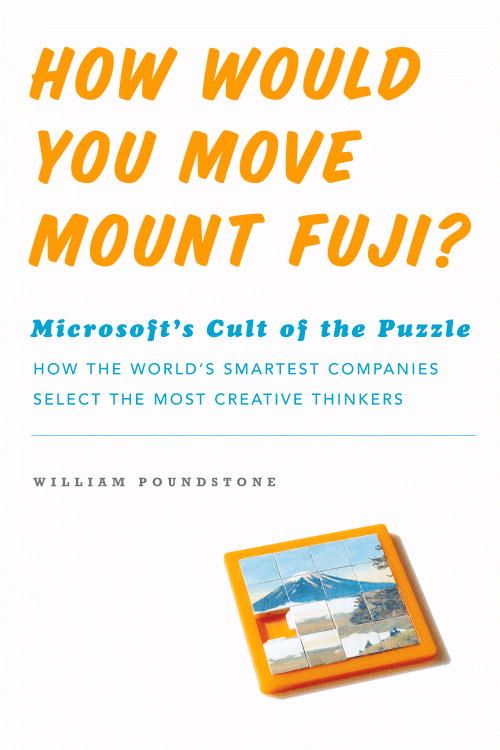

Also by William Poundstone

BIG SECRETS

THE RECURSIVE UNIVERSE

BIGGER SECRETS

LABYRINTHS OF REASON

THE ULTIMATE

PRISONERS DILEMMA

BIGGEST SECRETS

CARL SAGAN: A LIFE IN THE COSMOS

To my father

Contents

Like any other value, puzzle-solving abilty proves equivocal in application.... But the behavior of a community which makes it preeminent will be very different from that of one which does not.

Thomas Kuhn

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

As, in a Chinese puzzle, many pieces are hard to place, so there are some unfortunate fellows who can never slip into their proper angles, and thus the whole puzzle becomes a puzzle indeed, which is the precise condition of the greatest puzzle in the world this man-of-war world itself.

Herman Melville

White-Jacket

To understand that cleverness can lead to stupidity is to be close to the ways of Heaven.

Huang Binhong

Insects and Flowers

One The Impossible Question

In August 1957 William Shockley was recruiting staff for his Palo Alto, California, start-up, Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory. Shockley had been part of the Bell Labs team that invented the transistor. He had quit his job and come west to start his own company, telling people his goal was to make a million dollars. Everyone thought he was crazy. Shockley knew he wasnt. Unlike a lot of the people at Bell Labs, he knew the transistor was going to be big.

Shockley had an idea about how to make transistors cheaply. He was going to fabricate them out of silicon. He had come to this valley, south of San Francisco, to start production. He felt like he was on the cusp of history, in the right place at the right time. All that he needed was the right people. Shockley was leaving nothing to chance.

Todays interview was Jim Gibbons. He was a young guy, early twenties. He already had a Stanford Ph.D. He had studied at Cambridge too on a Fulbright scholarship hed won.

Gibbons was sitting in front of him right now, in Shockleys Quonset hut office. Shockley picked up his stopwatch.

Theres a tennis tournament with one hundred twenty-seven players, Shockley began, in measured tones. Youve got one hundred twenty-six people paired off in sixty-three matches, plus one unpaired player as a bye. In the next round, there are sixty-four players and thirty-two matches. How many matches, total, does it take to determine a winner?

Shockley started the stopwatch.

The hand had not gone far when Gibbons replied: One hundred twenty-six.

How did you do that? Shockley wanted to know. Have you heard this before?

Gibbons explained simply that it takes one match to eliminate one player. One hundred twenty-six players have to be eliminated to leave one winner. Therefore, there have to be 126 matches.

Shockley almost threw a tantrum. That was how he would have solved the problem, he told Gibbons. Gibbons had the distinct impression that Shockley did not care for other people using his method.

Shockley posed the next puzzle and clicked the stopwatch again. This one was harder for Gibbons. He thought a long time without answering. He noticed that, with each passing second, the rooms atmosphere grew less tense. Shockley, seething at the previous answer, now relaxed like a man sinking into a hot bath. Finally, Shockley clicked off the stopwatch and said that Gibbons had already taken twice the lab average time to answer the question. He reported this with charitable satisfaction. Gibbons was hired.

Find the Heavy Billiard Ball...

Fast-forward forty years in time only a few miles in space from long-since-defunct Shockley Semiconductor to a much-changed Silicon Valley. Transistors etched onto silicon chips were as big as Shockley imagined. Software was even bigger. Stanford was having a career fair, and one of the most popular companies in attendance was the Microsoft Corporation. With the 1990s dot-com boom and bull market in full swing, Microsoft was famous as a place where employees of no particular distinction could make $1 million before their thirtieth birthday. Grad student Gene McKenna signed up for an interview with Microsofts recruiter.

Suppose you had eight billiard balls, the recruiter began. One of them is slightly heavier, but the only way to tell is by putting it on a scale against the others. Whats the fewest number of times youd have to use the scale to find the heavier ball?

McKenna began reasoning aloud. Everything he said was sensible, but somehow nothing seemed to impress the recruiter. With hinting and prodding, McKenna came up with a billiard-ball-weighing scheme that was marginally acceptable to the Microsoft guy. The answer was two.

Now, imagine Microsoft wanted to get into the appliance business, the recruiter then said. Suppose we wanted to run a microwave oven from the computer. What software would you write to do this?

Why would you want to do that? asked McKenna. I dont want to go to my refrigerator, get out some food, put it in the microwave, and then run to my computer to start it!

Well, the microwave could still have buttons on it too.

So why do I want to run it from my computer?

Well maybe you could make it programmable? For example, you could call your computer from work and have it start cooking your turkey.

But wouldnt my turkey, asked McKenna, or any other food, go bad sitting in the microwave while Im at work? I could put a frozen turkey in, but then it would drip water everywhere.

What other options could the microwave have? the recruiter asked. Pause. For example, you could use the computer to download and exchange recipes.

You can do that now. Why does Microsoft want to bother with connecting the computer to the microwave?

Well lets not worry about that. Just assume that Microsoft has decided this. Its your job to think up uses for it.

McKenna thought in silence.

Now maybe the recipes could be very complex, the recruiter said. Like, Cook food at seven hundred watts for two minutes, then at three hundred watts for two more minutes, but dont let the temperature get above three hundred degrees.

Well there is probably a small niche of people who would really love that, but most people cant program their VCR.

The Microsoft recruiter extended his hand. Well, it was nice to meet you, Gene. Good luck with your job search.

Yeah, said McKenna. Thanks.

The Impossible Question

Logic puzzles, riddles, hypothetical questions, and trick questions have a long tradition in computer-industry interviews. This is an expression of the start-up mentality in which every employee is expected to be a highly logical and motivated innovator, working seventy-hour weeks if need be to ship a product. It reflects the belief that the high-technology industries are different from the old economy: less stable, less certain, faster changing. The high-technology employee must be able to question assumptions and see things from novel perspectives. Puzzles and riddles (so the argument goes) test that ability.

In recent years, the chasm between high technology and old economy has narrowed. The uncertainties of a wired, ever-shifting global marketplace are imposing a start-up mentality throughout the corporate and professional world. That world is now adopting the peculiar style of interviewing that was formerly associated with lean, hungry technology companies. Puzzle-laden job interviews have infiltrated the Fortune 500 and the rust belt; law firms, banks, consulting firms, and the insurance industry; airlines, media, advertising, and even the armed forces. Brainteaser interview questions are reported from Italy, Russia, and India. Like it or not, puzzles and riddles are a hot new trend in hiring.