All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016.

INTRODUCTION

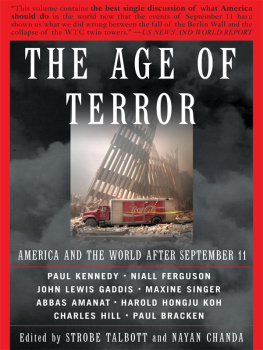

M OMENTOUS EVENT HAVE a way of connecting individuals both to history and to one another. So it was on September 11. Even before more than 4,000 people died in less than two hours, there were farewell messages from the sky. In their last minutes, doomed passengers used cell phones to reach loved ones. A short time later, office workers trapped high in the burning towers called spouses, children, parents. Never had so many had the means to say good-bye.

During the hours afterward, the survivors scrambled to make contact with family and friends. Are you all right? they asked.

After the intimate connections came the communal onesin religious observances, town meetings, hastily arranged get-togethers in places of work, television and radio call-in shows. There were gatherings at schools and colleges across the United States. At Yale, where six of the authors of the following essays teach, the first assembly was pastoral, reserved for prayer and moments of silence.

As the enormity of it all began to sink in, the question hanging in the air was, Were we all right?

We meant more than Americans. The list of the victims in New York was as cosmopolitan as the city itself. There were citizens of 62 countries, including 250 Indians, 200 Pakistanis, 200 Britons, 55 Australians and 23 Japanese. On every continent, places of worship held memorial services; parks and squares filled with people demonstrating their sympathy; thousands lined up at U.S. embassies and consulates to sign condolence books. There were two large candlelight vigils in Iran. Americans were inundated with phone calls, emails and letters with messages of empathy from abroad.

Partly, no doubt, because of this outpouring of compassion, support and solidarity from around the world, the isolationist nerve in the American body politic barely twitched. There was a surge of combative patriotism, but it left room for variations on the theme were all in this thingtogether. In his address to the joint houses of Congress, President Bush made a point of internationalizing the nations sense of outrage and resolve: This is the worlds fight. This is civilizations fight.

In the weeks that followed, students everywhere wanted to keep getting together, not just for solace and reflection but for inquiry into what had happened, who had done it, why, what it meant, and what the U.S. and others should do about it. What theyd witnessed, many of them said, cried out for context.

Teach-in, the phrase from the sixties and seventies, didnt quite apply, since the teachers didnt have many answers, or even all the right questions. They knew it. September 11, like the commandeered planes themselves, had come out of the blue. Just as the U.S. government was caught off guard, so the citizenry was unprepared, emotionally and intellectually.

In discussions around the Yale campusin classrooms, common rooms and dining halls, at kitchen tables in faculty homes, on lawns in the sunshine throughout an especially mild and glorious Indian summera number of us noted a humbling irony: the more time wed spent in the old world and the better we thought we understood its organizing principles, the less ready we were for the new one. Not surprisingly, therefore, it was often from the studentswho had just experienced the first great public trauma of their livesthat we heard an especially useful insight, a fresh intuition or a clarifying formulation of one of the many ethical, political and strategic tests that lay ahead.

Suddenly, familiar terms and concepts were inadequate, starting with the word terrorism itself. The dictionary defines it as violence, particularly against civilians, carried out for a political purpose. September 11 certainly qualified. But Americas earlier encounters with terrorism neither anticipated nor encompassed this new manifestation. U.S. citizens had been casualties before, but usually when they were far from homein a military barracks in Lebanon in 1983 or Saudi Arabia in 1996, on a cruise ship in the Mediterranean in 1985, in a jumbo jet over Scotland in 1988, or in two U.S. embassies in East Africa in 1998. This time, the prey were not just on American soil but inside the iconic headquarters of American prosperity, security and strength.

September 11 left nearly five times as many Americans dead as all terrorist incidents of the previous three decades combined. The carnage was nearly thirty times greater than what Timothy McVeigh, a homegrown madman, had inflicted on Oklahoma City in 1995, and about double what three hundred Japanese bombers left in their wake at Pearl Harbor. Commentators instantly evoked that other bolt-from-the-blue raid, sixty years before, as the closest thing to a precedent. But there really was none. This was something new under the sun.

The attacks were immediately declared acts of war. Yet that word, too, seemed not quite to fit. Wed always thought of war either as civil strife within a nation or systematic violence committed by one state or alliance against another. War, however brutal and capricious, had its own rules and made its own accommodations, even in the midst of mayhem, with the human instinct for self-preservation. While risking death and meting it out to others, combatants hoped to survive and savor victory. The cold war never turned hot because the superpowers agreed on one thing if nothing elsethe overarching imperative of avoiding Armageddon.

This new enemy was different. Osama bin Ladens organization, al Qaeda, flew no flagit was the ultimate NGOand his warriors seemed inspired rather than deterred by the prospect of their own fiery deaths.

What was it, exactly, that inspired them? Part of the answer, undeniably, had something to do with one of the worlds great religions and the spiritual home of several great civilizations. The pilots, whose names and mug shots people all over the world came to know well, were driven not just by anger and hatred but by a grotesque yet, for them at least, compelling version of the Muslim faith. Many Americans who had never seen a copy of the Koran, much less read a single passage, were riveted by the last will and testament of Mohammed Atta, who was probably at the controls of American Flight 11 when it slammed into the north tower of the World Trade Center at 8:45 a.m. That document was perhaps deliberately left behind in a piece of luggage so that it could be excerpted in newspapers all over the world. It was filled with exhortations to martyrdom and promises of divine reward for the eighteen other hijackers. Those for whom Attas letter was an introduction to the teachings of the Prophet went from knowing little about Islam to thinking they now knew quite a bit.