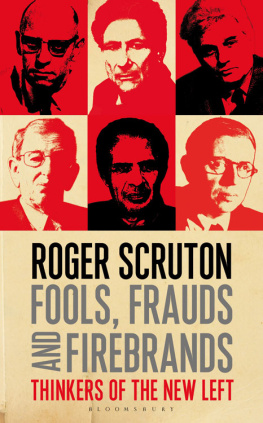

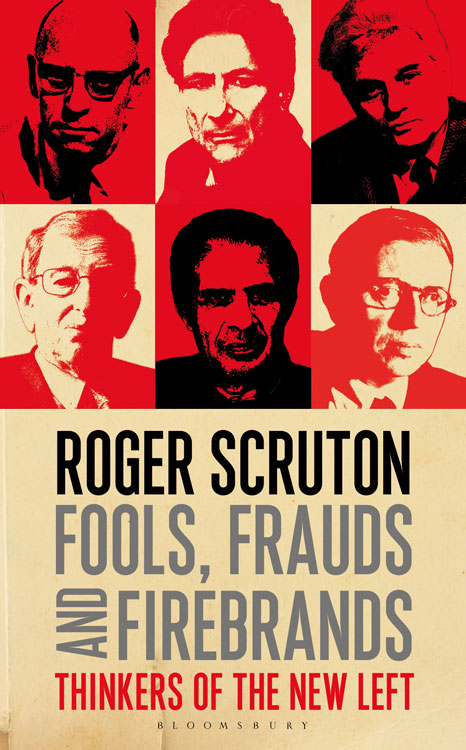

FOOLS, FRAUDS AND FIREBRANDS

Thinkers of the New Left

Roger Scruton

In a previous book published in 1985 as Thinkers of the New Left, I brought together a series of articles from The Salisbury Review. I have reworked the original articles, cutting out writers like R. D. Laing and Rudolf Bahro who have nothing to say to us today, and including substantial new material devoted to developments that are increasingly influential for example the stunning nonsense machine invented by Lacan, Deleuze and Guattari, the scorched-earth attack on our colonial inheritance by Edward Said, and the recent revival of the communist hypothesis by Badiou and iek.

My previous book was published at the height of Margaret Thatchers reign of terror, at a time when I was still teaching in a university, and known among British left-wing intellectuals as a prominent opponent of their cause, which was the cause of decent people everywhere. The book was therefore greeted with derision and outrage, reviewers falling over each other for the chance to spit on the corpse. Its publication was the beginning of the end for my university career, the reviewers raising serious doubts about my intellectual competence as well as my moral character. This sudden loss of status led to attacks on all my writings, whether or not they touched on politics.

One academic philosopher wrote to Longman, the original publisher, saying, I may tell you with dismay that many colleagues here [i.e. in Oxford] feel that the Longman imprint a respected one has been tarnished by association with Scrutons work. He went on in a menacing manner, expressing the hope that the negative reactions generated by this particular publishing venture may make Longman think more carefully about its policy in the future. One of Longmans best-selling educational writers threatened to take his products elsewhere if the book stayed in print and, sure enough, the remaining copies of Thinkers of the New Left were soon withdrawn from the bookshops and transferred to my garden shed.

I have naturally been reluctant to return to the scene of such a disaster. Gradually, however, in the wake of 1989, a measure of hesitation has entered the left-wing vision. It is now common to accept that not everything said, thought or done in the name of socialism has been intellectually respectable or morally right. I was perhaps more than normally alert to this possibility on account of my involvement, at the time of writing, with the underground networks in communist Europe. That involvement had brought me face to face with destruction, and it was obvious to most people who troubled to expose themselves to this destruction that leftist ways of thinking were the ultimate cause of it. Thinkers of the New Left appeared in samizdat editions in Polish and Czech, and was subsequently translated into Chinese, Korean and Portuguese. Gradually, and especially after 1989, it became easier for me to express my vision, and I have allowed my publisher, Robin Baird-Smith, to persuade me that a new book might bring relief to students compelled to chew on the glutinous prose of Deleuze, to treat seriously the mad incantations of iek, or to believe that there is more to Habermass theory of communicative action than his inability to communicate it.

The reader will understand from the above paragraphs that this is not a word-mincing book. I would describe it rather as a provocation. However, I make every effort to explain what is good in the authors I review as well as what is bad. My hope is that the result can be read with profit by people of all political persuasions.

In preparing this book for the press I have been greatly helped by comments and criticisms from Mark Dooley, Sebastian Gardner, Robert Grant and Wilfrid Hodges, all of whom are innocent of the crimes committed in the following pages.

Scrutopia, January 2015

The modern use of the term left derives from the French Estates General of 1789, when the nobility sat on the kings right, and the third estate on his left. It might have been the other way round. Indeed, it was the other way round for everyone but the king. However, the terms left and right remain with us, and are now applied to factions and opinions within every political order. The resulting picture, of political opinions spread in a single dimension, can be fully understood only locally, and only in conditions of contested and adversarial government. Moreover, even where it captures the outlines of a political process, the picture can hardly do justice to the theories influencing that process, which form the climate of political opinion. Why, therefore, use the word left to describe the writers considered in this book? Why use a single term to cover anarchists like Foucault, Marxist dogmatists like Althusser, exuberant nihilists like iek and American-style liberals like Dworkin and Rorty?

The reason is twofold: first the thinkers I discuss have identified themselves by that very term. Second, they illustrate an enduring outlook on the world, and one that has been a permanent feature of Western civilization at least since the Enlightenment, nourished by the elaborate social and political theories that I shall have occasion to discuss in what follows. Many of my subjects have been associated with the New Left, which rose to prominence during the 1960s and 70s. Others form part of the broad ground of post-war political thinking, according to which the state is or ought to be in charge of society and empowered to distribute its goods.

Thinkers of the New Left was published before the collapse of the Soviet Union, before the emergence of the European Union as an imperial power and before the transformation of China into an aggressive exponent of gangland capitalism. Thinkers on the left have naturally had to accommodate those developments. The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the weakness of socialist economies elsewhere gave a brief credibility to the economic policies of the new right, and even the British Labour Party climbed on to the bandwagon, dropping Clause IV (the commitment to state ownership) from its constitution and accepting that industry is no longer the direct responsibility of government.

For a while it even looked as though there might be an apology forthcoming, from those who had devoted their intellectual and political efforts to whitewashing the Soviet Union or praising the peoples republics of China and Vietnam. But the moment of doubt was short-lived. Within a decade the left establishment was back in the driving seat, with Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn renewing their intemperate denunciations of America, the European left regrouped against neo-liberalism, as though this had been the trouble all along, Dworkin and Habermas collecting prestigious prizes for their barely readable but impeccably orthodox books, and the veteran communist Eric Hobsbawm rewarded for a lifetime of unswerving loyalty to the Soviet Union by his appointment as Companion of Honour to the Queen.

True, the enemy was no longer described as before: the Marxist template did not easily fit the new conditions, and it seemed a trifle foolish to champion the cause of the working class, when its last members were joining the ranks of the unemployable or the self-employed. But then came the financial crisis, with people all around the world thrown into comparative poverty while the seeming culprits the bankers, the financiers, and the speculators escaped with their bonuses intact. As a result, books critical of market economics began to enjoy a new popularity, whether reminding us that real goods are not exchangeable (Michael Sandel:

Next page