Contents

For David and Martin

Fredric Jameson, The Modernist Papers, London and New York: Verso, 2007, p.ix.

Theocritus, The Idylls (trans. Robert Wells), Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988, p.107.

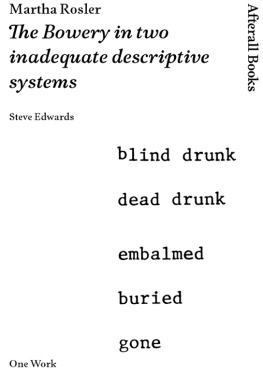

For the complicated history of its making and exhibition see Martha Gever, An Interview with Martha Rosler, Afterimage, vol.9, no.3, p.15; and Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, A Conversation with Martha Rosler, in Catherine de Zegher (ed.), Martha Rosler: Positions in the Life World, Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press, 1998, p.44. This volume contains a bibliography and list of the artists writings and works up to 1990.

See Martha Rosler, 3 Works, Halifax, Nova Scotia: The Press of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1981. In 2006, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication, NSCAD republished it, with the addition of a text by Rosler titled Afterword: A History (pp.94103). Rosler suggests here that she wrote In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography) at the instigation of Benjamin Buchloh, who felt viewers would not understand a photographic practice that eschewed originality in favour of stylistic repetition.

An earlier version of Sekulas essay Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation) accompanied Fred Lonidiers Health and Safety Game and Phel Steinmetzs Somebodys Making a Mistake (exh. cat.), Long Beach, CA: Long Beach Museum of Art, 1976. It was revised with the same title in Massachusetts Review, vol.19, no.4, 1978, pp.85983, and this version was republished in Terry Dennett, David Evans, Sylvia Gohl and Jo Spence (ed.), Photography/Politics: One, London: Photography Workshop, 1979, pp.17185. It has subsequently appeared in a number of publications, including collections of Sekulas essays. All quotations in this book refer to the version printed in Photography/Politics: One.

Brian Connell, Steve Buck, Adele Shaules and Marge Dean are also mentioned in various sources.

In one of the best critical periodisations of recent times, Gail Day coined the term the long 1980s. See G. Day, Dialectical Passions: Negation in Post-War Art Theory, New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

A. Sekula, Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary, op. cit., p.175.

The 2006 reprint is made from new prints. See M. Rosler, 3 Works, Halifax: The Press of Nova Scotia College, 2006.

F. Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, London and New York: Verso, 1991, p.78.

M. Rosler, In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography), 3 Works, op. cit., p.71.

One reason for this antipathy to Ruscha was his interest in Marcel Duchamp. Rosler and her comrades were interested in found meaning and the readymade, but the aristocratic dandyism associated with Duchamp was undoubtedly a turn-off. There are critical references to dandyism as a form of elite detachment throughout the work of Rosler.

M. Rosler, Afterword: A History, 3 Works, op. cit., 2006, p.95.

For ease of comprehension, I have assigned a number to each text/image pairing, or element, in a consecutive sequence from top left to bottom right. This is not unproblematic and prejudices the viewer of The Bowery to read as Westerners read a book, from left to right, continuing at the next line. Other associative patterns are possible; for instance, the work could be viewed as vertical columns, rather than horizontal rows. However, the advantage of the numbered sequence is that it is applicable to both the gallery and book versions of The Bowery. It was initially shown unframed, until one museum tried to nail it to the wall. (Email from the artist, 2 November 2010.) This version is in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. I cannot account for this oddity. The pairings of image and text reproduced sometimes depart from the standard version. The image/text juxtaposition on the back cover of 3 Works combines the photograph from element 12 with the text from element 11. This is strange, because this combination detaches the image of the bank faade from the word grouping for surfaces, with which it seems to belong. Sometimes, this alternate pairing is reproduced in survey books. The version with the variant ending appears in Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art (London: Phaidon, 2002, p.154); and David Campany, Art and Photography (London: Phaidon, 2007, p.114).

From the Greek ek (out, ex-) and phrazo (I explain), ekphrasis is a rhetorical category for presenting or recalling images in words, so that they appear present to the listener. Homers description of Achilless shield in Book 18 of the Iliad is often seen as the beginning of the ekphrastic tradition. See Ruth Webb, Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion in Ancient Rhetorical Theory and Practice, Farnham: Ashgate, 2009; W.J.T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Elizabeth A. MacGregor and Sabine Breitwieser, Foreword, in C. de Zegher (ed.), Positions in the Lifeworld, op. cit., p.9.

Recent exhibitions include Open Systems: Rethinking Art c.1970 (Tate Modern, London, 2005) and documenta 12 (Kassel, 2007). At the time of writing, it is on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Craig Owens, The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism, in Hal Foster (ed.), Postmodern Culture, London: Pluto Press, 1985, p.68.

Ibid., p.69.

Thomas Crow, Unwritten Histories of Conceptual Art: Against Visual Culture, Modern Art in the Common Culture, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996, p.217.

Brandon Taylor, The Art of Today, London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1995, p.24. The comment on refusal is from Roslers essay In, Around, and Afterthoughts, op. cit., p.79.

Laura Cottingham, The Inadequacy of Seeing and Believing: The Art of Martha Rosler, in C. de Zegher (ed.), Inside the Visible: An Elliptical Traverse of 20th Century Art (exh. cat.), Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press, 1994, p.161.

See B.H.D. Buchloh, A Conversation with Martha Rosler, op. cit.

M. Rosler, In, Around, and Afterthoughts, op. cit., p.78.

C. Owens, The Discourse of Others, op. cit., pp.6970.

Rosler in B.H.D. Buchloh, A Conversation with Martha Rosler, op. cit., pp.3942.

A. Sekula, Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary, op. cit., p.175. Rosler called it a walk down the Bowery; see M. Rosler, In, Around, and Afterthoughts, op. cit., p.79. Sekula notes there are 24 photographs and a near equal number of texts. The reverse is true, but this is an interesting slip that registers something significant about the viewers expectations with regard to the balance between texts and images in The Bowery.

A. Sekula, Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary, op. cit., p.175.

Rosler notes The Bowery is not a work of defiant antihumanism, and this is important. M. Rosler, In, Around, and Afterthoughts, op. cit., p.79.

See M. Rosler, 3 Works, op. cit., 2006, p.96.

A. Sekula, Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary, op. cit., p.175.

M. Rosler, Afterword: A History, op. cit., p.96.

The Bowery is discussed in these terms in B.H.D. Buchloh, Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary Art, Artforum, vol.21, no.1, September 1982, pp.4356.

Next page