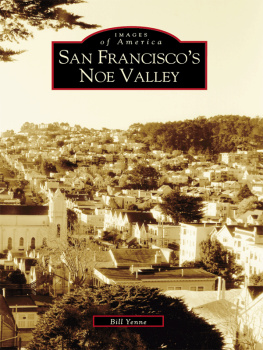

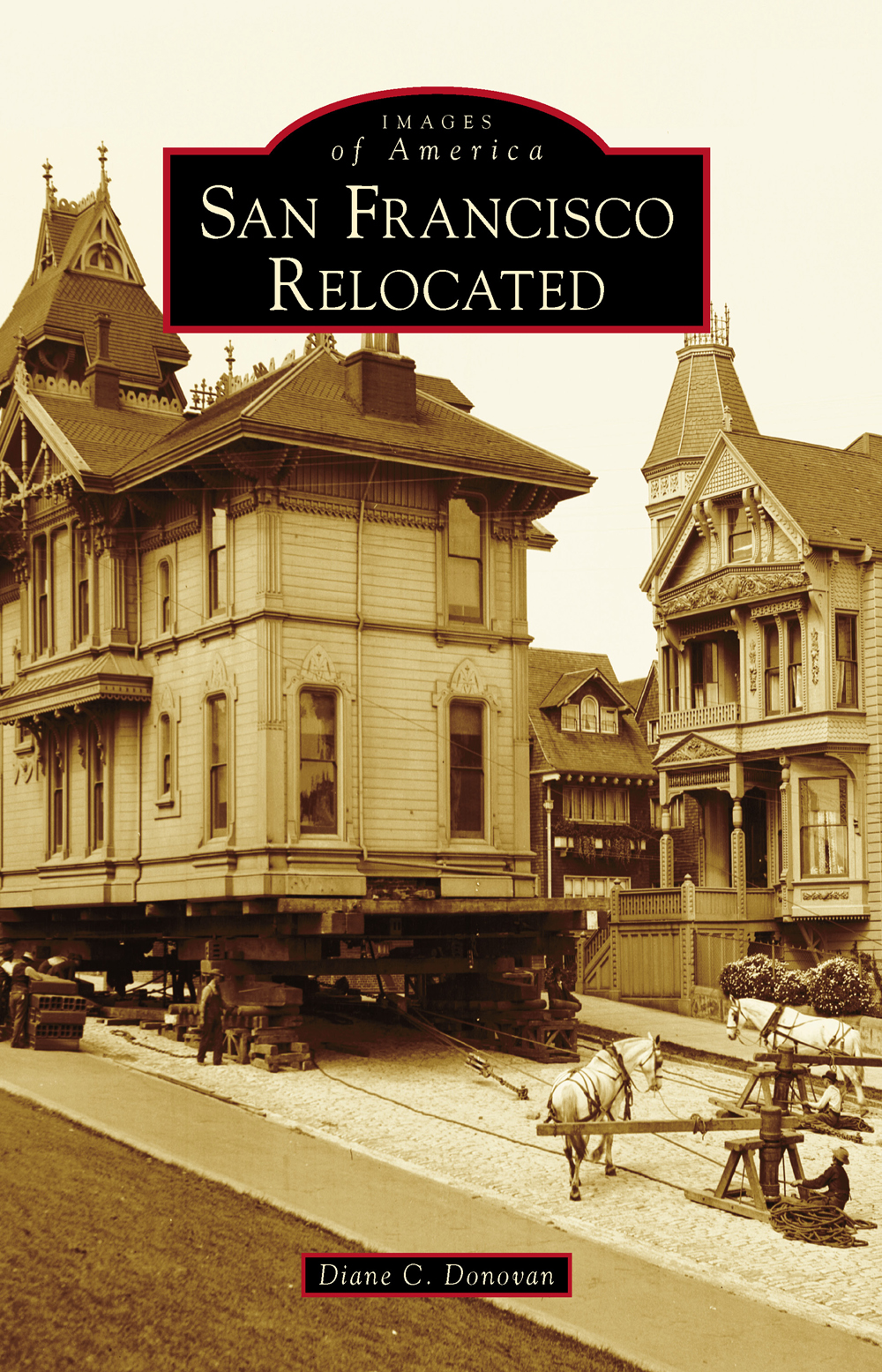

IMAGES

of America

SAN FRANCISCO

RELOCATED

ON THE COVER: This 1908 photograph depicts a team of horses moving a Victorian house. In the early 1900s, two-horse teams were commonly used to move buildings. First, the house was jacked up off its foundation and supported by heavy wooden beams. Greased beams, serving as runners, helped the building inch along. As it progressed down the street, the planks and ties left behind were manually picked up by workers and carried to the front of the moving building to become the new track. A capstan (basically, a drum) was mounted in the middle of the street, and a pulley connected the structure to a cross beam between the runners. The horses walked around in a circle and pulled on a pulley connected to the capstan, stepping over the cable. The cable wound up on the capstan, and the house moved along. The horse-pull method was favored into the 1930s, even though gasoline-powered trucks were available, because horses could simply step over the cable each time, which was something a truck could not do. San Francisco Heritage identified this photographs location as Steiner Street approaching Washington Street. (Courtesy of the Milwaukee Public Museum.)

IMAGES

of America

SAN FRANCISCO

RELOCATED

Diane C. Donovan

Copyright 2015 by Diane C. Donovan

ISBN 978-1-4671-3371-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439653678

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015931845

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Bill Donovan, who always said I could do anything, and Beni Bacon, whose support, computer, and photography skills helped make this book happen

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Perhaps the most surprising part of producing an Arcadia book is the collaborative effort involved; not just between people who are already familiar to one another, but also between strangers who come together with a shared common interest in contributing images and facts to a historical investigation.

Through this shared effort, history becomes a living, breathing process, changing with the debates, fact finding and fact checking, research discoveries, and dialogue surrounding each book chapters evolution.

San Francisco Relocated would not have happened without the generous time, information, and images shared by this growing circle of new friends.

I am indebted to Vicky Walker of Bernal Heights Association for her ongoing support and familiarity with Arcadias processes and requirements. Also, I am immensely grateful for the assistance of the following people: photographer Dave Glass, for his many unique images of the Western Additions Victorian house moves; collectors John Freeman and friend Glenn Koch, for their extensive research and images; Peter Linenthal, of the Potrero Hill Archives Project, for images and support; Paul Rosenberg, for his enthusiastic kick-off for the book; and Evelyn Rose, of the Glen Park Neighborhood History Association, for her wholehearted encouragement.

Fellow Arcadia author Lorri Ungaretti generously contributed her time and provided key encouragement at a point of despair, Mike Shea contributed many images and much enthusiasm, Woody LaBounty, of Western Neighborhoods Project, provided a treasure trove of images and information, and Philip Brent Digital Art and Photography worked a bit of magic to return many of these images to life. Friend Barry Lawrence provided much expertise and insight on the photograph permission process.

And, let us not forget that were it not for my childhood landlord Joseph Carusos willingness to chat with a small child about his house-moving pursuits, as well as his familys enthusiastic encouragement for sharing his efforts and the origins of his house-moving involvement, the entire story of the Portola District and other small-time neighborhood movers might have remained untold.

It truly takes a village to produce an Arcadia book; it is an intersection of community, history, and generosity at its best. San Francisco Relocated could not have been written without this communitys support, and I thank you all!

INTRODUCTION

Why write a book about San Franciscos house-moving past? And why move a house in the first place? Who were these urban cowpokes, as one reporter described them, whose businesses revolved around picking up and moving houses? All three questions ultimately formed the nexus of San Francisco Relocated.

I was about nine years old when my parents moved to the Portola District, renting a common row house that seemed to hold no special attributes. It was not a Victorian, it could not be described as ornate by any manner of means, and it did not stand out from any other house on the block. It was sandwiched beside two other houses with the usual San Francisco propensity for allowing only a few inches of space between buildings.

Had it not been for hours of hanging on the back fence listening to our landlord tell stories about how he had made a thriving business out of buying up houses that needed moving and relocating them onto vacant lots, I would have never even known that a building could be picked up and moved.

Our house on Sweeny Street was one of those houses; its twin next to us was another. Joseph Caruso moved numerous homes throughout the Portola District, his center of operations. He was just a small-time contractor who, it turned out, was one of the last San Francisco house-moving entrepreneurs in the waning years of the citys moving history.

Now fast forward 40 years, when an amazing photograph of a two-story Victorian house being moved downhill via a team of draft horses and some wooden rollers caught my eye, releasing a floodgate of memories of Joseph Caruso and his unusual business.

As I investigated San Franciscos moved-building history, I was amazed to discover that the citys house-moving adventures were second only to Chicagos. It is also astonishing to note that the heyday of San Franciscos relocation actually occurred between 1850 and 1920, when so many houses were moved that San Franciscans came to consider them a nuisance and complained about the street-hogging houses that wandered irresponsibly from block to block in search of new lots as the city expanded and constantly revised its sidewalks, boundaries, and grid lines.

Mark Twain, one of the loudest (and most literary) of these protesters, used his position as a local reporter for San Franciscos Daily Morning Call to document the wayward buildings and their troublesome journeys through the streets of San Francisco: An old two-story, sheet-iron, pioneer, fire-proof house, got loose from her moorings last night, and drifted down Sutter Street toward Montgomery.

An 1868 article in the California Alta documented the damage done to cobblestones and pavement by house-moving operations as follow: The business of buying those old shells, moving them out of the fire limits, repairing or patching them up, and selling them on long credit, at round prices, has become a regular trade, which is followed by a number of persons with profit to themselves, but loss to the general public. The California Alta called for regulation, fines, and even imprisonment.

And sometimes, the city supervisors took matters into their own hands, as when they decreed that, on Golden Gate Avenue, no permit shall ever be issued allowing the moving of any house along said street for any distance whatever, and no housemoving shall, ever, be done on said street, either along, upon or across the same.

Next page