to keep them from closing once were inside. If there isnt a stop within an easy walk of where were headedwhy not?

In essence, were disgruntled because weve come to rely on this constantly evolving system with forty-five stations and 107 miles of trackthe real-life version of the original promise of a mass transportation service that is at least as fast, as comfortable, and as cheap to ride as the private automobile. Those words are from the original consultant study presented to the state legislature in 1956, a rosy preamble to the convoluted and often confounding saga that Mike Healy tells so engagingly in the pages that follow.

Healy is the ideal raconteur to spin the yarn, having served BART as its spokesman for decades before retiring in 2005. He was there for the opening in 1972 and the years of problem-solving that followed. His older coworkers were the bureaucrats who had pushed forward tenaciously through the prior decade of missed deadlines and budget strains, the hype of space-age design and the reality of old-school politics. Pick your anecdote from the abundance, starting with the incongruous scene at a Martinez breakfast counter in 1962 as the mayors of San Francisco and Oakland pitched woo to a tight-lipped Contra Costa County supervisor. The latter was the swing vote on whether residents of that county, then largely rural, would be presented with a ballot measure to finance the system. (Not even Healy knows exactly what was said, but the rest is history.)

Now look past the entertainment factor: this is an important story that Healy tells, and a timely one, too.

In todays California we like to think either that nothing large should be attempted because it might have troublesome side effects, or that nothing will get done because opponents can find too many ways to hobble progress. But the history of BART is a reminder that this has always been true. Big plans stir big opposition. Every bump in the road is portrayed as the beginning of the end. Long-term planning confronts short-term grandstanding. The same Oakland mayor who lobbied for the overall system later forced BART to reroute a portion of his downtowns subway around a popular hardware store. By the opening day, the hardware store already had gone out of business and thanks to the tighter underground alignment, Healy tells us, riders for years endured the screaming sound of wheel flanges scraping the rail as trains negotiated the curve.

In hindsight, obviously, the original alignment was better. Just as, in hindsight, San Mateos board of supervisors made a bad call in 1961 when they pulled out of the proposed system and delayed service south of San Francisco for more than twenty years. But this is how the real world works when something ambitious is at stake: you keep moving forward any way that you can, rather than stop until everything is ideal. The reason we can put our ticket through the turnstile in Richmond or Pittsburg or Pleasanton or Fremont and step off the train at San Francisco International Airport is because hundreds of smart, determined people ignored headlines and lawsuits and technological strains to summon the system into existence and then get the trains to run (mostly) on time.

Why does this matter now? Simple. Try to imagine the Bay Area without BART, and Ill wager that you come up short. The system ties together communities and has allowed Bay Area residents the option of an expansive car-free lifestyle. Neighborhood centers such as Rockridge in Oakland were revived by BARTs presence, exactly the opposite of the apocalyptic warnings from the political left that saw the system as nothing more than a corporate plot to funnel workers into San Franciscos Financial District. As for projections that trains would be vacant except during commute hoursnot far from the truth early onnow it can seem crowded at most hours of the day. This is how we get around whenever we can, our mode of choice for outings and events. Outings and events that, often, choose their location so that BART is close by. The region and its rapid transit are inseparable, a bond that only grows stronger as once placid suburban cities add transit villages next to stops.

Yes, there were mishaps along the way. Test cars crashed and homeless people camped out in bicycle lockers. Some marketing forays were ill conceived, including a brief experiment in the early 1980s when trains could be chartered for private events, complete with food and beverages. The system also was put to the test by cultural changes; Healy is quietly eloquent in detailing how and why BART became the first transit system to provide elevator service to train platforms. The reason in large part was the crusade launched by Harold Willson, who had moved to the Bay Area after being paralyzed in a coal-mining accident in West Virginia and made it his mission to ensure BART was accessible to people like him. Willson possessed not only a hardened determination but also an engaging charm, Healy writes, and in 1968, the board came around.

This is history that we need to remember. Not just for historys sake but for what might lie ahead.

We live in an era when map-altering endeavors are in the works, from high-density housing in suburban downtowns to the effort to link San Francisco and Los Angeles with high-speed rail. Without fail, theyre attacked as destructive boondoggles sure to mar our quality of life. Sometimes we need to say no, to be sure. Other times, though, we need to dream. The legacy of BART is that large-scale audacity can succeedand the Bay Area is better as a result.

Next page