Introduction

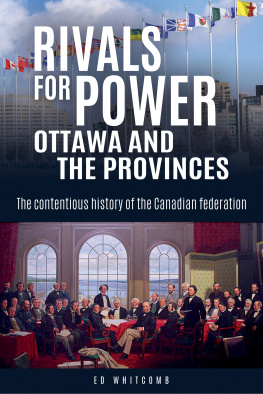

At some stage of a project, most writers probably find themselves beset by doubts about what it is they are doing. With a subject as arcane as Canadian fiscal federalism by which we mean revenue transfers from the federal government to provincial governments such apprehension accompanied almost every one of my early daily encounters with keyboard, blank screen, and piles of research material. Would anyone actually care about the history of federal transfers and the contemporary attack on equality of opportunity for Canadas citizens? I worried that this undertaking would be dismissed as just one more plea for increased federal handouts to confederations losers.

Then I picked up a copy of Macleans magazine for October 31, 2011, featuring a review of Nationmaker , volume two of journalist Richard Gwyns biography of John A. Macdonald, the countrys first prime minister and Canadas dominant political figure for some forty years. Macleans , like most of the Canadian news media, has embraced neo-conservative ideas, typified by the front page of the aforementioned Halloween edition, which declared that The Occupy Wall Street movement has it all wrong: Andrew Coyne on why the rich arent the problem.

Neo-con journalists do not limit their defence to rich people; they extend it to rich provinces. The idea that residents of one Canadian province would collectively pay more in federal taxes to the federal government than they get back in federal services (and vice versa) is repugnant to them. The notion that some of the federal taxes paid by Albertans or Ontarians would help to raise the standard of public services in Prince Edward Island or Quebec is equally heinous. In Nationmaker , the Macleans reviewer Paul Wells found evidence that this practice has been going on almost since Canadas difficult birth in 1867.

It dates back to the 1869 parliamentary debate on the Macdonald governments bill to extend better terms to Nova Scotia. The opposition Liberals under Ontarios Edward Blake fought the legislation, even though (as detailed in chapter one) the better terms paled beside those claimed by Ontario at confederation. It also should be noted that they were offered to Nova Scotia to quell a serious movement to take the province out of confederation. But to Macleans scribe Wells, the better terms set a pattern that persists to this day a taxpayer-funded salvage operation at Ontarios expense, a scenario that the Ontario premier in 2011, Dalton McGuinty, would easily recognize.

So, thanks Macleans . It is well worth taking a run at setting the record straight on the history of fiscal federalism, and specifically the idea that governments should work together to ensure a standard level of social services to all Canadians equal citizenship without erasing provincial boundaries. Like most Canadians, I have personal attachments across the country. I have lived in both the east and the west, and have family in Ontario and Quebec. I have never heard anyone openly challenge the notion of equal citizenship or argue that there should be different classes of public services available to Canadians depending on the province where they reside. Yet that is the implication of much of the current discourse, as politicians from wealthier provinces begrudge transfers from Ottawa to the less-wealthy provinces, and the pundits and neo-conservative think-tanks callously classify the provinces as makers or takers. Canada was formed from a union of provinces with widely varying levels of wealth. For a time, we seemed to accept the idea that the level of public services in each province should be dictated by the level of wealth. But we eventually rejected that ungenerous way of thinking and built a transfer system that strived to achieve equal citizenship. That system is in jeopardy.

Lets start with Ontario, past and present. The events that led to confederation have been much chronicled, dissected, interpreted, and reinterpreted. In that flood of prose there is consensus that Ontario (then known as Canada West) was the prime mover and beneficiary of confederation. Economists and historians as diverse as British Columbias Christopher Moore, Ontarios F.H. Underhill, and New Brunswicks W.Y. Smith have subscribed to the view that Ontario was the key promoter and big winner from confederation, and throughout the century that followed.

These days, Ontario is not as satisfied with confederation as it used to be, its industrial structure (built with the help of a tariff wall) threatened in a world of globalization, out-sourcing, and Canadas growing status as a petro-state. Its complaints about fiscal transfers tend to be dismissed as whining in some quarters, but when its leaders attack federal transfers to provinces (other than Ontario), they find an echo chamber in media outlets and neo-conservative think-tanks such as the Fraser Institute.

One of the Frasers early publications was a 1978 collection of essays featuring Avenues of Adjustment: the Transfer System and Regional Disparities by Thomas J. Courchene, a distinguished Ontario-based economist and expert on revenue transfers in general and equalization in particular. That piece suggesting that federal transfers actually contributed to regional disparities rather than mitigating them has resonated over the years with neo-con think-tanks, including the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies, born in 1994.

Although it was promoted by outsiders, AIMS was surprisingly well received locally. Over the years, its large board of directors has included not only the regions corporate elite, but a cross-section that at various times brought in university presidents, co-operators, food chain executives, and public utility managers in other words, folks who rely for their livelihood on government expenditures or what the economists call place prosperity. AIMS has cranked out dozens of reports over the years that, if taken seriously by policymakers, would create mass out-migration, damaging the bottom line of many AIMS directors. One of the institutes first efforts, Looking the Gift Horse in the Mouth (discussed in chapter ten), advised people in the Atlantic provinces to welcome a reduction in federal transfers, not dread them. Even though the methodology behind this advice was refuted by a trio of economists, the report stood, sixteen years later as proof of AIMSs contention that federal transfers are the help that hurts.

Frank McKenna, premier of New Brunswick from 1987 to 1997, expressed a similar sentiment in a speech to the 1993 Couchiching Conference, stating that the generosity of Canada has in many ways been the principle impediment to our growth. Premier Danny Williams of Newfoundland ventured into the same territory in 2008, when that province became ineligible for equalization as a result of oil royalties finally flowing in from its offshore oil deposits. Williams declared that now we can hold our heads high and feel very good about it. The fact that Newfoundland had been the butt of a half-century of putdowns for its economic weakness partially excuses Williamss response. But what does it say about Newfoundlands erstwhile equalization-receiving partners who lack a nearby economically exploitable petroleum resource? That they should continue to hang their heads in shame? Maybe acceptance of the neo-conservative analysis functions in the same way as the confessional our leaders admit our sins of dependency, endure a lecture from critics in Alberta or Toronto at the National Post or some think-tank, recite a few mantras about self-reliance, then return to business as usual.

Many from across the political spectrum subscribe to the notion that some combination of pulling up of bootstraps, enlightened economic development policy, and pumping oil and gas out of the ground will end the curse of dependency. So far, only the latter factor has been shown to be true, but in a world moving away from fossil fuels, striking oil can hardly be relied upon for deliverance. Leaders of the past had a more realistic view. They recognized that economic strength was distributed unequally across the country, but that the federal government had a responsibility to see that its benefits were shared. As 1950s-era federal finance minister Douglas Abbott put it: No federal-provincial fiscal arrangement can alter the facts of geography or change the location of rich natural resources, but federal-provincial arrangements should be designed to moderate, rather than aggravate, these regional inequalities of wealth and resources.