This book inaugurates the

CLIFTON AND SHIRLEY CALDWELL TEXAS HERITAGE SERIES

Books about Texans and their architecture, built environment, and photography, as well as historic preservation and the flora and fauna of the state

In 1940 the Central Texas congressional candidate for reelection, Lyndon B. Johnson, capitalized on recent New Deal developments in his Tenth District by encouraging publication of The Highland Lakes of Texas. This planning guide from federal and state partner-agencies illustrated through charts and graphs, and pen-and-ink scenes, the sweeping opportunities offered by new lakes, new highways, and new parks along the Colorado River. That fall, Civilian Conservation Corps Co. 854 commenced work on Inks Lake State Park, and transformed this model American recreation landscape into reality. National Park Service, Lower Colorado River Authority, and State Parks Board

PARKS FOR TEXAS

Enduring Landscapes of the New Deal

JAMES WRIGHT STEELY

University of Texas Press

Austin

Copyright 1999 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 1999

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Steely, James Wright.

Parks for Texas : enduring landscapes of the new deal / James Wright Steely.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN: 978-0-292-72237-8

1. ParksTexasHistory. I. Title.

SB482.T4S74 1999

333.78'3'09764dc21 98-28537

ISBN 978-0-292-75884-1 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-78699-8 (individual e-book)

DOI 10.7560/777347

After all, nature has to give some help in establishing a state park. It requires more than a cow pasture and an excited chamber of commerce to make a park go.

State Representative W. R. Chambers, Dallas Morning News, 28 August 1945

For cheerfully taking the family on summer vacations to state parks and for explaining the difference between CCC and WPA, this work is in memory of Thomas Brazelton Steely Sr.

And to honor the hands and hearts of those who created the New Deal state parks this work is dedicated to The Alumni of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

PHOTO SECTIONS

TABLES

AUTHORS NOTE

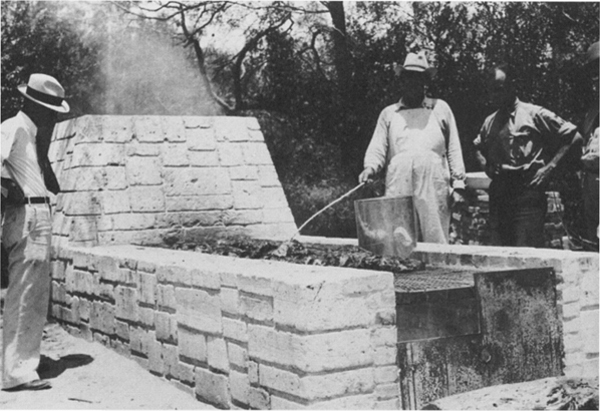

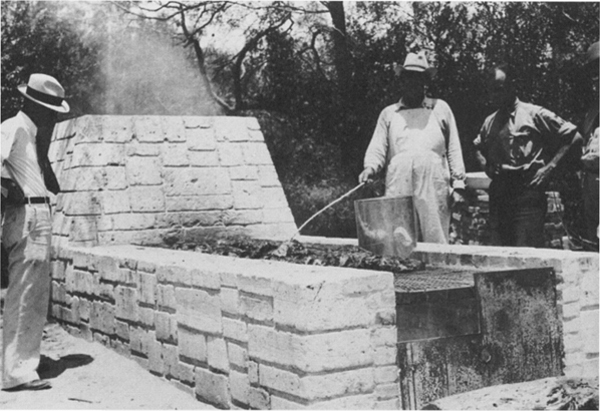

New Deal parks had aged some twenty years when the author first encountered their rustic cabins and outdoor cookers, such as this giant pit grill directed by summertime chefs about 1935 at Lake Corpus Christi State Park. If depression era Americans expressed dismay at relief workers creating recreation parks for the automobile class, their common experiences in the Second World War soon enough expanded the middle class to envelop even former CCC enrollees. By the 1950s, war veteransnow a class unto themselvesall brought their children of the baby boom to these state parks for summer vacations. Their campfire yarns might center on relatively recent war experiences, but their outdoor cooking intentionally rekindled traditions of pioneer days and brought yet another generation into contact with the great outdoors. Harpers Ferry Center, National Park Service

On the terrain motives become clear...Barbara Tuchman, The Historians Opportunity (1966) from Practicing History (Knopf, 1981), p. 61.

INSPIRATION

This work began a long, long time ago with a small boy in a state park, climbing up rough stone walls of a mountain cabin, all the way to its roof. Who could build such a perfect house? Later a job took the young man to other state parks, offering similar cabins, with fireplaces inside, too. Why did these perfect houses appear hundreds and thousands of miles from each other? Answering these questions led years later to a masters thesis, and further discovery of a seemingly endless inventory of parks to visit throughout the country. The answers continue to emerge, deep in lonely files and archives, and in the worn faces and bright eyes of the aging fellows who indeed built these perfect houses.

As friend John Jameson prepared an expanded work on Big Bend National Park, he encouraged his editor at the University of Texas Press to read that state-park thesis to find out who built some of those perfect houses in the Chisos Basin. From that introduction came this book assignment. Here the questions expanded to: where did the idea for state parks come from? who planned these parks? how were they financed? when did the concept of a park system appear? what determined the location of each park? why do these places endure?

Oddly enough, most of these questions concerning Texas state parks have never been answered, at least not in print, nor all in one place. Delightful storiesand some downright mythshave served as official answers for many years. For example:

from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1925: On a golden afternoon of the war year 1916, Mrs. Isabella Neff called her son, Pat, out to the old homestead near Waco and asked him to write the provisions of her last will and testament.... That 10-acre pecan grove along the banks of the Leon River, [she instructed Pat]... I wish to give my State for a permanent park.

from an internal history of the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department in 1968: Miriam A. Ferguson signed [a] bill creating Texas State Parks Board in 1925 (39th Leg.) and appointed 1st Board with Pat Neff as chairman.

The truth, as it is available in surviving documents, oral histories, and the parks themselves, is of course much more interesting than these expedient fabrications. This work originally encompassed a more complete accounting of Texas state parks and the State Parks Board, not always one and the same. But because the early history is mostly political, and not exactly one of concrete accomplishment, it now stands separately. Because the extraordinary development of facilities made possible during Franklin Roosevelts New Deal offers a most complete explanation for the state parks still enjoyed today, this volume concentrates on that depression-era episode.

BACKGROUND

As this story unfolds, the reader should keep a few eccentricities of Texas politics in mind, and be aware of peculiarities in this narrative.

Texas politicians in the early to mid-twentieth century hailed with few exceptions from the Democratic party, although the party itself acknowledged many diverse factions, and some outright renegades.

Texas elections for state office occur in even-numbered years, with late spring primaries and sometimes a summer primary runoff or two. Until the last generation or so, Democratic candidates surviving the last runoff had effectively won the office; the November general election served as mere ceremony and attracted large turnouts only in presidential election years.

Texas governors, like state representatives and congressmen, until 1975 stood for election every two years. With three exceptionsWilliam Hobby, Miriam Ferguson, and Ross Sterlingevery governor between Reconstruction and the Second World War won two consecutive terms; most served four full years.

Elected state officials take office, and the Texas legislature begins its 120-day (after 1930) regular session, in January of odd-numbered years. Any number of thirty-day called or special sessions may be held during the two following years, at the discretion of the governor and technically only to address topics identified by her or him.

Next page