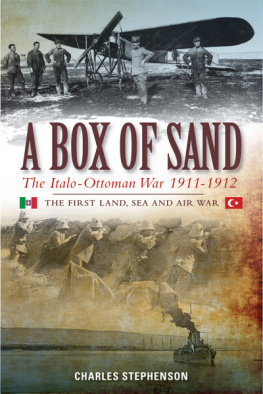

Tripoli is nothing more than an immense

and valueless box of sand.

GAETANO SALVEMINI, AUGUST 1911.

Published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Tattered Flag Press

11 Church Street

Ticehurst

East Sussex TN5 7AH

England

www.thetatteredflag.com

Tattered Flag Press is an imprint of Chevron Publishing Ltd.

A Box of Sand

Charles Stephenson

All rights reserved. No part of this book maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic, or mechanical including byphotocopying or scanning, or be held onthe internet or elsewhere, or recorded orotherwise, without the written permissionof the publisher.

Jacket Design and Typeset: Mark Nelson, NSW

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A Catalogue Record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-9576892-2-0

EPUB ISBN: 978-0-9576892-7-5

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom Copyright

Illegal copying and selling of publicationsdeprives authors, publishers and booksellersof income, without which there would beno investment in new books. Unauthorisedversions of publications are also likely to beinferior in quality and contain incorrectinformation. You can help by reportingcopyright infringements and acts of piracyto the Publisher or the UK Copyright Service.

For more information on books published by Tattered Flag Press visit

www.thetatteredflag.com

This book is dedicated to the

Axons: David, Tracey, Isabel

and William.

The Author

Charles Stephenson is a naval and military historian and is the author of several books including The Admirals Secret Weapon: Lord Dundonald and the Origins of Chemical Warfare (2006), Germanys Asia-Pacific Empire: Colonialism and Naval Policy, 1885-1914 (2009), and (as Consultant Editor) Castles: A Global History of Fortified Structures: Ancient, Medieval & Modern (2011). He is also responsible for the two works that (thus far) comprise The Samson Plews Collection; The Face of OO (2013) and The Niagara Device (2015). He lives in Flintshire, North Wales.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

O N 29 September 1911 Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire and proceeded to attempt the conquest of that Empires North African vilayet, or province, of Tripoli (now Libya). The resultant conflict, dubbed variously, by English writers, as the Italo-Turkish, the Turco-Italian or the Tripolitan War, was to Italians the Guerra di Libia (The Libyan War) and has come to be called in Turkish Trablusgarp Sava (The War of Tripoli) or Osmanl- talyan Harbi (Ottoman-Italian War).

The recently unified (1861) Kingdom of Italy sought, on the fiftieth anniversary of its founding, to conquer this largely barren territory for purely jingoistic purposes. Italy was a state on the rise with pretensions to Great Power status, and already the possessor of a small empire in East Africa. Conversely, the Ottoman Empire was a state in decline that had been losing territories to other powers, not all of them deemed Great, for a long period of time. This steady loss of Ottoman territory led to the advent of the Eastern Question, which concerned itself mainly with the matter of what might, or should, happen to the Ottoman Balkan territories if and when the Empire disintegrated? Should this occur then the potential for conflict between, in particular, the Great Powers of Austria-Hungary and Russia was extremely high. The Question, at bottom, revolved around managing Ottoman decline in such a way as to obviate that potential.

The Great Powers were, by 1911, divided, both formally and informally and with much equivocation, into two blocs; the Triple Alliance of Austria-Hungary, Germany and Italy, and the Triple Entente consisting of Britain, France and Russia. Italy though was, as Richard Bosworth phrased it in the title of one of his books, the Least of the Great Powers and was also regarded, by allies and potential enemies alike, as somewhat lukewarm in its adherence to the Triple Alliance.

Because none of the Great Powers desired any great upset in the equilibrium that their alliance system precariously maintained, the Italian decision to go to war against the Ottoman Empire created a situation of great diplomatic delicacy. They had to try to find a middle way that neither encouraged nor discouraged Italian ambitions for fear of driving them into the arms of the opposing bloc. On the other hand, and with the Eastern Question very much in mind, a somewhat similar policy towards the Ottomans was also necessary. Thus one of the most important effects of the Italo-Ottoman War was upon European Great Power politics.

It was an unusual war in other respects too, inasmuch as in order to conduct it at all Italy had to confine its military and naval activities to areas where they would neither cause a widening of the conflict, nor conflict with the interests of the Great Powers. This led to most of the fighting being restricted to North Africa, though it did widen as time went on to much international concern. This occurred because the fighting in the Tripoli vilayet became, as it would be today termed, asymmetrical in character when the Ottoman military were forced to resort to a guerrilla strategy. Due to the nature of the terrain, and the training and capabilities of the Italian military, this led to tactical and operational deadlock and the subsequent paralysis of Italian strategy. Basically put, the invaders were largely compelled to remain within their coastal enclaves, protected by extensive field works and covered by the guns of their fleet.

The defenders, Ottoman regulars and their Arab and Berber co-fighters, were not equipped to assault such works, and the strategy of the Ottoman commanders was, by default, mainly based around attempting to lure the Italians out so that they could be attacked in the desert.

Consequently, the Italians were forced into attempts to bring the Ottoman Empire to terms by applying pressure in other areas, thus bringing them into potential conflict with the Great Powers. It was then no easy war for either the Italian military, or the Italian Government, to wage with any seeming degree of success, and what was foreseen as a short and victorious war of easy conquest turned into a protracted and bitter conflict that endured for just over a year.

This book is the story of that conflict, which has been almost forgotten given the events that followed it in short order, particularly the First World, or Great, War. Indeed, though there are several works in Italian and Turkish in print that cover the subject, there is nothing in English that deals with it either holistically or in any great depth. This work is an effort to remedy this deficiency, and indeed the conflict has many interesting facets, not least the introduction of aircraft into combat situations for the first time and the deployment of armoured vehicles similarly. It was a war where one side, Italy, held and maintained naval supremacy, though the existence of an Ottoman fleet in being exercised the Regia Marina to the extent that attempts were made to penetrate the Dardanelles and sink it. The difficulties encountered in so doing were lessons that other navies might have studied with profit.

It was also a campaign that was generally considered to have done nothing to bolster Italian military prestige. This judgement is however rather unfair, inasmuch as the Italian Army did what the politicians asked of it, and no army could have done much more given the state of technology at the time. It was, as has been stated, a war fought for jingoistic or social-imperialistic purposes and was in any event totally unnecessary. The Italian government, or more precisely Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti and Foreign Minister Marquis Antonio di San Giuliano, could have had virtually all they wanted without going to war, but needed a smashing victory in order to placate the ascendant nationalist right-wing politicians and newspapers whose prisoners they had become. The conflict turned out very differently however, and whilst retrospectively it seems incredible that any sensible government would embark on a military venture with so much wishful thinking as to the likely reaction and outcome, it is perhaps the case that they were not so uncommon after all. Recent history teaches us that at least.

Next page